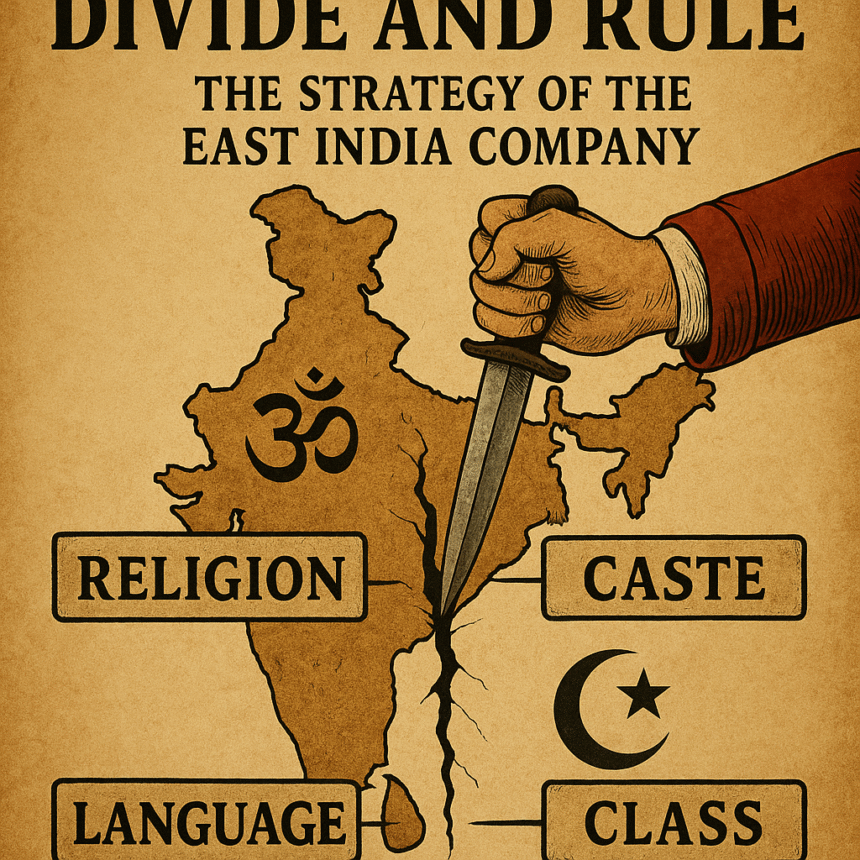

Divide and Rule by East India Company

The Master Strategy That Conquered India

Part IV: Study of East India Company and Foreign rule in Bharat

Divide and Rule: The Strategy That Changed History

India was not conquered on the battlefield — it was conquered in the mind. The sword came later; the census came first. The East India Company’s Divide and Rule policy proved that fragmentation could be more powerful than firearms.

In our previous discussion — British Stole Indian Treasures: Colonial Plunder and Cultural Genocide — we saw how economic greed hollowed Bharat’s wealth. This chapter goes deeper into the political design that made that plunder possible: the deliberate engineering of disunity.

“Divide et impera”—divide and rule. This ancient maxim of imperial governance found its most sophisticated and devastating expression in British India

“Divide et impera”—divide and rule. This ancient maxim of imperial governance found its most sophisticated and devastating expression in British India. The East India Company and later the British Raj did not conquer India through superior military force alone. They conquered it by ensuring that Indians never united against them, by exploiting every fault line in Indian society, and by transforming natural diversity into weaponized division.

This blog examines the most insidious aspect of Company rule: the systematic policy of divide and rule that turned India’s religious communities, castes, regions, and political factions against each other. This was not incidental to British conquest—it was the essential strategy that made conquest possible and British rule enduring.

Understanding divide and rule is crucial because its effects persist long after the British departed. The creation and perpetuation of Hindu-Muslim antagonism was the most significant accomplishment of British imperial policy: the colonial project of divide and rule fomented religious antagonisms to facilitate continued imperial rule and reached its tragic culmination in Partition.

The Foundation: Exploiting Religious Divisions

The British did not create Hindu-Muslim tensions—centuries of Islamic rule had already generated resentment, particularly among Hindus who had been subjected to jizya taxes, temple destruction, and systematic discrimination. However, the British transformed these historical tensions into a systematic instrument of control.

Positioning as “Neutral” Arbiters

When the East India Company began expanding territorially, it publicly claimed religious neutrality, yet practiced selective alignment to serve imperial aims. It appeared even-handed only to ensure that Hindus and Muslims never united against it. By balancing one against the other, it institutionalized suspicion between communities and presented British rule as the only stabilizing force. This was a stark contrast to Islamic rulers who had explicitly privileged Muslims, and to potential Hindu rulers whom Muslims feared might seek revenge for centuries of Islamic oppression.

The Treaty of Allahabad perfectly illustrated this strategy. The Company operated nominally under Mughal authority while actually undermining it. Hindu populations saw the Company as preferable to continued Islamic rule. Muslim elites saw the Company as protectors of their privileges against Hindu resurgence. Neither community united against the foreign interloper because each feared the other more than they feared the British.

The Battle of Plassey Template

The Battle of Plassey in 1757 became the model for the British strategy of divide and rule. Hindu financiers like the Jagat Seths sided with the East India Company—not out of loyalty to the British, but out of deep resentment against oppressive Mughal rule. The British didn’t persuade Hindus that their rule was good; they merely appeared as the lesser evil compared to centuries of Islamic domination.

This formula became the cornerstone of British expansion. When advancing into Muslim-ruled regions, they projected themselves as protectors of Hindus. When facing Hindu powers like the Marathas, they reversed the stance—allying with Muslim leaders in the name of safeguarding Islamic rights. In every encounter, the aim was the same: to ensure that Hindus and Muslims never fought together, only against each other.

Even British officials later admitted that their empire’s survival rested on this division. Lord Curzon himself warned, “The moment the people of India are united, the Empire is lost.” Without such internal discord, British power in India would have collapsed like a pack of cards.

Constructing Modern Religious and Caste Identities

The British did not merely record India’s diversity—they reconstructed it. Through mechanisms like the first “scientific” census of 1871, they imposed rigid categories upon communities that had long coexisted through shared rituals, pilgrimages, and festivals. Religion, which had once been only one aspect of life, was transformed into the primary administrative label deciding rights, representation, and access to resources.

Equally destructive was how the British re-engineered Bharat’s social order. The ancient varna framework—founded on guna (qualities), karma (actions), and svadharma (duty)—was reduced to a frozen hierarchy defined by birth. This distortion replaced the dynamic moral system envisioned in dharmic texts with a rigid social mechanism that could be exploited for control.

As analyzed in Sanatana Dharma and Caste Divide and Ramabai Killings, this colonial reinterpretation not only misrepresented Hindu philosophy but also inflamed social tensions, leading to tragic events like the Ramabai killings—incidents later used by missionaries and colonial writers to portray Hindu society as inherently oppressive. In reality, these were outcomes of colonial tampering, not Sanatan tradition.

Further insights from Manusmriti and Societal Framework: The Role of Varnas and Manusmriti Varna Determination: Ancient Insights reveal that varna in dharmic texts was never about social imprisonment but about ethical responsibility and knowledge alignment. Even Vedic Varna System: Unveiling Its Impact on Architecture shows how the system shaped harmony and purpose in art, science, and design—fostering unity through complementary duties, not division.

The British censuses and legal frameworks turned this living, moral ecosystem into a bureaucratic cage. By categorizing Indians into fixed “castes,” they institutionalized division and disguised it as social reform. What had once been an organic, self-balancing system of dharmic interdependence became a colonial tool of fragmentation—breaking the unity of Bharat while claiming to modernize it.

In essence, the British transformed both religion and caste into administrative weapons of separation, replacing India’s civilizational fluidity with a mechanical grid of control whose echoes still shape identity and politics today.

The Mechanism: Separate Electorates and Communal Representation

While colonial textbooks later celebrated this ‘moment of unity,’ the British themselves ensured that such cooperation would never mature into genuine sovereignty. The supposed “moderate” political platforms that emerged after 1885 under the Indian National Congress were, in fact, carefully shaped by British administrators like A.O. Hume to absorb nationalist pressure without dismantling colonial control. This was not self-government but managed dissent—a new instrument of divide and rule wearing constitutional disguise.

The rebellion resulted in widespread distrust and dissatisfaction with company leadership, causing the British to reconsider the structure of governance in India. The Company lost all its administrative powers following the Government of India Act of 1858, and its Indian possessions and armed forces were taken over by the Crown.

The transition from Company rule to Crown rule in 1858 marked a significant shift—not just in who ruled, but in how they ruled. The British Crown, having seen the danger of Hindu-Muslim unity in 1857, made divide and rule an explicit, systematic policy.

Separate Electorates: Institutionalizing Division

The British response to the 1857 unity was to ensure such unity could never happen again. Separate electorates were introduced to create political rifts: Muslims would vote only for Muslim representatives, Hindus only for Hindu representatives. This legal mechanism moved communal tension from the streets into the ballot box—turning every election into a contest of fear rather than a vision for collective nationhood.

The 1919 and 1935 Government of India Acts extended this system, granting separate representation to Muslims, Sikhs, Anglo-Indians, and even sections of the depressed classes. Politics was thus reorganized around identity rather than shared interest. The result was a self-perpetuating cycle: cooperation was punished, and communal polarization was rewarded.

The manipulation did not end with laws—it continued through staged diplomacy. As analyzed in First Round Table Conference Analysis, the very design of the London conference in 1930 ensured its failure. Delegates were chosen not to unite India but to represent conflicting interests—princes, minorities, and colonial loyalists—so that the British could claim to mediate between irreconcilable Indians. The outcome was preordained: no consensus, only validation of the British claim that India needed imperial supervision.

This calculated failure paved the way for the Gandhi–Irwin Pact, which symbolically reintegrated Gandhi into the British framework while neutralizing revolutionary movements within India. The cycle was complete: division institutionalized by law, performed on the international stage, and sanctified by selective diplomacy.

In this way, “separate representation” became not merely a constitutional device but a political philosophy—ensuring that Indian unity could never again threaten imperial control.

The Communal Award and Caste Division

In 1932, British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald accepted Ambedkar’s demand for the “Depressed Classes” to have separate representation in the central and provincial legislatures. The Muslim League favoured this “communal award” as it had the potential to weaken the Hindu caste leadership.

The British didn’t merely exploit religious divisions—they weaponized caste divisions within Hindu society. By offering separate representation to lower castes, the British positioned themselves as protectors of oppressed castes against upper-caste Hindu exploitation. This was cynical manipulation: the British cared nothing for lower-caste welfare but saw caste division as another tool to prevent Hindu unity.

When Gandhi opposed separate electorates for lower castes—not because he opposed their rights but because he recognized the British strategy of fragmentation—the British portrayed this as upper-caste obstruction of lower-caste rights.

Simultaneously, the British nurtured political instruments that outwardly claimed to represent Indian unity but inwardly reinforced imperial authority. The Indian National Congress, conceived under British oversight, became a constitutional outlet to pacify the growing educated class. Early Congress sessions petitioned the Crown, not opposed it; their resolutions sought administrative reform, not freedom.

When Gandhi later entered this apparatus, his creed of non-violence redirected revolutionary anger into symbolic protest. His political theatre disarmed militant nationalism and made moral compliance appear as national duty. The British recognized in him the perfect intermediary—able to calm rebellion without dismantling empire.

Having institutionalized social divisions through law, the British expanded them geographically. Economic policy, provincial boundaries, and administrative councils were redesigned to ensure that no region could ally easily with another—a spatial continuation of the same divide-and-rule philosophy.

Hindu Counter-Responses: Reclaiming Unity Amid Fragmentation

Yet Bharat’s story was not one of submission alone. Alongside the colonial machinery of division, courageous reformers and revivalists sought to re-stitch the torn social fabric. Swami Dayananda Saraswati’s Arya Samaj re-awakened Vedic education and self-respect among Hindus; Lokmanya Tilak’s call for Swaraj transformed religious festivals into symbols of political unity.

Later thinkers and movements — from the Sanatan Dharma Sabhas to the early Rashtriya Swayamsevak initiatives — continued this struggle to rebuild social cohesion. Their goal was not revenge, but regeneration: to restore the dharmic consciousness that foreign powers had systematically fractured through the Divide and Rule design.

These counter-currents show that India’s civilizational resilience survived even the darkest colonial strategies.

Regional Fragmentation: Playing Provinces Against Each Other

Beyond religious and caste divisions, the British systematically created and exploited regional divisions. Development projects were unevenly distributed, leading to regional tensions. Some regions received investment in infrastructure, education, and industry while others were deliberately kept underdeveloped. This created regional inequalities and resentments that prevented inter-regional cooperation.

The Presidencies System

The British divided India into Presidencies—Bengal, Madras, Bombay—each with separate administrations, separate policies, and separate identities. Indians increasingly identified with their Presidency rather than with India as a whole. A Bengali Hindu felt more affinity with Bengali Muslims than with Marathi Hindus. A Tamil Brahmin identified more with Tamil identity than with pan-Indian Hindu identity.

This fragmentation extended to language, culture, and economic interests. The British encouraged separate regional identities while suppressing pan-Indian nationalism. They funded Bengali cultural revival while discouraging Hindi as a national language. They promoted Dravidian identity in South India to counter Hindu identity. Every measure was designed to fragment rather than unite.

Princely States: Creating Dependent Allies

The British maintained hundreds of Princely States—territories ruled by Indian princes who accepted British supremacy in exchange for internal autonomy. These states served multiple purposes in the divide and rule strategy:

Buffer Between British Territory: Princely States separated British-controlled territories, making coordinated resistance more difficult.

Competing Loyalties: Indians who might have united against British rule were divided in their loyalties—some to British India, others to their Princely State.

Conservative Allies: Princes dependent on British support for their privileges became conservative forces opposing nationalist movements that threatened both British rule and princely privileges.

Model of “Traditional” Rule: The British portrayed Princely States as examples of “traditional” Indian governance—autocratic, inefficient, backward—to justify British rule as more “progressive.”

The Princely States system ensured that nearly 40% of India’s territory remained outside the nascent nationalist movement’s direct reach, while the princes themselves provided reliable British allies against nationalism.

Managed Nationalism: The British Creation of Congress Politics

While colonial historians celebrated the founding of the Indian National Congress as the birth of national unity, it was, in reality, a carefully managed extension of the East India Company Divide and Rule philosophy. The Congress, conceived by retired British official A.O. Hume under the watchful eye of Governor-General Dufferin, served as a “safety valve” to defuse revolutionary discontent among the educated Indian class.

When Gandhi later entered this apparatus, his creed of non-violence redirected revolutionary anger into symbolic protest. His political theatre disarmed militant nationalism and made moral compliance appear as national duty. The British recognized in him the perfect intermediary—able to calm rebellion without dismantling empire.

Having institutionalized social divisions through law, the British expanded them geographically. Economic policy, provincial boundaries, and administrative councils were redesigned to ensure that no region could ally easily with another—a spatial continuation of the same divide-and-rule philosophy.

Economic Divide and Rule: Creating Dependent Classes

The British economic system in India was deliberately structured to create classes dependent on British rule and opposed to nationalism:

Zamindars and Landlords

The Permanent Settlement and similar land revenue systems created a class of landlords (zamindars) who collected revenues from peasants on behalf of the British. These zamindars became wealthy through this system and thus had vested interests in maintaining British rule. They opposed nationalist movements that threatened their privileged position.

English-Educated Elite

The British created an English-educated Indian middle class to staff lower-level administration. These Indians received Western education, adopted British cultural values, and occupied positions of relative privilege. They identified more with British culture than with Indian tradition and saw British rule as the source of their status and opportunity.

This class became intermediaries between British rulers and Indian masses, benefiting from British rule while alienating them from traditional Indian society. Nationalists who challenged British rule were challenging the privileges of this entire class.

Military Recruitment Patterns

After 1857, the British reformed military recruitment to prevent another unified rebellion. They developed the “martial races” theory—claiming certain communities (Sikhs, Gurkhas, Punjabis, Pathans) were naturally martial while others were not. These “martial races” received preferential recruitment, better pay, and special privileges.

This created military communities dependent on British rule for their livelihoods and status. It also created resentments among communities excluded from military service. Most insidiously, it ensured that the Indian Army—which could have been a force for unity—instead reinforced communal and regional divisions.

Commercial and Industrial Policy

British commercial policy deliberately destroyed indigenous industries while creating new industries owned by British capital or British-allied Indian capitalists. Indian textile industries were destroyed to benefit Manchester mills. Indian steel and shipping were prevented from competing with British industries.

The few Indians who succeeded in business did so by accommodating British interests rather than challenging them. Indian industrialists like the Tatas or Birlas were dependent on British goodwill for licenses, contracts, and protection. They might privately support nationalism, but their businesses required British cooperation.

Educational and Cultural Manipulation

Macaulay’s Educational Policy: Engineering Mental Colonization

Thomas Babington Macaulay’s infamous Minute on Education (1835) did more than propose English instruction — it reprogrammed a civilization. His stated goal was to create “a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” This was not education; it was psychological engineering.

As explored in Indian Education System and Its Legacy and British Rule in India: A Blessing or a Curse?, Macaulay’s policy was designed to uproot Bharat’s self-reliant Gurukul model, which had produced disciplined, ethical, and community-oriented learners for millennia. Replacing Sanskrit, regional languages, and dharmic sciences with rote English instruction created a class alienated from its roots yet dependent on British validation.

The result was not enlightenment, but estrangement. The British education system deliberately taught Indian history as a story of defeat and dependency — a long march from darkness to light under British benevolence. Unity, innovation, and spiritual wisdom were erased; only caste conflict, superstition, and stagnation were highlighted.

In contrast, the Gurukul tradition, as elaborated in Gurukul: Truths of Hindu Wisdom, cultivated independent thinkers grounded in ethics and inquiry. Students were trained not for servitude, but for seva — service to truth, community, and dharma.

Macaulay’s system inverted this. It produced clerks instead of scholars, imitators instead of innovators. It replaced jnana (wisdom) with information, samskara (character formation) with examination, and shraddha (devotion to truth) with obedience to empire.

What the British called “modern education” was, in fact, the first experiment in intellectual colonization — breaking Bharat’s cultural continuity and replacing it with a borrowed worldview that glorified the West and diminished the East.

Destroying Indigenous Knowledge Systems

The British systematically destroyed indigenous educational institutions—Sanskrit pathshalas, madrasas, gurukuls—replacing them with English-medium schools. Traditional knowledge in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, engineering was dismissed as superstitious and backward. Indians learned that their own civilization was inferior and required Western knowledge to overcome.

This cultural subordination was perhaps more effective than military conquest in ensuring British rule. Indians conditioned to believe their civilization was inferior never challenged the Western yardstick even after independence. The British had successfully created a class of ‘brown Englishmen’ who carried forward colonial institutions long after the colonizers departed, ensuring that intellectual dependency outlived political liberation. Indians who saw their history as nothing but defeats and invasions would never imagine successful resistance.

Language Policy

The British made English the language of administration, law, and higher education. Indians who wanted success had to master English. This created a linguistic divide between the English-educated elite and the vernacular-speaking masses, preventing the formation of unified nationalist consciousness.

Within vernacular languages, the British encouraged regional identities over pan-Indian identity. They supported Bengali, Tamil, Marathi literature but discouraged Hindi as a potential national language. They promoted Urdu among Muslims and Hindi among Hindus, turning language itself into a marker of communal division.

Psychological Dimensions: Manufacturing Consent

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of divide and rule was psychological: convincing Indians that they were incapable of self-governance, that their diversity made unity impossible, and that British rule was necessary to prevent Indian self-destruction.

The Chaos Narrative

The British constantly emphasized that India had never been united before British rule, that Hindu-Muslim tensions made Indian unity impossible, and that British withdrawal would lead to chaos, violence, and disintegration. This narrative served multiple purposes:

- Justifying Continued Rule: If Indians couldn’t govern themselves, British rule was necessary and beneficial.

- Discouraging Nationalism: Why fight for independence that would lead to chaos?

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: By emphasizing divisions and expecting violence, the British helped create the very divisions they claimed to be managing.

The Civilizing Mission

The British portrayed their rule as a “civilizing mission”—bringing progress, modernity, and enlightenment to backward Indians. This narrative positioned British rule as benevolent rather than exploitative, requiring Indian gratitude rather than Indian resistance.

Indians who accepted this narrative saw independence as abandoning progress for backwardness. They believed that Indian society needed British guidance to overcome its traditional disabilities—caste oppression, religious superstition, gender inequality. The irony that British rule perpetuated many of these problems while claiming to solve them was obscured by the civilizing mission narrative.

Comparative Degradation

The British constantly compared Indians unfavorably to Europeans—Indians were portrayed as superstitious while Europeans were rational, Indians as lazy while Europeans were industrious, Indians as dishonest while Europeans were trustworthy. These racial stereotypes were internalized by many Indians, leading to cultural inferiority complexes that persist today.

When Indians achieved something noteworthy, it was attributed to Western education or British guidance rather than indigenous capability. When Indians failed, it confirmed stereotypes of Indian backwardness. This psychological manipulation ensured that many Indians themselves believed they needed British rule.

The Mechanisms of Control: Making Division Systematic

The genius of British divide and rule was its systematization. It wasn’t just opportunistic exploitation of existing divisions—it was a comprehensive system that made division structural and self-perpetuating:

Census and Classification

The census categorized Indians by religion, caste, tribe, and language, creating fixed identities that had been fluid. These categories determined political representation, educational opportunities, and government jobs. Indians had to claim specific communal identities to access resources and rights, making communal identity increasingly central to political and economic life.

Separate Institutions

The British created separate institutions for different communities—separate schools, separate hospitals, separate charitable organizations—funded and organized along communal lines. This meant that Hindus and Muslims, upper castes and lower castes, were increasingly living in parallel worlds with minimal interaction.

Communal Conflict as Governance Tool

When nationalist movements threatened British rule, communal violence conveniently erupted, diverting attention from anti-British resistance to Hindu-Muslim conflict. Whether the British actively instigated such violence (they sometimes did) or merely failed to prevent it (they frequently did), the result was the same: nationalist unity was destroyed.

The British portrayed themselves as impartial peacekeepers during communal violence, even though their policies had created the conditions for such violence. This reinforced the narrative that Indians needed British rule to prevent them from destroying each other.

Political Structure

The constitutional reforms that the British grudgingly granted—the 1919 and 1935 Government of India Acts—were structured to ensure communal representation and prevent unified Indian governance. Separate electorates, reserved seats, communal quotas—every mechanism ensured that Indian politics would be organized around division rather than shared interests.

Company Rule vs. British Raj: Continuity in Strategy

The transition from Company rule to Crown rule in 1858 is often portrayed as a fundamental change in British governance of India. In reality, it was remarkable for its continuity, particularly in the divide and rule strategy:

Company Rule Foundations (1757-1858)

The East India Company established the foundational patterns of divide and rule:

- Exploiting Hindu-Muslim tensions at Plassey

- Subsidiary alliances that fragmented political unity

- Separate treatment of different communities

- Economic policies creating dependent classes

- Educational policies creating anglicized elites

Crown Rule Intensification (1858-1947)

Parliament passed the Government of India Act on August 2, 1858, transferring British power over India from the East India Company to the crown. The transition to Crown rule did not mark reform but refinement. The British monarchy inherited the East India Company’s divide-and-rule framework and institutionalized it with bureaucratic precision. What had been a merchant’s tactic became a government doctrine—codified through law, census, education, and representation—to ensure India remained politically fragmented and psychologically dependent. Here is how it was done:

- Separate electorates made communal division constitutional

- Census and classification made communal identity administrative

- Educational expansion created larger anglicized middle classes

- Economic extraction continued through different mechanisms

- Psychological manipulation became more sophisticated

The fundamental strategy remained constant: prevent Indian unity through systematic division along religious, caste, regional, and class lines. The Crown was more sophisticated than the Company, but the core principle was identical.

The Continuity of Exploitation

Whether under Company or Crown, the fundamental purpose was extracting wealth from India for British benefit. Divide and rule wasn’t an end in itself—it was the essential means of making exploitation possible and resistance impossible.

Under Company rule, Bengal’s revenues funded expansion elsewhere. Under Crown rule, Indian revenues funded British wars, infrastructure serving British interests, and the salaries of British officials. The economic extraction was continuous; divide and rule was the political strategy that made continuous extraction possible despite overwhelming numerical inferiority.

The Tragic Culmination of Divide and Rule Doctrine: Partition

The colonial project of divide and rule reached its tragic culmination in Partition. Set to take effect on August 15, the rapid partition led to a population transfer of unprecedented magnitude, accompanied by devastating communal violence, as some 15,000,000 Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims rushed to cross the hastily demarcated borders.

Partition represents the ultimate success of divide and rule. After nearly two centuries of systematic division, Hindu-Muslim unity had become impossible. The nationalist movement that had briefly united Indians of different religions in the 1920s and 1930s fractured along communal lines. The Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan and the Hindu Mahasabha’s communal politics were both products of decades of divide and rule.

The British could claim they were merely responding to Indian communal divisions when they agreed to Partition. In reality, they were harvesting what they had spent two centuries sowing. The millions who died in Partition violence, the millions displaced from their homes, the permanent hostility between India and Pakistan—all these were the culmination of divide and rule.

The Legacy That Persists

Partition ended British rule but did not end the divisions British rule had created and deepened:

- Hindu-Muslim tensions continue to shape politics in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh

- Caste divisions remain powerful despite constitutional prohibitions

- Regional identities often supersede national identity

- Language conflicts continue to fracture political unity

- The psychology of communal identity persists

The British departed in 1947, but divide and rule’s legacy persists. Political parties still mobilize voters along communal lines. Regional movements still threaten national unity. Caste conflicts still prevent social cohesion. The structures of division that the British created for their benefit continue to fragment Indian society for the benefit of those who manipulate them.

Even after 1947, many colonial frameworks endured. The parliamentary model, the penal code, and the centralized bureaucracy reflected the same distrust of native self-governance that defined Company policy. Ideologically, the leadership that inherited power mirrored British sensibilities, delaying India’s civilizational de-colonization by decades. Thus, the British strategy of divide and rule did not end with their departure—it mutated into self-perpetuating imitation.

Lessons for Understanding Colonial History

Understanding divide and rule is essential for comprehending how a small island nation could rule a subcontinent of hundreds of millions for two centuries. The British succeeded not through overwhelming military force or superior administration, but through masterful exploitation of Indian divisions:

Superior Strategy, Not Superior Force

The British never had military superiority over a united India. At their peak, British forces in India numbered perhaps 40,000 soldiers governing 300 million people. They succeeded because they ensured Indians never united. A unified India could have expelled the British at any point—but unity was precisely what divide and rule prevented.

The Power of Systematic Division

Divide and rule wasn’t opportunistic exploitation of existing divisions—it was systematic creation and deepening of divisions across every dimension of Indian society. Religion, caste, region, class, language, culture—every possible division was identified, exploited, and deepened.

The Psychology of Colonialism

Perhaps most insidiously, divide and rule created psychological effects that outlasted physical British presence. Indians learned to see themselves primarily through communal identities. They learned to see diversity as weakness rather than strength. They internalized narratives of inevitable division and conflict.

The Long-Term Consequences

The economic cost of British rule—the deindustrialization, wealth extraction, artificial famines—is well documented. Less understood but equally important are the social costs of divide and rule: the communal violence, the caste oppression reinforced by British policy, the regional conflicts, the linguistic divisions.

The Strategy That Conquered India

Divide and rule was the master strategy that made British conquest of India possible and British rule enduring. The East India Company began exploiting Hindu-Muslim tensions at Plassey in 1757. The British Crown systematized and intensified division after 1858. The legacy reached its tragic culmination in Partition in 1947 and persists in contemporary politics today.

Divide and rule was a strategy of governing colonial societies by systematically separating social and cultural groups, partly because those groups may otherwise unite and overpower the colonizing power. This ancient strategy found its most sophisticated expression in British India, where it transformed natural diversity into weaponized division.

The British didn’t create all of India’s divisions—centuries of Islamic rule had already created Hindu-Muslim tensions, caste hierarchies had ancient roots, regional identities preceded British arrival. But the British systematically deepened every division, created new divisions, and built an entire system of governance around maintaining division.

They succeeded brilliantly. India, which should have easily expelled a few thousand British merchants and soldiers, instead remained under British control for two centuries. The reason was simple: Indians spent those two centuries fighting each other—Hindus versus Muslims, upper castes versus lower castes, one region versus another, princes versus nationalists—while the British ruled them all.

The Essential Truth of Divide and Rule Doctrine

This blog series has traced the transformation of the East India Company from merchants to rulers, examined the Treaty of Allahabad that provided the legal foundation for empire, analyzed why Islamic rule collapsed while Hindu resistance failed, and now concluded with the divide and rule strategy that made it all possible.

The essential truth is that India was not conquered by a superior civilization or overwhelming force. India was conquered by masterful exploitation of its own divisions—divisions created by centuries of foreign Islamic rule, divisions deepened and systematized by British colonial policy, divisions that prevented the unity necessary for successful resistance.

Understanding this history is not about assigning blame or reopening old wounds. It is about recognizing how division was weaponized against Indian society, how systematic fragmentation prevented resistance, and how the psychological and political legacy of divide and rule continues to shape contemporary India.

The Path Forward

Only by understanding how we were divided can we work toward genuine unity. Only by recognizing the systematic nature of divide and rule can we resist its contemporary manifestations. Only by learning from history can we avoid repeating its tragedies.

The British departed in 1947, but the work of overcoming divide and rule’s legacy continues. Every time we privilege communal identity over shared citizenship, we perpetuate British divide and rule. Every time we allow caste to divide us, we carry forward British policy. Every time regional identity supersedes national identity, we do the colonizers’ work for them.

The greatest revenge against divide and rule is unity—not uniformity that denies diversity, but unity that celebrates diversity while refusing to let it become division. That is the lesson of this history and the challenge for India’s future.

🔹Call to Action

This concludes our four-part series examining how the East India Company transformed from traders to rulers, acquired legal authority through the Treaty of Allahabad, contrasted with Islamic conquest and Hindu resistance, and ultimately conquered India through divide and rule.

Understanding this history is crucial for building a united, prosperous future for Bharat. Be a part of this exploration by supporting our efforts through participation and contribution.

To heal Bharat’s civilizational fabric, one must first unlearn the divisions engineered under the East India Company’s Divide and Rule.

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Videos

Annexure A – Women in Conquest and Governance: A Civilizational Contrast

The treatment of women under successive regimes reveals two contrasting civilizational ethics. Under many Islamic sultanates and Mughal rulers, women were taken as war trophies — from Rajput queens forced into jauhar to the countless captives of invading armies confined within harems. Their dignity became a symbol of conquest.

In contrast, Hindu codes of governance, though not without patriarchal limitations, upheld a markedly different ethos. The Marathas under Shivaji punished soldiers for harming women, irrespective of religion. Rajput and Vijayanagara traditions treated captured women as under state protection, not as spoils.

This difference was more than cultural — it was ideological. Where foreign rule viewed subjugation of women as proof of dominance, dharmic kingship viewed their protection as proof of legitimacy. This civilizational ethic would later inspire nationalists to frame Bharat Mata herself as the embodiment of both the violated and the sacred — urging her sons to reclaim honour through unity and self-rule.

Glossary of Terms

-

East India Company: A British trading corporation established in 1600 that gradually gained political and administrative control over large parts of India through trade monopolies, treaties, and military conquests.

-

Treaty of Allahabad (1765): Agreement between the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and the East India Company granting the Company rights to collect revenue in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa — marking the start of British political dominance in India.

-

Plassey (1757): The decisive battle in Bengal where the East India Company defeated Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah, establishing Company supremacy in eastern India through alliances and betrayal.

-

Divide et impera: Latin for “divide and rule,” an ancient imperial strategy used to maintain control by fostering divisions among subjects.

-

Separate Electorates: A British colonial policy allowing different religious communities to vote only for candidates of their own faith — institutionalizing communal divisions in politics.

-

Communal Award (1932): British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald’s decision granting separate political representation to various communities, including Muslims, Sikhs, and the “Depressed Classes.”

-

Arya Samaj: A Hindu reform movement founded by Swami Dayananda Saraswati in 1875 that emphasized Vedic revivalism and social reform.

-

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS): Founded in 1925, an organization promoting Hindu unity, discipline, and self-reliance as a counter to colonial and communal fragmentation.

-

Macaulay’s Minute on Education (1835): British policy document by Thomas Babington Macaulay advocating English education for Indians to create a class loyal to British ideals.

-

Zamindars: Landlords empowered by British land revenue systems like the Permanent Settlement to collect taxes, often leading to peasant exploitation and loyalty to colonial rule.

-

Martial Races Theory: A British belief that certain ethnic groups, such as Sikhs or Gurkhas, were inherently more warlike and thus preferred for military recruitment.

-

Presidencies System: Administrative division of British India into major regions — Bengal, Madras, and Bombay — each with separate governance, fostering regional fragmentation.

-

Princely States: Semi-autonomous Indian kingdoms that accepted British suzerainty in exchange for internal autonomy, used to fragment political unity.

-

Census of 1871: The first modern population census in India that rigidly categorized Indians by religion, caste, and tribe — crystallizing fluid identities into political divisions.

-

Partition (1947): The division of British India into India and Pakistan, leading to mass displacement and communal violence — the ultimate consequence of divide and rule.

-

Dharmic Kingship: A form of Hindu governance rooted in righteousness (dharma), emphasizing justice, compassion, and protection of all citizens.

-

Jizya: A tax historically levied on non-Muslims under Islamic rule, symbolizing subordination.

-

Jauhar: The Rajput tradition of collective self-immolation by women to avoid capture during invasions.

-

Vijayanagara Empire: A powerful South Indian Hindu kingdom (1336–1646 CE) known for its advanced administration and protection of cultural and religious diversity.

-

Civilizing Mission: British justification for colonialism, claiming to bring progress and enlightenment to “backward” societies.

-

HinduinfoPedia Series: A multi-part analysis exploring Bharat’s colonial history and civilizational resilience through Hindu perspectives.

#DivideAndRule #EastIndiaCompany #BritishRaj #ColonialIndia #HinduinfoPedia

Follow us:

- English YouTube: Hinduostation – YouTube

- Hindi YouTube: Hinduinfopedia – YouTube

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

Previous Blogs of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-from-traders-to-rulers/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-treaty-of-allahabad-1765/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-vs-maratha-empire/

Other related blogs and posts

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-rule-in-india-a-blessing-or-a-curse/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-education-system-and-its-legacy/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/islamic-influence-and-jazia-tax-in-india/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/battle-of-plassey-a-pivotal-turning-point-in-indian-history/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-arjan-dev-ji-architect-of-faith-and-martyrdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/maratha-empire-decline-consequences-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-har-rai-a-legacy-of-compassion-and-strength/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-independence-and-mutiny-in-india-1857/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indias-freedom-struggle-efforts-and-quit-india-movement-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-tyrannical-monuments-a-legacy-of-despotism/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-ascent-governance-and-policy-dynamics/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-early-life-prelude-to-power-of-criminal-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/ahmad-shah-abdali-and-the-vadda-ghalughara-massacre/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/guru-tegh-bahadur-legacy-of-faith-and-freedom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-legacy-unraveling-controversies-of-mysore-tiger/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-a-true-muslim/

- https://hinduinfopedia.com/gurukul-truths-of-hindu-wisdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/gurukul-education-system-a-journey-through-time/

Follow us:

- English YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@Hinduofficialstation

- Hindi YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@HinduinfopediaIn

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

Previous Blogs of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-from-traders-to-rulers/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-treaty-of-allahabad-1765/

Other related blogs and posts

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-rule-in-india-a-blessing-or-a-curse/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-education-system-and-its-legacy/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/islamic-influence-and-jazia-tax-in-india/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/battle-of-plassey-a-pivotal-turning-point-in-indian-history/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-arjan-dev-ji-architect-of-faith-and-martyrdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/maratha-empire-decline-consequences-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-har-rai-a-legacy-of-compassion-and-strength/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-independence-and-mutiny-in-india-1857/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indias-freedom-struggle-efforts-and-quit-india-movement-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-tyrannical-monuments-a-legacy-of-despotism/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-ascent-governance-and-policy-dynamics/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-early-life-prelude-to-power-of-criminal-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/ahmad-shah-abdali-and-the-vadda-ghalughara-massacre/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/guru-tegh-bahadur-legacy-of-faith-and-freedom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-legacy-unraveling-controversies-of-mysore-tiger/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-a-true-muslim/

- https://hinduinfopedia.com/gurukul-truths-of-hindu-wisdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/gurukul-education-system-a-journey-through-time/

Leave a Reply