Bangladesh Hindu Displacement: From Partition to Marichjhapi Part-II

A Journey of Displacement of Bangladesh Hindu

We have covered the broad contours of incident Bangladesh Hindu Killings in Marichjhapi in the previous blog titled: “Bangladesh Hindu Killings Marichjhapi: The Untold Story Part-I”. This blog, “Bangladesh Hindu Displacement: From Partition to Marichjhapi Part-II” covers what forced the Bangladesh Hindus become targets of bullet of Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee Government.

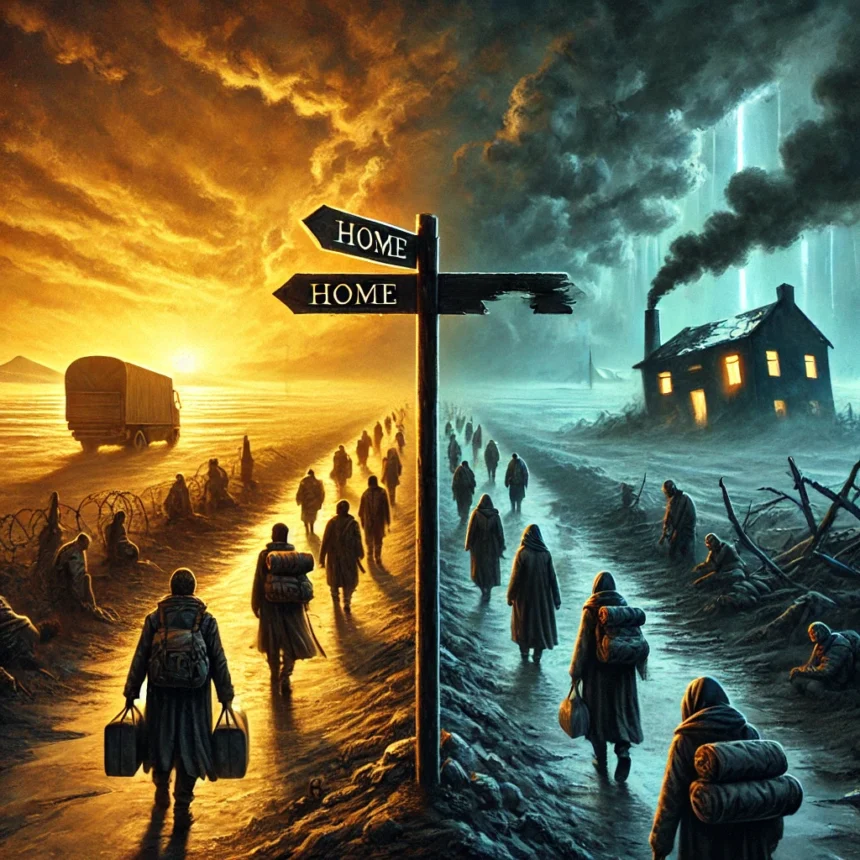

As we turn to the next chapter in this tragic saga that occurred on 31 January 1979, we trace the journey that led thousands of Bangladesh Hindu refugees to Marichjhapi. Fleeing relentless persecution, the Bangladesh Hindu endured displacement, broken promises, and harsh resettlement conditions, only to face betrayal in a land they hoped would offer refuge. This blog uncovers the decades of systemic neglect and shifting political priorities that culminated in their violent suppression, exposing the forces that turned them from victims of persecution into targets of state brutality.

The Fallout of Partition: A Fractured Homeland

When the British carved India into two nations in 1947, the Partition didn’t just draw lines on a map—it shattered lives. East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) became a hostile land for millions of Hindus caught in communal violence. Overnight, families fled across the new border to West Bengal, clutching what little they could carry. The initial wave—upper- and middle-class Bangladesh Hindus—found ways to rebuild, leveraging education and networks in Kolkata and beyond. But for the poorer, rural Bangladesh Hindus, especially Dalit communities like the Namashudras, the story was starkly different.

The Namashudras, once a thriving agricultural caste in East Bengal, faced relentless persecution post-Partition. Their homes were torched, lands seized, and lives threatened by neighbors turned foes in a newly Muslim-majority region. Worse still, extremist elements, remembering their actions in Noakhali and adjoining areas, resumed their brutal tactics—Hindu women were abducted, assaulted, and forcibly converted in a continuation of the terror that had driven so many out in 1946. By 1951, East Pakistan’s Hindu population had plummeted from 22% to around 18%, with an estimated 5 million crossing into India over the next decade.

West Bengal, their cultural and linguistic homeland, seemed a natural refuge. Yet, the state—already strained by population and poverty—offered little welcome. For these lower-caste refugees, the promise of safety morphed into a struggle for survival, setting the stage for decades of Bangladesh Hindu Displacement.

Dandakaranya: A Promise of Resettlement Turns to Dust

By the 1950s and 1960s, India’s government faced a refugee crisis it couldn’t ignore. West Bengal’s resources buckled under the influx, and political pressure mounted to decongest the state.

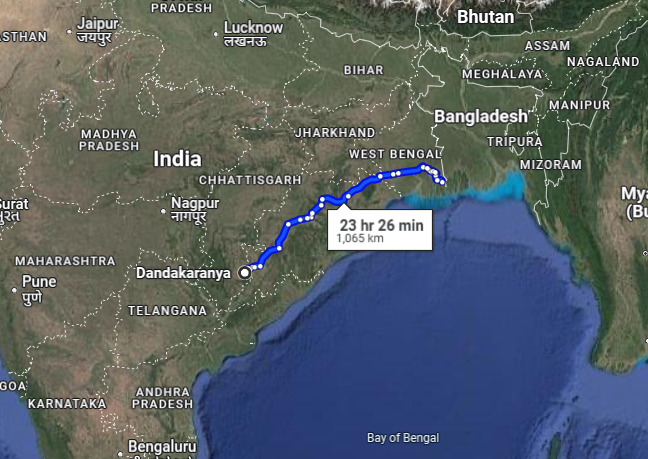

The solution? Relocate the “excess” refugees—mostly Dalits and rural poor—to Dandakaranya, a sprawling, arid region across modern-day Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and Andhra Pradesh. Launched in 1958, the Dandakaranya Development Authority promised a fresh start: land, homes, and a chance to thrive.

Reality, however, was a cruel mirage. Dandakaranya’s rocky soil and scant water mocked the Namashudras’ farming heritage. Unlike Bengal’s fertile deltas, this land resisted cultivation, yielding little beyond frustration. Families were dumped in isolated camps, handed meager rations, and left to fend for themselves in a landscape alien to their skills and culture. Promises of infrastructure—schools, wells, roads—faded into bureaucratic neglect. By the 1970s, after the Bangladesh Liberation War swelled refugee numbers again, the camps became a purgatory of disease, hunger, and despair. The camps became a purgatory of disease, hunger, and despair, worsened by the Pakistan Army’s greater brutality toward Bangladesh Hindus than Muslims.

Survivors recall the hopelessness. “We were fishermen and farmers,” one refugee later told journalist Deep Halder. “They gave us stones and told us to grow rice.” Over 20 years, some 40,000 families were sent to Dandakaranya, but nearly half abandoned it, trickling back to West Bengal or clinging to whispers of better prospects. The scheme’s failure wasn’t just logistical—it was a betrayal of trust, a government shrugging off its most vulnerable. Yet, amid this desolation, a flicker of hope emerged in 1977, igniting the path to Marichjhapi.

From One Exodus to Another: The Shift from Dandakaranya to Marichjhapi

For the Bangladesh Hindu refugees trapped in Dandakaranya’s unforgiving terrain, West Bengal remained the only place they could truly call home. Their hopes were reignited in 1977 when the Left Front, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)), came to power, vocally criticizing the previous government’s neglect of the refugees. Left leaders, particularly from the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP), assured those stranded in Dandakaranya that they would be welcomed back and rehabilitated in Bengal. Encouraged by these promises, thousands sold whatever little they had and embarked on yet another exodus—this time toward Marichjhapi. With no resources for proper transport, many walked or traveled over a thousand kilometers, enduring hunger, exhaustion, and uncertainty, clinging to the hope that Bengal would finally offer them refuge.

However, once in power, the Left Front faced immense pressure from its settled voter base, environmental regulations, and political calculations. The very refugees they had invited back were soon labeled “illegal encroachers” and a “burden” on the state. The party’s reversal was swift and brutal, culminating in the events of January 31, 1979, when the very government that had given them hope turned its guns on them. What had begun as a journey of return became yet another betrayal, marking Marichjhapi as the site of one of independent India’s most tragic episodes of state violence.

The Left Front’s Broken Promises: A Glimmer Snuffed Out

In June 1977, the Left Front, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)), swept to power in West Bengal, ending decades of Congress rule. For the refugees languishing in Dandakaranya, the victory was a lifeline. The Left had long championed the downtrodden, railing against the central government’s neglect of Bangladesh refugees. Leaders like Ram Chatterjee of the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP), a Left Front ally, explicitly urged the Dandakaranya settlers to return to Bengal, promising rehabilitation in their cultural homeland.

The rhetoric was intoxicating. “Come back to Bengal,” the Left proclaimed, tapping into the refugees’ longing for familiar soil and language. By late 1977, thousands, displaced by the Bangladesh Hindu Displacement, heeded the call, selling scraps of belongings to fund the trek back. Among them were the Namashudras and other Dalits, who saw the Left Front as saviors after years of abandonment. Estimates suggest 15,000 to 40,000 made the journey, converging on the Sundarbans—an untamed delta of rivers and mangroves—where they claimed Marichjhapi, an uninhabited island.

For a fleeting moment, Marichjhapi shimmered with possibility. The refugees renamed it “Netaji Nagar” after Subhas Chandra Bose, a freedom struggle icon, and set to work. They built homes from mud and thatch, dug fisheries, and opened schools, crafting a community from resilience alone. By early 1978, markets buzzed, and children studied under makeshift roofs—a testament to their defiance of the odds. “We thought we’d finally found our place,” a survivor recalled. But this dream was a mirage, soon to be crushed by the very government that had beckoned them.

The Left Front’s promise unraveled fast. Once in power, the CPI(M) faced pressure from local voters and ecological concerns—the Sundarbans was a protected tiger reserve. By mid-1978, the narrative shifted: the refugees were “illegal encroachers,” a burden West Bengal couldn’t bear. The same leaders who’d invited them now declared them a “national problem” to be dispersed.

This betrayal was not just a practical decision but a calculated political maneuver, possibly to appease settled constituencies at the expense of refugee rights—an issue deeply intertwined with the broader context of Bangladesh Hindu Displacement. What began as a beacon of hope dimmed into a prelude to horror, setting the stage for one of the darkest chapters in post-Partition history. Was this to appease settled constituencies over refugee rights? We will discover this in the next Blog of the series: Politics of the Massacre. What began as a beacon of hope dimmed into a prelude to horror.

Reflections on Bangladesh Hindu and Unfolding Tragedy

From the chaos of Partition to the broken dreams of Dandakaranya, the refugees’ journey to Marichjhapi was one of relentless struggle for belonging—only to be met with betrayal. The Left Front, once their beacon of hope, turned into the architect of their downfall, paving the way for the violent crackdown of 1979. This was not merely a failed policy but a stark reflection of systemic neglect, political opportunism, and the shifting tides of power.

Marichjhapi was never just an island; it was the embodiment of decades of persecution and the Bangladesh Hindu displacement.

As we examine its tragic end, we must ask—was this massacre inevitable, or was it orchestrated? The next blog, “Politics of the Massacre,” dissects the political forces that sealed the fate of the refugees and turned their struggle into one of the most chilling betrayals in independent India’s history.

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Glossary of Terms:

- Bangladesh Hindu Killings: Refers to the persecution and violence faced by Hindus in Bangladesh, particularly during and after the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War.

- Marichjhapi massacre: A violent incident that occurred on January 31, 1979, in which thousands of Bengali Hindu refugees were killed or displaced by the West Bengal government.

- Partition of India: The division of British India into India and Pakistan in 1947, resulting in one of the largest mass migrations in history.

- Dalits: A term referring to the lowest castes in the traditional Indian caste system, often facing social and economic discrimination.

- Namashudras: A Dalit community from East Bengal (now Bangladesh), who faced significant persecution and displacement during and after the Partition.

- Dandakaranya: A region in central India where the Indian government resettled thousands of Bengali Hindu refugees from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in the 1950s and 1960s.

- Left Front: A political alliance in West Bengal, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)), which came to power in 1977.

- CPI(M): The Communist Party of India (Marxist), a left-wing political party in India.

- RSP: The Revolutionary Socialist Party, a left-wing political party in India and an ally of the CPI(M) in the Left Front.

- Sundarbans: A mangrove forest in the Ganges River Delta, spanning across West Bengal and Bangladesh.

- Netaji Nagar: The name given to Marichjhapi island by the Bengali Hindu refugees, after Subhas Chandra Bose, a freedom struggle icon.

Past Blogs of Series

Later parts of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/bangladesh-hindu-killings-politics-of-massacre-part-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/bangladesh-hindu-massacre-persecution-past-and-present-part-iv/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/bangladesh-hindu-killings-kumirmari-a-sky-of-hope-lost-part-v/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/bangladesh-hindu-persecution-cost-of-tolerance-and-unity-call-part-vi/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/hindu-persecution-in-west-bengal-the-struggles-of-the-minority/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/attacks-on-hindus-a-threat-to-identity/

Follow us:

- English YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@Hinduofficialstation

- Hindi YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@HinduinfopediaIn

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

Top Hashtags: #MarichjhapiMassacre #BengaliHinduRefugees #PartitionSurvivors #ForcedMigration #DandakaranyaExodus

Leave a Reply