East India Company Treaty of Allahabad 1765: The Legal Foundation of British Empire

Part II: Study of East India Company and Foreign rule in Bharat

The East India Company Treaty That Changed Bharat’s Destiny

On August 12, 1765, in the city of Allahabad, a weakened Mughal Emperor signed away the economic sovereignty of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa to a foreign trading company. The Treaty of Allahabad was signed on 16 August 1765, between the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and Robert Clive, of the East India Company, in the aftermath of the Battle of Buxar of 22 October 1764. This seemingly technical agreement would prove to be the legal foundation upon which the British Empire in India was built—transforming merchants into tax collectors and commercial ambition into imperial authority.

The East India Company Treaty of Allahabad was not merely a diplomatic document; it was the constitutional moment when corporate power replaced sovereign authority, when profit-seeking merchants gained the right to extract wealth from one of the world’s richest territories, and when the systematic impoverishment of Bharat received legal sanction. This blog examines the treaty’s provisions, the dual system it created, and the immediate consequences that would echo through centuries.

The Battle of Buxar: Setting the Stage for the East India Company Treaty

To understand the Treaty of Allahabad, we must first grasp the military and political context that made it possible. The Battle of Buxar (1764) was not just another military engagement—it was the moment when the East India Company defeated the combined forces of the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, the Nawab of Awadh Shuja-ud-Daulah, and the deposed Nawab of Bengal Mir Qasim.

It mirrored the fractured Islamic polity that had emerged after Aurangzeb’s tyrannical reign, when oppression and over-centralization left the empire hollow. Centuries of discriminatory taxation, temple destruction, and religious bias had alienated the Hindu majority, who no longer saw the Mughal state as their own. This deep-seated resentment ensured that, when crisis came, the empire found few willing defenders among its subjects. The Mughal Emperor brought the legitimacy of imperial authority. The Nawab of Awadh commanded substantial military resources. Mir Qasim sought to reclaim Bengal from Company control. Together, they should have expelled the British traders from Indian soil — but the moral fabric that could have united them had long been torn apart.

Years earlier, Ahmad Shah Abdali’s invasions and Mughal weakness had already signaled the disintegration of centralized authority.

Yet the Company’s victory at Buxar was decisive and devastating. The battle revealed the complete collapse of traditional Islamic military and political structures—structures that had been systematically weakened by decades of Hindu resistance led by Shivaji and the Marathas. The Company’s disciplined sepoy army, trained in European methods and commanded by British officers, proved superior to much larger traditional forces plagued by divided command, obsolete tactics, and corrupt leadership.

More significantly, Buxar demonstrated that the Mughal Emperor himself—the symbolic apex of Islamic authority in India—could be militarily defeated by a foreign trading company. This psychological blow would prove as important as the military victory itself.

Shah Alam II: The Emperor Without an Empire

Shah Alam II was the nominal Mughal emperor of India from 1759 to 1806. Understanding Shah Alam II’s position is crucial to grasping the tragedy and significance of the Treaty of Allahabad. He was not a strong emperor making strategic concessions; he was a desperate ruler clinging to the last vestiges of imperial dignity.

Shah Alam’s reign began in crisis. He was forced to flee Delhi in 1758 by the minister Imad al-Mulk, who kept the emperor a virtual prisoner. When his father, Emperor Alamgir II, was assassinated by his own minister, Shah Alam found himself an emperor without a capital, wandering through his own domains seeking protection from regional powers.

The Battle of Buxar left him defeated and dependent on the very Company that had just crushed his forces. His authority had weakened so much that a Persian saying emerged: “Sultanat-e-Shah Alam, Az Dilli ta Palam,” meaning his empire extended only from Delhi to Palam (a distance of mere miles).

This was the man who would sign the East India Company Treaty of Allahabad—not from a position of strength, but from desperate necessity. The British, recognizing that they were not yet strong enough to openly claim sovereignty, kept Shah Alam as a puppet till his death in 1805. The treaty would formalize this puppet relationship, giving the Company real power while allowing the Emperor to retain hollow dignity.

The East India Company Treaty Provisions: Power Behind Legal Language

The East India Company Treaty of Allahabad contained several key provisions that collectively transferred real power to the East India Company while maintaining the fiction of Mughal sovereignty:

1. The Diwani Rights

The treaty’s most significant provision was the grant of Diwani rights, legitimizing what the Islamic Jazia-style taxation had once enforced through religion — now transformed into corporate economics. Based on the terms of the agreement, Alam granted the East India Company Diwani rights, or the right to collect taxes on behalf of the Emperor from the eastern province of Bengal-Bihar-Orissa.

In Mughal administrative terminology, the Diwan was the revenue minister responsible for collecting taxes and managing financial affairs. By granting Diwani rights to the Company, Shah Alam II essentially appointed a foreign trading corporation as the revenue administrator for three of the empire’s wealthiest provinces.

These rights allowed the company to collect revenue directly from the people of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This was not merely taxation—it was access to the entire economic output of one of the world’s most prosperous regions. Bengal alone generated revenues of approximately £3 million annually (equivalent to hundreds of millions in today’s currency), while its textile exports, agricultural production, and commercial activities made it the jewel of the Mughal Empire.

The significance of this provision cannot be overstated. The Company now had legal authority to extract wealth directly from millions of people, funded by the very populations they would increasingly impoverish. This created a self-perpetuating cycle: revenues from Bengal funded Company military expansion, which in turn enabled the conquest of more territory, generating more revenues.

2. The Annual Payment

In exchange for these revenue rights, the Company agreed to pay the Mughal Emperor an annual tribute of 26 lakh rupees (approximately £260,000). This payment served multiple purposes. It maintained the legal fiction that the Company operated under imperial authority, providing a thin veneer of legitimacy to what was essentially economic conquest.

More cynically, this payment was a bargain. The Company would collect revenues exceeding £3 million while paying the Emperor less than one-tenth of that amount. The Emperor received symbolic recognition while the Company gained real wealth—a perfect illustration of how the East India Company treaty favored British interests while exploiting the weakness of Mughal authority.

3. Protection and Alliance

The treaty also stipulated that Shah Alam II would reside at Allahabad under Company protection — much like later Indian rulers reduced to ceremonial positions under British control, a humiliation reminiscent of what Guru Arjan Dev Ji and Guru Tegh Bahadur had resisted centuries earlier in spiritual form.” This provision transformed the Emperor from a sovereign ruler into a protected—essentially, a prisoner with imperial titles. The Company now controlled where the Emperor lived, whom he met, and how he exercised whatever authority remained to him.

Additionally, the East India Company treaty formalized a military alliance between the Company and the Emperor against common enemies. In practice, this meant the Company could use the Emperor’s name and authority to legitimize their military campaigns while the Emperor had no real say in Company military decisions.

4. Territory for the Nawab of Awadh

The treaty also addressed Shuja-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Awadh, who had allied with Shah Alam II against the Company. Defeated at Buxar, he now had to pay a war indemnity and cede territories to the Company. In return, the Company guaranteed his position as Nawab and promised protection—effectively converting Awadh into a buffer state dependent on British support.

This pattern would repeat throughout India: defeat in battle led to treaties that converted sovereign rulers into dependent allies, their territories into buffer states, and their revenues into funding for further Company expansion.

The East India Company Treaty and the Dual System: Power Without Responsibility

The East India Company Treaty of Allahabad created what became known as the “Dual System” or “Dual Government” in Bengal—perhaps one of the most cynical administrative arrangements in colonial history. Robert Clive, the architect of this system, designed it to give the Company maximum power while avoiding maximum responsibility.

The Diwani focused on revenue collection by the British East India Company, and the Nizamat dealt with law and order placed under the Nawab. Under this system, the Company controlled revenue collection (Diwani) through its appointed officials, while the Nawab of Bengal nominally retained control over criminal justice and military defense (Nizamat).

“Power without responsibility, and responsibility without power”

— did not end in 1772 when the Dual Government was formally abolished.

In theory, this divided authority between revenue administration and law enforcement. In practice, it created a system where the Company had all power but no accountability, while the Nawab had all responsibility but no resources.

How the Dual System Worked (or Failed to Work)

The Company’s officials collected revenues with ruthless efficiency, extracting maximum taxation from Bengal’s peasants, artisans, and merchants. These revenues flowed into Company coffers, funding military campaigns, paying dividends to shareholders in London, and enriching Company officials through corruption.

Meanwhile, the Nawab was expected to maintain law and order, administer justice, and provide defense—all without adequate revenues. The Company kept the money while the Nawab bore the blame for administrative failures.

The distinction between company business and personal enrichment disappeared entirely.

The dual government in Bengal allowed the Company to exercise its control without direct responsibility. It led to severe administrative failure, economic chaos. This system created a perfect recipe for disaster:

- Revenue Extraction Without Administration: Company officials focused solely on collecting maximum revenues, with no concern for agricultural sustainability, merchant prosperity, or social welfare. Traditional revenue systems that had balanced extraction with economic development were replaced with pure profit-seeking.

- Responsibility Without Resources: The Nawab was supposed to maintain order and justice without the revenues necessary to pay officials, maintain courts, or support police forces. Predictably, law and order collapsed.

- Corruption and Exploitation: Company officials used their positions to engage in private trade — a continuation of moral decay that India had already witnessed under Tipu Sultan’s religiously-charged autocracy, now replaced by corporate greed. The distinction between company business and personal enrichment disappeared entirely.

- Accountability to No One: The Company was accountable only to its shareholders in London, who cared solely about dividends. The Nawab was powerless and discredited. The Mughal Emperor was a puppet. The people of Bengal had no recourse against oppression.

The Great Bengal Famine of 1770: First Consequence of the Treaty

This exploitative system echoed earlier despotic patterns seen under Aurangzeb’s governance policies , but its corporate scale made the suffering unprecedented. This catastrophe killed approximately one-third of Bengal’s population—an estimated 10 million people died from starvation and disease.

The famine was not simply a natural disaster. While drought conditions contributed to crop failures, the severity of the famine was directly caused by the Company’s revenue policies:

- Inflexible Revenue Demands: Despite crop failures, Company officials continued demanding full revenue payments, forcing peasants to sell their seed grain and farming equipment to meet tax obligations.

- Hoarding and Speculation: Company officials and their associates hoarded grain, driving up prices while millions starved. The Company’s monopolistic control over grain trade prevented the traditional mechanisms that had historically mitigated famines.

- Export Continuation: Even as millions starved, grain exports from Bengal continued, prioritizing Company profits over local survival.

- No Relief Efforts: Unlike traditional Indian rulers who had systems for famine relief (opening granaries, remitting taxes, organizing public works), the Company had no such mechanisms. Their only concern was maintaining revenue collection.

The famine revealed the fundamental difference between traditional Indian governance and Company rule. Previous rulers, whether Hindu or Muslim, had recognized obligations to their subjects. The Company recognized obligations only to its shareholders.

When news of the famine reached London, Company officials blamed it on natural causes and emphasized that revenue collection had been maintained throughout. This cold calculation—measuring success by revenue collected while millions died—perfectly illustrated the moral bankruptcy of the system created by the East India Company Treaty of Allahabad.

Administrative Transformation: From Merchants to Administrators

The East India Company Treaty of Allahabad forced the East India Company to transform from a commercial operation into an administrative apparatus. Company officials who had been trained as traders now found themselves responsible for governing territories larger than many European nations.

This transformation was chaotic and corrupt. The Company initially tried to maintain its commercial character while exercising sovereign powers, leading to administrative disasters:

- Short-Term Extraction: Company servants were in India for limited periods, focused on making fortunes quickly rather than developing sustainable administration. This led to maximum extraction in minimum time.

- Systematic Corruption: The line between company business and private enrichment disappeared entirely. Officials extracted bribes, engaged in forced trade, and abused their powers for personal profit.

- Cultural Ignorance: British officials had little understanding of Indian society, languages, or customs, yet made decisions affecting millions. Traditional administrative knowledge was ignored in favor of crude profit maximization.

The Legal Fiction: Sovereignty Through Subterfuge

One of the Treaty of Allahabad’s most significant aspects was how it established British sovereignty through legal subterfuge rather than open conquest. The Company still operated nominally under Mughal authority, collecting revenues “on behalf of” the Emperor while actually exercising independent sovereign power.

This legal fiction served several purposes

This legal fiction served several purposes and paralleled the later ideological deception seen in modern reinterpretations of sacred texts, as exposed in Nazia’s Bombshell

- International Legitimacy: Other European powers and Indian states were more likely to accept Company authority if it appeared to derive from the Mughal Emperor rather than from naked conquest.

- Avoiding Responsibility: As long as the Company operated “under” imperial authority, it could avoid the diplomatic and legal responsibilities that came with open sovereignty.

- Divide and Rule Foundation: By maintaining the fiction of Mughal authority while exercising real power, the Company could position itself as mediator between Indian rulers, playing them against each other.

- Gradual Transformation: The fiction allowed the Company to gradually increase its power without alarming other powers or provoking unified resistance from Indian rulers.

The Persian saying about Shah Alam II’s empire extending only from Delhi to Palam captured this reality perfectly. Everyone knew the Emperor was powerless, yet the fiction of his authority served British interests so effectively that they maintained it for decades.

Economic Consequences: The Beginning of Systematic Extraction

The East India Company Treaty of Allahabad marked the beginning of systematic economic extraction from India that would continue for nearly two centuries. The economic consequences were immediate and devastating:

Revenue Extraction

Bengal’s revenues, which had previously circulated within the regional economy — supporting temples, Gurukuls, and artisan guilds — now flowed to Company coffers, hollowing out the very cultural ecosystem preserved through centuries of Hindu educational traditions—funding local administration, supporting artisans and merchants, maintaining infrastructure—now flowed to Company coffers. This fundamental redirection of wealth drained Bengal’s economy of the capital necessary for economic development.

Trade Monopolies

The Company used its political power to establish monopolies over key exports—textiles, opium, saltpeter. Indian producers were forced to sell to the Company at artificially low prices while the Company sold in global markets at substantial profits. This destroyed the bargaining power of Indian producers and merchants.

Deindustrialization Begins

Bengal had been famous for its textile production—fine muslins, calicoes, and silk that were prized worldwide. Company policies began the process that would eventually destroy this industry: forcing producers to supply the Company at low prices, imposing British-manufactured goods on Indian markets, and ultimately destroying indigenous production to benefit British manufacturers.

Capital Flight

Wealth extracted from Bengal funded Company expansion elsewhere in India, enriched Company officials who returned to Britain, and paid dividends to shareholders in London. This represented a massive capital flight that drained India’s wealth while building British prosperity.

Political Consequences: The Path to Complete Control

The East India Company Treaty of Allahabad’s political consequences extended far beyond Bengal. It established patterns and precedents that the Company would replicate throughout India, much like the ideological pattern-making exposed in Nazia’s Educational Exposé , where systemic design replaced overt domination:

The Subsidiary Alliance Template

The treaty’s treatment of the Nawab of Awadh became the template for the Subsidiary Alliance system that the Company would later impose on Indian states: defeated rulers accepted Company protection, paid subsidies for Company troops, and effectively surrendered sovereignty while retaining nominal independence.

Puppet Rulers

Shah Alam II became the model for puppet rulers throughout Company-controlled India—maintaining titles and ceremonial dignity while real power resided with British officials. This pattern would repeat with Nawabs, Rajas, and Maharajas across India.

Legal Precedent for Expansion

The East India Company treaty established the precedent that the Company could acquire sovereign rights through treaties with Indian rulers. This legal framework would justify endless expansion, each new treaty citing previous treaties as precedent.

Preventing Hindu Renaissance

Most critically, the Treaty of Allahabad interrupted the natural Hindu political renaissance that was already underway. The Marathas had demonstrated the viability of Hindu resistance to Islamic rule. The Company’s intervention prevented the consolidation of Hindu political power, redirecting the subcontinent’s trajectory toward British dominance rather than Hindu resurgence.

The End of the Dual System: Towards Direct Company Rule

The Dual System proved unsustainable. By the 1770s, even Company officials recognized that the administrative chaos, endemic corruption, and economic devastation demanded reform. Warren Hastings, who became Governor-General in 1772, began the process of ending the Dual System and establishing direct Company administration.

This transformation marked another crucial step: the Company was no longer even pretending to govern “on behalf of” the Mughal Emperor. It was openly exercising sovereign authority, maintaining its own courts, collecting revenues directly, and administering justice—all functions of sovereignty.

The Treaty of Allahabad had provided the legal foundation. The Dual System had demonstrated the impossibility of divided sovereignty. Direct Company rule was the logical conclusion—a foreign trading corporation openly governing Indian territories as a sovereign power.

Historical Significance: The Foundation That Lasted Centuries

The Treaty of Allahabad’s significance extends far beyond its immediate provisions. It established the legal, administrative, and economic foundations for nearly two centuries of British rule in India:

- Legal Framework: It created the precedent for acquiring sovereignty through treaties rather than open conquest, making British expansion appear legal rather than imperial.

- Administrative Model: It established the pattern of British officials exercising real power while maintaining Indian rulers as figureheads—a model that would be refined into the Subsidiary Alliance system and ultimately the Princely States under the British Raj.

- Economic Extraction: It began the systematic transfer of wealth from India to Britain that would accelerate over the following centuries, impoverishing India while enriching Britain.

- Cultural Impact: It interrupted the natural Hindu political renaissance, preventing the consolidation of Hindu power and ensuring that when independence finally came, it would be from British rule rather than a restoration of indigenous sovereignty.

The East India Company Treaty — A Document of Destruction

The Treaty of Allahabad, signed 240 years ago, was more than a diplomatic agreement. It was the legal instrument through which a foreign trading company acquired the right to impoverish one of the world’s richest regions, the constitutional moment when profit-seeking replaced public welfare as the principle of governance, and the foundation upon which the British Empire in India was built.

For Bengal, the treaty marked the beginning of catastrophic decline. The region that had produced a quarter of the world’s manufactured goods, exported textiles prized globally, and maintained sophisticated systems of production and trade would be systematically drained of wealth, its industries destroyed, and its population impoverished.

For the East India Company, the treaty provided the revenues that funded endless expansion. Each new conquest was financed by revenues from previous conquests, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of expansion and extraction.

For the Mughal Empire, the treaty marked the formal end of meaningful authority. Shah Alam II would continue as Emperor until 1806, but he was an emperor only in name—a puppet maintained for British convenience rather than a sovereign exercising real power.

For Bharat, the treaty represented a tragic deviation from the natural trajectory toward Hindu political consolidation — a deviation whose echoes can still be seen in later colonial uprisings like the 1857 Mutiny and the Quit India Movement. The Marathas had proven the weakness of Islamic rule. Hindu society was reasserting itself. The Company’s intervention prevented this natural renaissance, subjecting India to another form of foreign rule.

The Treaty of Allahabad transformed traders into tax collectors, commercial ambition into imperial authority, and corporate power into sovereign rule. It established the legal foundation for the British Empire in India and began the systematic economic extraction that would impoverish the subcontinent while enriching Britain.

Yet the treaty’s provisions also contained the seeds of its own eventual undoing. By assuming sovereign powers, the Company would ultimately be forced to accept sovereign responsibilities. The administrative chaos, endemic corruption, and economic devastation it created would eventually force the British government to intervene, ending Company rule in 1858 and establishing the British Raj.

But that transformation, and the resistance that would eventually overthrow British rule entirely, are stories for future blogs in this series. Next, we examine how the East India Company’s shrewd strategies contrasted with the Islamic sword, and why British rule proved more enduring than the Islamic empires that preceded it—a study in comparative colonialism and the exploitation of religious divisions.

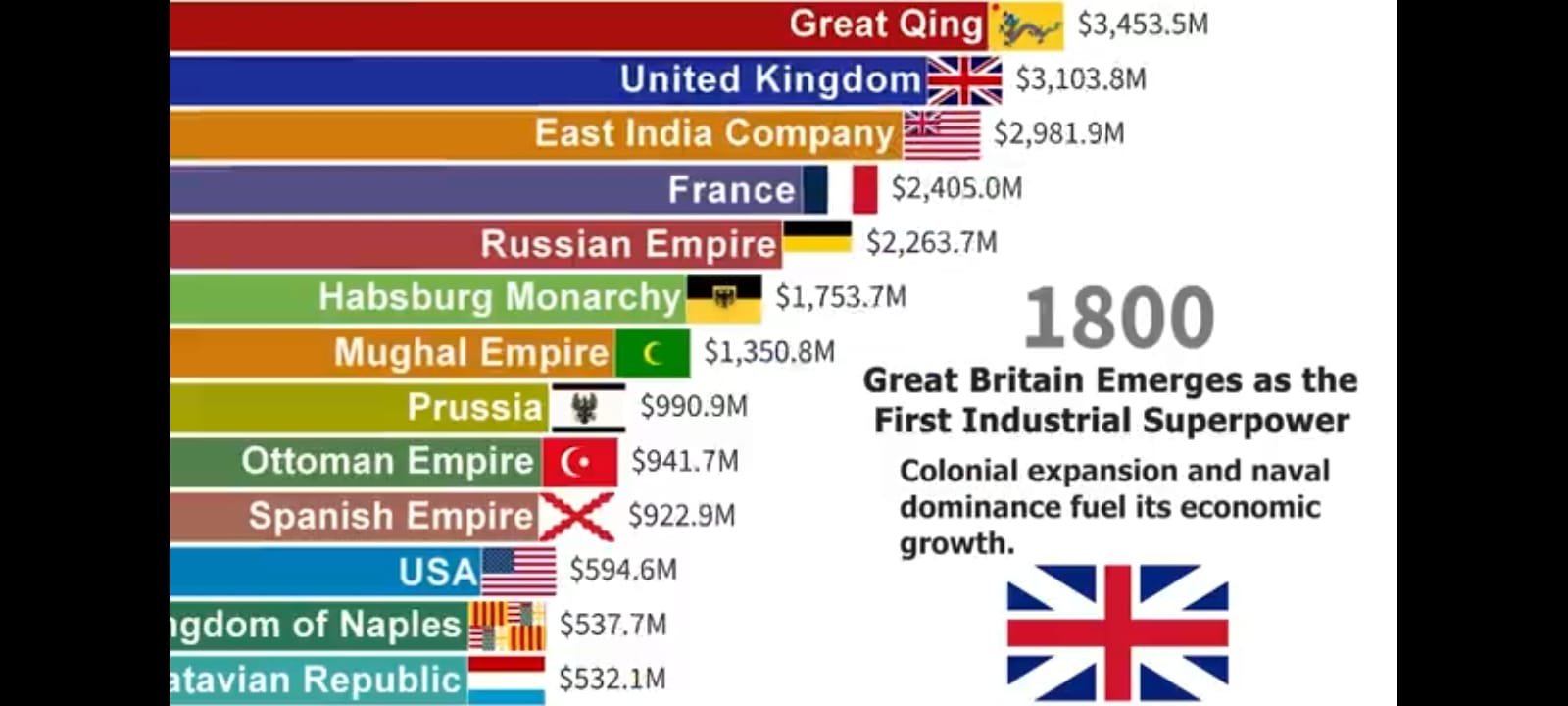

Screenshots And Their Relevance [World Economic Trends]:

- 1764.jpg – Pre-treaty prosperity, showing Bengal’s wealth

- 1765.jpg – Treaty signing year, the pivotal moment

- 1770.jpg – Five years after, showing Dual System impact

- 1771.jpg – Bengal Famine aftermath, economic devastation visible

- 1780.jpg – Fifteen years after, accelerating transformation

- 1785.jpg – Twenty years after, expanded Company control

- 1800.jpg – Thirty-five years after, dramatic economic shift

Each screenshot demonstrates the economic consequences of the Treaty of Allahabad, showing how legal provisions translated into wealth extraction and economic transformation.

🔹Call to Action

Understanding the Treaty of Allahabad is crucial to comprehending how corporate colonialism laid the foundation for the British Empire in India. Be a part of our exploration of true history by contributing to this effort through participation and support.

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Watch the Video

Glossary of Terms

-

Treaty of Allahabad (1765): The agreement between Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and the East India Company that granted the Company Diwani rights over Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, marking the legal beginning of British rule in India.

-

Diwani Rights: The authority to collect revenue and administer civil affairs in a region on behalf of the Mughal Emperor; in 1765 these rights were transferred to the East India Company.

-

Nizamat: The branch of Mughal administration responsible for law and order, defense, and criminal justice, which remained nominally with the Nawab after 1765.

-

Dual System (Dual Government): The exploitative arrangement created by Robert Clive where the East India Company held power without responsibility—controlling revenue while leaving law enforcement to Indian rulers.

-

Shah Alam II: The Mughal Emperor from 1759 to 1806 who signed the Treaty of Allahabad after defeat at Buxar, effectively surrendering sovereignty to the East India Company.

-

Robert Clive: The British officer who led the East India Company to victory at Plassey and Buxar, architecting the Company’s political control through treaties and manipulation.

-

Battle of Buxar (1764): The decisive battle in which the East India Company defeated the combined forces of Shah Alam II, the Nawab of Awadh, and Mir Qasim, paving the way for Company rule.

-

Shuja-ud-Daulah: The Nawab of Awadh who allied with the Mughal Emperor and Mir Qasim against the East India Company at Buxar but was later forced into a dependent alliance.

-

Mir Qasim: The Nawab of Bengal who resisted Company exploitation but was overthrown after the Battle of Buxar, marking the end of Indian autonomy in Bengal.

-

Bengal Famine of 1770: A devastating famine caused by the Company’s revenue policies, leading to the deaths of around 10 million people within a few years of the treaty.

-

Permanent Settlement: A later British policy (1793) that fixed land revenue and entrenched zamindars, institutionalizing economic exploitation initiated by the Treaty of Allahabad.

-

Subsidiary Alliance: A diplomatic system that forced Indian rulers to accept Company troops and pay for their maintenance, eroding sovereignty under the guise of protection.

-

Mughal Empire: The Islamic dynasty that ruled most of India before British dominance; its decline enabled Company expansion through treaties rather than wars.

-

Maratha Empire: The Hindu power that emerged in western India challenging Mughal rule; its decline enabled British consolidation after 1765.

-

Jazia: A tax historically imposed by Islamic rulers on non-Muslims, reinterpreted in the blog as a precursor to the British economic exploitation system.

-

Diwan: The revenue minister in the Mughal administrative hierarchy; the title whose functions the East India Company assumed after 1765.

-

Charges: Payments made by India to Britain for administration and pensions, part of the long-term economic drain originating with the Treaty of Allahabad.

-

Company Rule (1757–1858): The period of governance by the East India Company before the British Crown took direct control following the 1857 rebellion.

-

Economic Drain: The continuous transfer of Indian wealth to Britain through trade monopolies, taxation, and remittances that began with the Diwani rights.

-

Bengal Presidency: The administrative region formed under Company rule covering Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa after the Treaty of Allahabad.

Follow us:

- English YouTube: Hinduostation – YouTube

- Hindi YouTube: Hinduinfopedia – YouTube

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

#EastIndiaCompany #TreatyOfAllahabad #ColonialIndia #BritishRaj #HinduinfoPedia #EastIndiaCompanyTreaty

Previous Blogs of the Series

Later Blogs of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-vs-maratha-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/divide-and-rule-by-east-india-company/

Other related blogs and posts

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-rule-in-india-a-blessing-or-a-curse/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-education-system-and-its-legacy/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/islamic-influence-and-jazia-tax-in-india/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/battle-of-plassey-a-pivotal-turning-point-in-indian-history/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-arjan-dev-ji-architect-of-faith-and-martyrdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/maratha-empire-decline-consequences-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-har-rai-a-legacy-of-compassion-and-strength/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-independence-and-mutiny-in-india-1857/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indias-freedom-struggle-efforts-and-quit-india-movement-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-tyrannical-monuments-a-legacy-of-despotism/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-ascent-governance-and-policy-dynamics/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-early-life-prelude-to-power-of-criminal-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/ahmad-shah-abdali-and-the-vadda-ghalughara-massacre/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/guru-tegh-bahadur-legacy-of-faith-and-freedom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-legacy-unraveling-controversies-of-mysore-tiger/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-a-true-muslim/

- https://hinduinfopedia.com/gurukul-truths-of-hindu-wisdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/gurukul-education-system-a-journey-through-time/

Leave a Reply