Economy in British Raj: The Systematic Drain of Indian Wealth

The Greatest Economic Heist in History

Part V: Study of East India Company and Foreign rule in Bharat

Economy in British Raj: The Silent War of Extraction

The Study of East India Company and Foreign Rule in Bharat series has so far traced the transformation of foreign traders into political masters—from the Treaty of Allahabad that legalized economic control, to the Divide and Rule policy that fractured unity, to the cultural and intellectual subjugation that followed. Each stage revealed a shift in the instruments of domination—from military conquest to psychological and social engineering. This fifth installment, Economy in British Raj: The Systematic Drain of Indian Wealth, now turns to the empire’s most destructive tool—economic exploitation. It explores how governance became extraction, how fiscal policies replaced warfare, and how the world’s richest civilization was systematically impoverished through trade manipulation, land settlements, and taxation frameworks that fed Britain’s industrial rise while starving India’s villages.

This fifth chapter in the Study of East India Company and Foreign Rule in Bharat unveils the silent war of economic extraction—the hidden architecture of an empire built on systematic impoverishment. Here, profit was not the outcome of conquest but its very purpose. From the Diwani rights of Bengal in 1765 to the “Home Charges” of the early 20th century, the Economy in British Raj functioned as a machine of relentless transfer—taxation without return, trade without balance, and governance without growth.

This blog dissects that transformation: how land-revenue systems crippled Indian agriculture, how tariff manipulation destroyed indigenous industries, how currency control institutionalized theft, and how thinkers like R. C. Dutt decoded the arithmetic of empire.

What follows is not a story of natural decline but of deliberate design—the greatest economic heist in history, where India financed Britain’s rise while being reduced to poverty in its own land.

The Drain of Wealth: Quantifying the Theft

The British might have succeeded in disguising their economic plunder as governance had Indian thinkers, administrators, and later economists not exposed its true scale. By the mid-19th century, meticulous studies of trade figures, revenue records, and official budgets began revealing a pattern: India was not being governed for development but for extraction.

Early Indian economists and civil servants, drawing directly from British financial reports, demonstrated that enormous sums of Indian revenue—measured in hundreds of millions of pounds—were leaving the country every year. These were not investments or payments for imports but systematic outflows to maintain Britain’s administration, army, and empire.

Contemporary estimates showed that nearly a quarter of India’s total income was being siphoned off annually through salaries, pensions, and interest obligations to Britain. Later historians and economists would confirm that this “drain of wealth” was not a figure of speech but a measurable mechanism of global enrichment at India’s expense.

Through these findings, the illusion of benevolent empire began to shatter. The Economy in British Raj was exposed as a deliberately engineered system of depletion—an apparatus where taxation, trade, and debt served one master: the British Treasury.

The Drain of Wealth Explained

The colonial economic relationship between India and Britain was never one of trade or mutual exchange—it was one of one-sided extraction. Wealth flowed continuously from India to Britain without any compensating return. Goods, revenues, and human labor were monetized, exported, and converted into imperial capital, feeding Britain’s industrial rise while systematically impoverishing the very land that sustained it.

Economic analyses of British rule have shown that nearly one-fourth of India’s total revenue was siphoned away annually through direct and indirect mechanisms. While official data disguised this under terms like Home Charges and Public Debt Servicing, the true effect was catastrophic—an uninterrupted financial outflow that crippled internal investment and drained the economic lifeblood of Bharat.

The drain operated through multiple channels that together formed a perfect machinery of extraction:

-

Home Charges: India paid the full cost of its own subjugation. Salaries of British officials, pensions of retired officers in England, military expenditures, and even the cost of the India Office in London were charged to Indian revenues. These payments represented up to 6–7% of India’s national income during various phases of colonial rule.

-

Private Fortunes: Company officials and merchants amassed immense personal wealth through trade monopolies, coercive taxation, and insider privileges. These fortunes were remitted to Britain, financing estates, parliamentary seats, and industrial investments—the personal enrichment of empire’s administrators.

-

Trade Imbalances: Between 1835 and 1872, India’s exports exceeded its imports by over £500 million. Instead of payment, the surplus was settled through London-based accounts, meaning India’s goods were shipped, sold, and monetized abroad—without India ever receiving the proceeds.

-

Interest and Debt Payments: India was compelled to pay interest on loans raised by Britain for wars and infrastructure that primarily served imperial interests. The debt burden became a legal mechanism to justify perpetual transfer of Indian revenue.

-

Guaranteed Returns: British enterprises in India—especially railways, banks, and shipping firms—were guaranteed fixed profits, even when they operated at a loss. These profits were drawn directly from Indian taxation, ensuring that British investors faced no risk and India bore all costs.

The Significance of the Drain

The concept of the drain of wealth demolishes the colonial myth that British rule brought economic progress. Railways, telegraphs, and administration—often cited as “gifts of the empire”—were paid for entirely by Indian revenues. The so-called benefits of modernity were financed by the very victims of exploitation.

This structural drain explains the paradox that defined the Economy in British Raj: Britain’s industrial boom was the mirror image of India’s economic collapse. India was not poor because it lacked enterprise or innovation—it was impoverished because its wealth was systematically extracted and exported under legal cover. The poverty of India and the prosperity of Britain were inseparable; one existed only because of the other.

The economic mechanisms that enabled this transfer were embedded within the very revenue systems of British administration. Policies like the Permanent Settlement, Ryotwari, and Mahalwari not only exploited the peasantry but institutionalized the flow of wealth to Britain. To understand how this extraction functioned at the ground level, one must examine these systems that turned every Indian field into a revenue source for a foreign empire.

The Revenue Systems: Extracting Maximum Taxation

The foundation of British economic exploitation was their revenue systems—the mechanisms through which they extracted maximum taxation from Indian agriculture, the backbone of India’s economy. The British implemented three main revenue systems, each designed to maximize extraction while creating classes dependent on British rule.

The Permanent Settlement (1793): Creating Exploitative Landlords

Lord Cornwallis introduced the Permanent Settlement in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1793. It was a grand contract signed between the government of the East India Company in Bengal and individual landholders—zamindars and talukdars.

How It Worked:

Zamindars were required to pay 10/11th of the revenue to the Company, keeping the remaining 1/10th for themselves. This revenue demand was fixed permanently—hence “Permanent Settlement”—meaning it would never increase regardless of agricultural productivity or land values.

On paper, this seemed reasonable. In practice, it was devastating:

For Peasants: Zamindars were granted ownership of land and tasked with collecting taxes from cultivators, but a key obligation was to provide land deeds (pattas) to the farmers, which was often neglected. Peasants who had tilled land for generations suddenly became tenants with no rights. Zamindars could evict them, raise rents arbitrarily, and extract additional illegal taxes.

For Zamindars: The fixed revenue demand was set at impossibly high levels. Many zamindars couldn’t pay and lost their lands through auction. Those who survived did so by ruthlessly exploiting peasants, extracting every possible rupee to meet Company demands.

For the Company: Initially, the Company benefited from guaranteed revenues. But as agricultural productivity increased and land values rose, the fixed revenue meant the Company couldn’t capture these gains. However, this “disadvantage” to the Company was far outweighed by the political benefits.

The Political Purpose:

The Permanent Settlement created a class of zamindars whose wealth and status depended entirely on British rule. These landlords became loyal British allies, opposing any nationalist movement that threatened the system from which they profited. They provided a conservative bulwark against reform and resistance.

This pattern repeated throughout British India—economic policies designed not just for extraction but to create dependent classes with vested interests in maintaining colonial rule.

The Ryotwari System: Direct Exploitation

In Madras and Bombay Presidencies, the British implemented the Ryotwari system under Thomas Munro and Mountstuart Elphinstone. Unlike the Permanent Settlement that worked through intermediary zamindars, the Ryotwari system involved direct settlement between the government and individual cultivators (ryots).

How It Worked:

Each cultivator was recognized as the owner of their land and dealt directly with the government for revenue payments. The revenue was not permanent but periodically revised based on assessments of land productivity.

The Reality:

The revenue demands under Ryotwari were set at 50-60% of the gross produce—double the traditional rates under indigenous rulers. These extortionate demands forced cultivators into perpetual debt. When they couldn’t pay, their lands were confiscated and sold.

The periodic reassessments meant that any improvement in agricultural productivity was immediately captured by increased taxation. Cultivators had no incentive to invest in land improvement because any gains would be taxed away. This created agricultural stagnation.

The Mahalwari System: Village-Based Exploitation

In North-Western Provinces and Punjab, the British implemented the Mahalwari system, making village communities collectively responsible for revenue payment.

How It Worked:

Revenue was assessed on the entire village (mahal), and the village community was collectively responsible for payment. Village headmen collected taxes from individual cultivators and paid the total to the government.

The Reality:

Collective responsibility meant that when some cultivators couldn’t pay, others had to make up the difference or the entire village faced penalties. This created tensions within village communities and destroyed traditional cooperation systems.

The Common Pattern: Maximum Extraction, Minimum Development

Despite their differences, all three revenue systems shared common features:

Inflexible Demands: Revenue had to be paid in cash at fixed dates, regardless of crop failures, famines, or market conditions. Traditional rulers had adjusted revenue demands during hardship. The British never did.

No Investment in Agriculture: The British extracted maximum revenue but invested nothing in irrigation, agricultural improvement, or rural infrastructure. This contrasted sharply with traditional Indian rulers who had maintained irrigation systems and supported agricultural development.

Commercialization of Agriculture: To pay cash revenues, peasants had to grow cash crops (cotton, indigo, opium) instead of food crops. This destroyed food security and created vulnerability to famine.

Permanent Indebtedness: The impossibly high revenue demands forced cultivators into debt to moneylenders charging usurious interest rates. This created permanent rural indebtedness that persists to this day.

Creating Dependent Classes: Each system created classes—zamindars, moneylenders, village headmen—whose prosperity depended on the colonial system and who therefore opposed nationalist movements.

Deindustrialization: Destroying India’s Industries

If revenue extraction was the first mechanism of drain, deindustrialization was the second—and perhaps even more devastating. India in 1700 was a manufacturing powerhouse, particularly in textiles. By 1900, India had been transformed into an exporter of raw materials and importer of British manufactured goods.

India’s Pre-Colonial Industrial Strength

Before British rule, India was famous worldwide for its textiles:

- Muslin: Bengal muslin was so fine it was called “woven air”—a length of muslin could pass through a ring

- Calico: Named after Calicut, Indian cotton cloth dominated European markets

- Silk: Indian silk competed with Chinese silk in quality and craftsmanship

- Dyeing: Indian vegetable dyes produced colors that didn’t fade, unmatched anywhere

- Shipbuilding: Indian-built ships were superior to European vessels

Indian textiles dominated global trade. European merchants came to India to buy these textiles, paying in silver bullion because India produced what Europe wanted but Europe produced little that India needed.

The Systematic Destruction

The British didn’t compete with Indian industries—they destroyed them through deliberate policy:

Phase 1: Controlling Production (1770s-1810s)

After gaining control of Bengal, the Company forced weavers and artisans to sell exclusively to them at artificially low prices. Contemporary accounts describe extreme coercion of weavers—often dramatized in later narratives as “thumb-cutting.” Traditional merchant networks were destroyed. Weavers were reduced to virtual slaves, producing for Company profit.

Phase 2: Tariff Manipulation (1810s-1850s)

British textiles entering India faced minimal or no tariffs. Indian textiles entering Britain faced prohibitive tariffs of 70-80%. This made Indian textiles uncompetitive in British markets while British textiles flooded Indian markets.

The impact was catastrophic. In 1813, Indian textiles still competed globally. By 1850, India’s textile industry was decimated. The weavers of Dacca, who had produced the finest muslin in the world, were reduced to poverty or switched to agricultural labor.

Phase 3: Railway-Enabled Market Destruction (1850s-1900s)

British railways—often cited as colonial “development”—primarily served to:

- Transport raw cotton from Indian farms to ports for export to British mills

- Distribute British-manufactured textiles throughout India’s interior

- Destroy local industries that had been protected by transportation costs

The Statistics of Destruction:

- In 1750, India produced about 25% of the world’s textiles, while Britain produced less than 2%.

- By 1900, Britain’s share had risen to 25% and India’s had fallen below 2%.

- Indian textile exports, once dominant in global markets, declined from roughly 30% of world textile production to nearly zero.

- Millions of Indian weavers, spinners, and artisans lost their livelihoods

The Impact on Employment

Deindustrialization meant millions lost their traditional livelihoods. Artisans and craftspeople were forced into agricultural labor, increasing pressure on land. This contributed to:

- Fragmentation of landholdings into uneconomic units

- Increased rural poverty and indebtedness

- Greater vulnerability to famine

- Permanent unemployment and underemployment

The British claimed they were bringing “progress” through industrialization. The truth was they were destroying Indian industry to create captive markets for British manufactures.

Trade Policies: Rigged for British Benefit

Beyond direct revenue extraction and industrial destruction, British trade policies were systematically rigged to benefit Britain at India’s expense.

The Terms of Trade

Under British rule, India was forced into a trade relationship that violated basic economic principles:

Raw Material Exports: India exported raw cotton, raw jute, raw silk, indigo, opium, tea, and other primary products. These low-value exports provided minimal returns to Indian producers.

Manufactured Imports: India imported British textiles, machinery, and other manufactured goods. These high-value imports drained wealth from India while enriching British manufacturers.

Price Manipulation: The Company and later British trading firms manipulated prices, buying Indian raw materials cheap and selling British manufactures expensive.

The Opium Trade: Forced Cultivation for Imperial Profit

One of the most morally bankrupt aspects of British economic policy was the opium trade. The British forced Indian peasants to cultivate opium, which they then exported to China, using the proceeds to fund the purchase of Chinese tea for British consumption.

Indian peasants were forced to grow opium instead of food crops, receiving minimal payment. The opium was sold in China at enormous profit. When China tried to ban opium imports (recognizing the devastating social impact), Britain fought two Opium Wars to force China to accept British drug trafficking.

This triangular trade—Indian opium to China, Chinese tea to Britain, British manufactures to India—enriched Britain while devastating both India and China.

The Home Charges: Taxing India for British Benefit

Perhaps the most brazen mechanism of drain was the Home Charges—the expenses that India was forced to pay for British rule:

Military Expenses: India paid for the entire cost of the British Indian Army, including:

- Salaries of British officers

- Cost of British troops stationed in India

- Pensions of retired British military personnel

- Cost of British military campaigns fought using Indian troops (Afghanistan, Burma, China, East Africa, World War I, World War II)

Administrative Costs: India paid for:

- Salaries of British civil servants in India

- Pensions of retired British officials

- Entire cost of the India Office in London

- Personal expenses of British officials including luxurious lifestyles

Guaranteed Returns: India paid guaranteed minimum returns to British investors in:

- Railway companies (even when railways lost money)

- British banks and commercial enterprises

- Insurance and shipping companies

Debt Service: India paid interest on debts incurred by the British government—debts taken to:

- Fund British wars

- Build infrastructure serving British interests

- Compensate British investors for losses

The Home Charges represented an enormous and continuing drain—the very figures quantified earlier in Dadabhai Naoroji’s “Drain Theory” now appearing as official administrative transfers. By the early 20th century, these payments exceeded £20 million annually, drawn entirely from Indian revenues without any reciprocal economic return.

The Railway Myth: Development or Exploitation?

British apologists often cite railways as evidence that colonial rule benefited India. The reality was very different.

The Real Purpose of Indian Railways

Indian railways were not built to develop India but to serve British economic and military interests:

Economic Purpose:

- Transport raw materials from interior to ports for export

- Distribute British manufactured goods throughout India

- Destroy local industries by breaking their transportation-cost protection

- Generate guaranteed profits for British investors

Military Purpose:

- Rapidly move British troops to suppress resistance

- Control India’s interior from coastal bases

- Facilitate military campaigns in Afghanistan and Burma

Who Paid, Who Benefited?

Indians Paid Everything:

- British railway companies were guaranteed a 5% return on investment through the “Guarantee System” introduced in 1849 under Lord Dalhousie—returns paid from Indian revenues even when the railways lost money

- All construction costs came from Indian taxation

- India paid for land acquisition

- Railways were deliberately built with wide gauge incompatible with neighboring regions to prevent India’s industrial integration

British Benefited:

- Guaranteed returns for British investors—no risk, pure profit

- British companies supplied rails, engines, and equipment

- British engineers received inflated salaries

- British commerce benefited from improved transportation

The Economic Impact

Rather than sparking Indian industrialization as in other countries, railways in India:

- Drained wealth through guaranteed returns

- Destroyed local industries through cheaper transport

- Facilitated raw material export

- Created dependence on British technology and expertise

- Failed to promote indigenous industrial development

Railways were not instruments of development—they formed the backbone of Britain’s colonial extraction system. The same logic extended across all imperial infrastructure: ports, telegraphs, and irrigation canals were built primarily to move raw materials, control territories, and secure revenue channels to Britain. Whether transporting cotton and opium to coastal ports or transmitting military orders inland, every line and wire served the colonial economy, not Indian progress.

In essence, what British policy projected as modernization was in fact a coordinated logistics network designed for one purpose—the systematic transfer of India’s wealth to Britain.

The Currency Manipulation: Exchange Rate Exploitation

The British manipulated Indian currency and exchange rates to further drain wealth:

The Silver Standard

India traditionally used silver-based currency. The British forced India to remain on the silver standard even after Britain adopted the gold standard. As silver depreciated globally, India’s purchasing power declined, making Indian imports more expensive while British exports to India became cheaper.

The Home Charges in Gold

The Home Charges had to be paid in pounds sterling (gold-backed). As the silver rupee depreciated against gold, India had to pay more rupees for the same pound sterling obligations. This exchange rate manipulation represented an additional drain beyond the actual Home Charges.

Another crucial post-1858 mechanism was the Council Bill system, through which Indian revenues were remitted to Britain. The Secretary of State for India in London sold “Council Bills” to British importers, who paid in pounds; these bills were then encashed in India by exporters in rupees drawn from Indian revenue. This created a financial loop that transferred India’s export earnings directly to the British Treasury without physical movement of gold or silver. The system effectively institutionalized the drain by ensuring that even India’s trade surpluses never entered the Indian economy—they were absorbed into Britain’s balance-of-payments advantage.

Remittances and Capital Flight

British officials, merchants, and investors remitted their earnings to Britain in pounds sterling. As the rupee depreciated, they benefited from favorable exchange rates—earning rupees in India and converting to pounds at advantageous rates, increasing the real value of wealth extracted.

The Human Cost: Poverty and Underdevelopment

The systematic drain of wealth had devastating human consequences:

Declining Living Standards

Per capita income in India stagnated or declined under British rule. While Britain industrialized and living standards rose dramatically, Indian living standards remained among the world’s lowest.

Indian per capita income in 1947 was only marginally higher than in 1757—rising from roughly $550 in 1757 to about $619 in 1947 (2011 PPP terms). This minimal increase over nearly two centuries highlights India’s prolonged economic stagnation even as the world economy expanded dramatically.

Nutritional Decline

British revenue demands forced commercialization of agriculture—growing cash crops instead of food. This created permanent food insecurity. Nutritional standards declined. Famines became frequent and devastating (we’ll examine this in detail in Blog 7).

Educational Destruction

Despite collecting enormous revenues from India, the British spent almost nothing on education. In 1947, India’s literacy rate was 12%—one of the world’s lowest. The British never intended to educate Indians beyond the minimum necessary to staff lower-level administration.

Health Neglect

Public health expenditure was minimal. Life expectancy remained around 32 years. Preventable diseases killed millions. The British spent more on maintaining one British official in luxurious comfort than on the health of thousands of Indians.

Infrastructure for Exploitation, Not Development

British infrastructure—railways, ports, telegraphs—served extraction, not development:

- Railways connected raw material sources to ports, not Indian cities to each other

- Ports facilitated export of Indian resources, not Indian commerce

- Telegraphs controlled India, not connected Indians

- Irrigation focused on cash crops for export, not food security

Contrasting Pre-Colonial and Colonial Economies

Pre-Colonial Economy

Before British rule, India’s economy was characterized by:

- High manufacturing capacity, particularly textiles

- Self-sufficient agriculture with food security

- Extensive internal and external trade

- Wealth circulated within Indian economy

- Revenue supported indigenous rulers, armies, and administration

- Traditional systems managed famines and agricultural risks

Colonial Economy

Under British rule, India’s economy was transformed into:

- Exporter of raw materials, importer of manufactures

- Agriculture commercialized for cash crops, not food security

- Wealth systematically drained to Britain

- Industries destroyed to serve British manufacturers

- Revenue funded British administration, military, and guarantees to British investors

- No systems to manage economic crises—famines killed millions

The transformation was deliberate and systematic, designed to enrich Britain by impoverishing India.

R.C. Dutt and the Economic Critique

Dadabhai Naoroji wasn’t alone in documenting British economic exploitation. Romesh Chunder Dutt (1848-1909), a distinguished civil servant and economic historian, provided detailed analysis of British revenue and commercial policies.

In his books “The Economic History of India” (1901-1903), Dutt documented:

- How British land revenue policies impoverished Indian agriculture

- How trade policies destroyed Indian industries

- How taxation funded British interests, not Indian development

- How famines were caused by British economic policies, not natural disasters

Dutt’s work, combined with Naoroji’s Drain Theory, created an empirical foundation for understanding colonial economic exploitation that British apologists could not refute.

The Colonial Economic Structure: A System of Extraction

The genius of British economic exploitation was its systematic integration:

Revenue Systems extracted maximum taxation from agriculture → created dependent landlord classes → impoverished peasantry

Trade Policies destroyed Indian industries → created captive markets for British manufactures → deindustrialized India

Financial Structures (Home Charges, guaranteed returns, currency manipulation) → systematic wealth transfer to Britain → drained capital needed for Indian development

Infrastructure (railways, ports, telegraphs) → served extraction and control → facilitated drain rather than development

Political Structures (divide and rule, educated elite, military recruitment) → prevented unified resistance → maintained system despite overwhelming numerical inferiority

Each element reinforced the others, creating a self-perpetuating system of exploitation that enriched Britain while impoverishing India.

The Greatest Wealth Transfer in History

The cumulative awareness of this economic exploitation eventually ignited organized Indian responses. By the early 20th century, nationalist thinkers and industrialists invoked the Swadeshi Movement (1905) as an economic counter-revolution—urging Indians to boycott British goods and revive indigenous industries. Figures such as Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and later Mahatma Gandhi connected Naoroji’s “drain of wealth” thesis to a moral and economic call for self-reliance. Thus, the colonial economy that impoverished India also sowed the seeds of economic nationalism—a link that would mature into the freedom struggle’s demand for Purna Swaraj (complete independence).

The economy under British Raj was not a system of governance or development—it was a system of systematic wealth extraction unprecedented in scale and duration. From 1765 to 1947—182 years—Britain drained India’s wealth through every possible mechanism.

The scale of this drain was staggering. Modern economic estimates, such as those by Utsa and Prabhat Patnaik (Columbia University Press, 2022), suggest that Britain extracted the equivalent of about $45 trillion (in current dollar value) from India during colonial rule. This doesn’t include the compound interest that wealth would have earned if it had remained in India and been invested in development.

This wasn’t accidental impoverishment or the natural result of economic evolution. This was deliberate policy, implemented systematically through revenue extraction, deindustrialization, trade manipulation, financial exploitation, and infrastructural control.

Dadabhai Naoroji’s Drain Theory provided empirical documentation that could not be refuted. British apologists tried to claim they brought railways, telegraph, and modern administration. Naoroji proved that Indians paid for all of it—and paid far more than the value received, with the surplus drained to Britain.

The economic drain explains why India—one of the world’s richest civilizations for millennia—was impoverished and underdeveloped by 1947. It explains why Britain—a small island with limited natural resources—became the world’s dominant economic power. The poverty of India and the prosperity of Britain were causally linked—one created the other.

Understanding this economic dimension is essential for comprehending colonialism. Political subjugation, military control, divide and rule—all were means to an end. The end was economic extraction. Everything else served this fundamental purpose.

But the drain wasn’t only financial. Britain also physically looted India’s treasures—diamonds, gold, artwork, manuscripts, and cultural artifacts. This physical plunder, and its enduring legacy in British museums and crown jewels, is the subject of our next blog.

Screenshots Placement Summary:

1600.jpg – Pre-colonial prosperity baseline

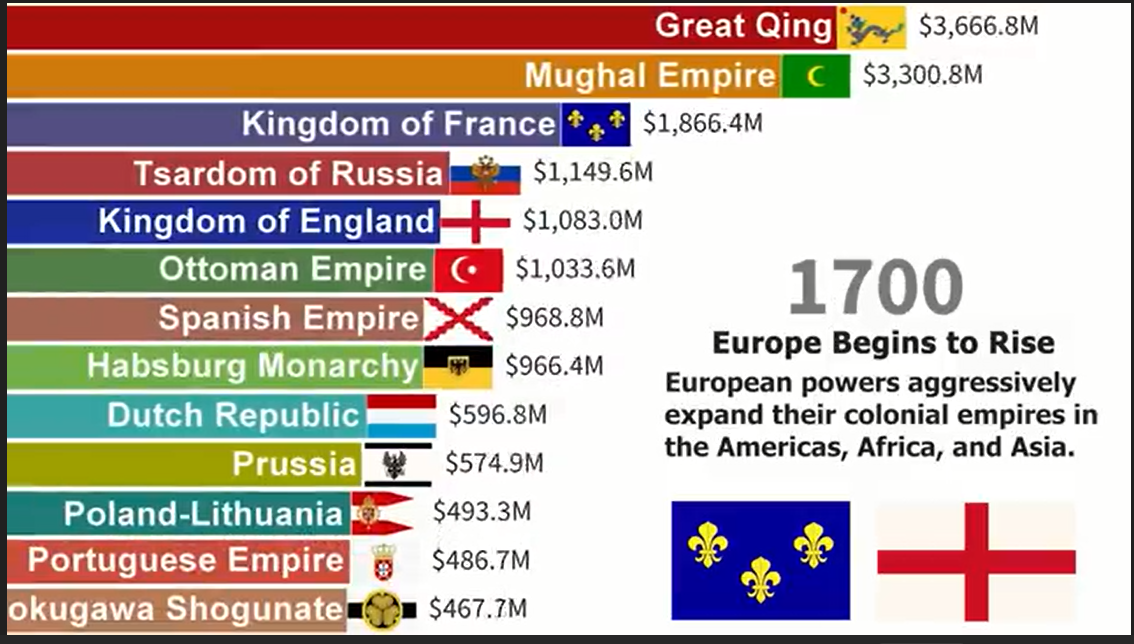

1700.jpg – India as world’s largest economy before drain began

1750.jpg – Mid-18th century manufacturing strength

1765.jpg – Treaty of Allahabad, beginning of systematic drain

1800.jpg – Early impact of drain visible

1850.jpg – Century of extraction, devastating impact

1900.jpg – Deindustrialization complete

1920.jpg – Post-WWI continued drain

1930.jpg – Depression era structural subordination

1947.jpg – Independence, showing catastrophic GDP collapse

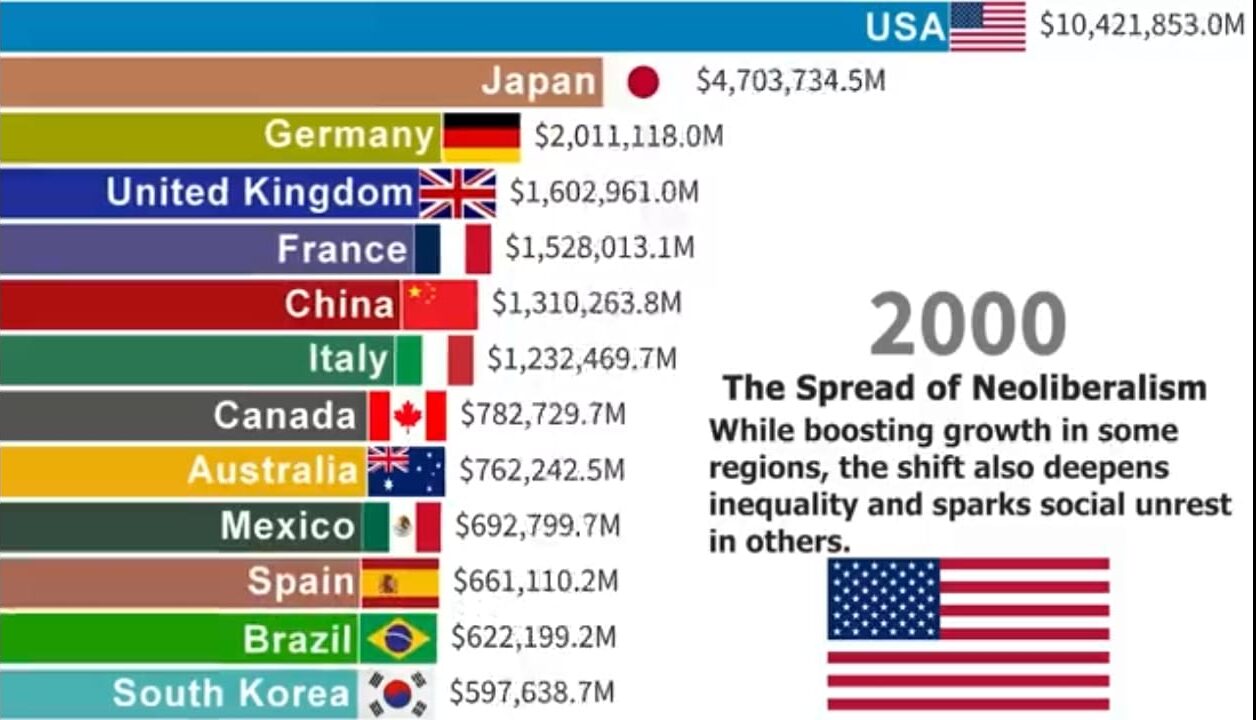

2000.jpg – Post-independence slow recovery

Each screenshot documents the progressive economic devastation caused by systematic drain, showing the direct correlation between British economic rise and Indian economic decline.

🔹Call to Action

Understanding the economic drain is crucial to grasping how colonialism systematically impoverished India while enriching Britain. This wasn’t development—it was the greatest wealth transfer in history.

Support our effort to document true history by contributing through participation and sharing.

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Watch the Videos

Glossary of Terms

-

Diwani Rights: The right to collect land revenue and administer civil justice, granted to the East India Company in 1765 after the Treaty of Allahabad — the legal start of British economic control in India.

-

Treaty of Allahabad (1765): Agreement between the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and the East India Company granting revenue collection in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

-

Home Charges: Annual payments made from Indian revenues to Britain to cover administrative costs, pensions, army expenses, and interest — a major channel of economic drain.

-

Permanent Settlement (1793): British land-revenue system in Bengal creating zamindars as landlords responsible for fixed revenue payments, often exploiting peasants.

-

Ryotwari System: Revenue arrangement in Madras and Bombay Presidencies where the government collected directly from individual cultivators (ryots), extracting up to 60 % of gross produce.

-

Mahalwari System: Revenue method in North-Western Provinces and Punjab assessing the village (mahal) collectively responsible for tax payments.

-

Council Bills: Financial instruments issued by the Secretary of State for India after 1858 to transfer Indian export earnings to Britain without moving specie — a key drain mechanism.

-

Home Civil List: British term for salaries and pensions of officials paid from Indian funds though they resided in England.

-

Deindustrialization: The deliberate destruction of India’s manufacturing, especially textiles, through discriminatory tariffs and forced raw-material export.

-

Guaranteed Returns: Profits assured to British investors in railways and enterprises from Indian revenues even when ventures failed.

-

Opium Trade: The imperial system forcing Indian peasants to grow opium for export to China — a highly profitable colonial monopoly.

-

Council of India in London: Advisory body to the Secretary of State controlling Indian finance from Britain after 1858.

-

Zamindar: Landlord under Permanent Settlement who collected tax from peasants and paid a fixed sum to the Company.

-

Ryot: Individual cultivator in British India dealing directly with colonial revenue officers under the Ryotwari System.

-

Mughal Decline: The 18th-century collapse of the Mughal Empire that enabled European trading companies to seize territorial and economic power.

-

Industrial Revolution (Britain): Period (1760–1840) of mechanized production in Britain financed in part by Indian revenues and raw materials.

-

Economic Nationalism (Swadeshi Movement 1905): Indian campaign to boycott British goods and revive indigenous industry in response to colonial extraction.

-

Drain of Wealth: The continuous outflow of India’s resources to Britain through taxation, trade imbalance, and financial remittances — the core economic mechanism of the British Raj.

#BritishRaj #ColonialDrain #IndianEconomy #WealthTransfer #HinduinfoPedia

Follow us:

- English YouTube: Hinduostation – YouTube

- Hindi YouTube: Hinduinfopedia – YouTube

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

Previous Blogs of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-from-traders-to-rulers/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-treaty-of-allahabad-1765/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-vs-maratha-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/divide-and-rule-by-east-india-company/

Other related blogs and posts

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-rule-in-india-a-blessing-or-a-curse/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-education-system-and-its-legacy/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/islamic-influence-and-jazia-tax-in-india/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/battle-of-plassey-a-pivotal-turning-point-in-indian-history/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-arjan-dev-ji-architect-of-faith-and-martyrdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/maratha-empire-decline-consequences-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-har-rai-a-legacy-of-compassion-and-strength/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-independence-and-mutiny-in-india-1857/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indias-freedom-struggle-efforts-and-quit-india-movement-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-tyrannical-monuments-a-legacy-of-despotism/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-ascent-governance-and-policy-dynamics/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-early-life-prelude-to-power-of-criminal-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/ahmad-shah-abdali-and-the-vadda-ghalughara-massacre/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/guru-tegh-bahadur-legacy-of-faith-and-freedom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-legacy-unraveling-controversies-of-mysore-tiger/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-a-true-muslim/

- https://hinduinfopedia.com/gurukul-truths-of-hindu-wisdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/gurukul-education-system-a-journey-through-time/

Leave a Reply