British Stole Indian Treasures: Colonial Plunder and Cultural Genocide

Part VI: Study of East India Company and Foreign rule in Bharat

The Theft That Never Ended

The Study of East India Company and Foreign Rule in Bharat series reveals how colonial conquest evolved from trade agreements to total domination—draining wealth, rewriting identity, and dismantling a civilization’s soul. In this sixth part, “British Stole Indian Treasures,” we uncover the story of deliberate cultural and material plunder that followed the economic drain.

Beyond the systematic exploitation documented in our previous blog, the British engaged in direct, physical looting of India’s treasures on a scale unprecedented in history. They didn’t merely tax or trade—they stole India’s cultural heritage, religious artifacts, precious gems, royal heirlooms, and sacred manuscripts, shipping them to Britain as symbols of imperial supremacy.

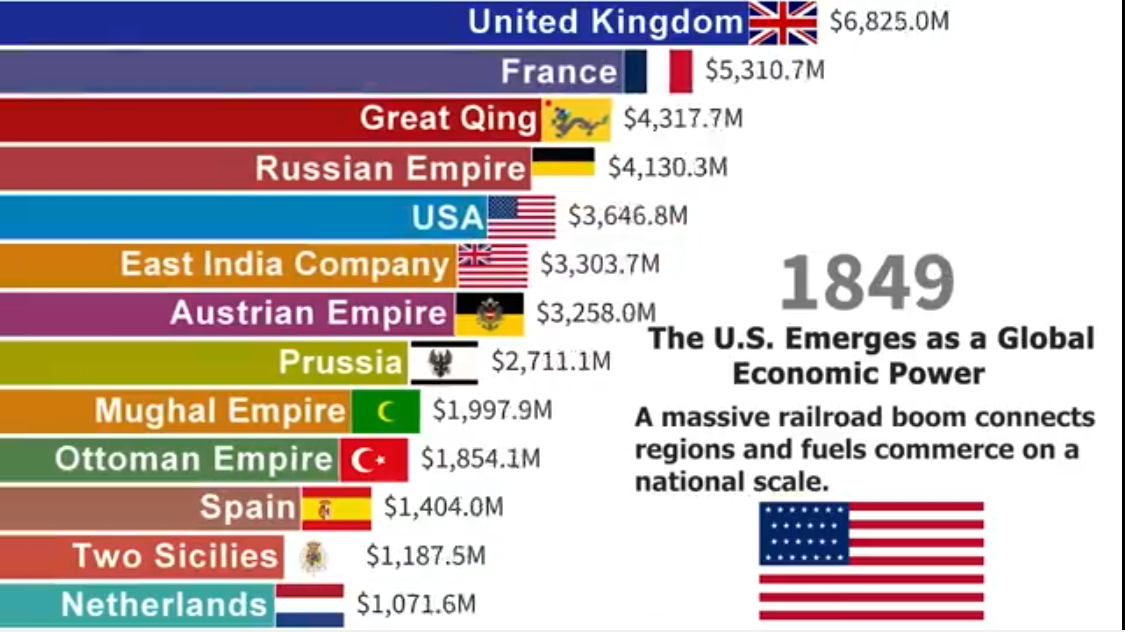

World Economy Share in 1800: The year Tipu Sultan fell at Srirangapatna, British soldiers stripped his palace of its sword, throne, jewels, and manuscripts—a pattern repeated across India, where conquest and looting marched together.

Today, the British Museum houses over 10 million artifacts, many looted from India. The Victoria and Albert Museum, National Trust properties, and even the British Crown Jewels hold treasures torn from temples and palaces. Yet when India demands their return, Britain hides behind its own laws—crafted conveniently to protect stolen property.

This blog examines that physical plunder and cultural erasure—the diamonds taken from royal vaults, the idols lifted from temples, and the manuscripts seized from libraries. It argues that this was more than theft: it was cultural genocide, a deliberate effort to erase Bharat’s civilizational memory and recast the colonized as grateful beneficiaries of “British civilization.”

The Kohinoor Diamond: Symbol of Colonial Theft

No single artifact better symbolizes British colonial plunder than the Kohinoor Diamond—one of the world’s largest and most famous diamonds, stolen from a 10-year-old Maharaja and now sitting in the British Crown Jewels.

The Diamond’s Indian History

The Kohinoor’s recorded history dates back to the 14th century, when it was owned by different ruling maharajahs and Mughals as they gained and lost power. The diamond, whose name means “Mountain of Light” in Persian, passed through various Indian dynasties—from the Kakatiyas of Warangal to the Mughals of Delhi to the rulers of Persia and Afghanistan, before returning to India with Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab.

The diamond was originally about 186 carats, and while its exact origins are unknown, it was most likely discovered in South India in the 13th century. It was an integral part of Indian royal heritage for centuries, symbolizing sovereignty and divine blessing.

How Britain Stole the Kohinoor

After the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839, Punjab descended into political instability. The British, following their established pattern, exploited this instability. After the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, they annexed Punjab and imposed the Treaty of Lahore.

The East India Company took the jewel from deposed Maharaja Duleep Singh in 1849, as a condition of the Treaty of Lahore. The treaty specified that the jewel be surrendered to Queen Victoria.

The victim was a ten-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh who was persuaded to hand over the Koh-i-Noor to Queen Victoria. “Persuaded” is a euphemism—the child was forced to surrender his kingdom’s greatest treasure as part of the terms of defeat, separated from his mother, and effectively held hostage by British officials.

The diamond originally weighed 191 carats, but it was recut to enhance its fire and brilliance in 1852 by Garrard of London, the royal jeweler. The British literally reshaped India’s treasure to suit European tastes, reducing its weight to 105.6 carats—destroying its original form forever.

The “Gift” Lie

When confronted with demands for the Kohinoor’s return, British authorities have claimed it was a “gift” to Queen Victoria. This is historical revisionism at its most brazen. A treaty imposed on a defeated kingdom, forcing a child ruler to surrender his nation’s greatest treasure to the conquerors, is not a “gift”—it is theft legitimized through legal documents.

In 2016, India’s solicitor-general controversially stated the stone was “neither stolen nor forcibly taken,” but had been “gifted” to the East India Company by the former rulers of Punjab in 1849. This statement sparked outrage in India, as it legitimized colonial theft through forced treaties.

Why Britain Won’t Return It

Upon India’s independence in 1947, the government asked for the diamond back. Britain has consistently refused. The reasons are revealing:

Legal Excuses: British law prohibits the British Museum and other institutions from “deaccessioning” objects from their collections—a law conveniently crafted to prevent returning stolen property.

Precedent Fears: If Britain returns the Kohinoor to India, it would establish precedent for returning countless other stolen artifacts to Greece, Egypt, Nigeria, and other former colonies. British museums would be emptied of their “treasures.”

Imperial Pride: The Kohinoor in the Crown Jewels symbolizes British imperial glory. Returning it would be admitting that the Empire was built on theft, not legitimate rule.

Multiple Claims: Britain cynically notes that India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran all claim the diamond, making return “complicated.” This ignores that these territorial divisions were themselves created by British colonialism.

Part of the British crown jewels since 1849, the Koh-i-noor is claimed by several countries, including India, which has demanded its return. The diamond remains in the Tower of London, a permanent symbol of colonial plunder displayed as if it were legitimate British property.

The Sack of Srirangapatna: Looting Tipu Sultan’s Kingdom

The fall of Srirangapatna in 1799 provides a detailed case study of British looting practices. When Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore, fell defending his capital, British forces didn’t just defeat him—they systematically plundered his kingdom.

The Systematic Looting

After the fall of Srirangapatna, British soldiers looted and pillaged objects from Tipu’s dead body and kingdom: his sword, jewelry, gold coins, arms and ammunition, fine clothes, and Quran.

The looting was methodical and comprehensive:

Personal Items: Tipu’s personal sword, considered one of the finest weapons ever crafted, was taken from his body. His rings, including those worn when he died, were stolen. Even his personal Quran was looted.

Royal Treasury: The entire treasury of Mysore—gold, silver, precious stones, jewelry accumulated over generations—was seized as “prize money” and distributed among British officers and soldiers.

Palace Artifacts: Furniture, artwork, weapons, astronomical instruments, manuscripts—everything of value was systematically removed from Tipu’s palace.

Temple Treasures: British forces looted temples allied with Tipu, stealing religious artifacts, gold ornaments, and sacred objects.

Where Tipu’s Treasures Are Now

Today, Tipu Sultan’s stolen treasures are scattered across British institutions:

British Museum: Contains numerous artifacts from Tipu’s kingdom, including Tipu Sultan’s Sword and Ring: Looted after the fall of Srirangapatna in 1799.

Victoria and Albert Museum: Holds Tipu’s mechanical tiger automaton—a wooden sculpture showing a tiger mauling a British soldier, which the British found so symbolically threatening they kept it as a trophy.

Windsor Castle: The royal collection contains items from Tipu’s palace, displayed as conquest trophies.

Private Collections: Many items were taken by individual British officers and remain in their descendants’ private collections.

Items from Tipu’s collection have appeared at auctions, with the UK government imposing export bars to prevent their return to India, their country of origin. A finial stayed out of public view for almost two centuries, before it was rediscovered and sold at a Bonhams auction in 2009 for £389,600. The UK imposed an export ban then as well.

The British won’t allow these treasures to leave Britain even when private owners want to sell them, but also won’t return them to India. They remain stolen property, held hostage by export bans.

British Museum: A Monument to Colonial Theft

The British Museum, founded in 1753, claims to be a universal museum preserving world heritage. In reality, it’s a repository of stolen artifacts from colonized nations. The Indian collection alone is staggering—tens of thousands of objects stolen over two centuries of colonial rule.

Major Looted Indian Artifacts

Religious Sculptures: The Amravati Marbles are Buddhist sculptures, along with a statue of the goddess of wisdom and learning from Tamil Nadu. These sacred objects were torn from their religious contexts and displayed as art objects in a foreign museum.

Temple Artifacts: Countless statues, religious icons, and architectural elements were removed from Hindu and Buddhist temples across India. Sculptures of deities that had been objects of worship for centuries became museum displays.

Hoysala Statues: Intricate sculptures from 11th-13th century Hoysala temples, representing pinnacles of Indian artistic achievement, were systematically removed and shipped to Britain.

Manuscripts and Books: Ancient Sanskrit manuscripts, Buddhist texts, Jain scriptures, and Islamic manuscripts were removed from libraries and religious institutions across India.

Coins and Seals: Thousands of historical coins and seals documenting India’s economic and political history were taken to Britain.

Jewelry and Decorative Arts: Royal jewelry, ornamental weapons, decorative textiles—anything of artistic or material value was fair game for British collectors.

The British Museum’s Refusal to Return

The British Museum has specifically said that it has no plans to repatriate stolen artifacts. Their justifications are revealing:

“World Heritage” Argument: They claim Indian artifacts are “world heritage” better preserved in British museums than in their countries of origin. This paternalistic racism assumes Indians can’t care for their own heritage.

“Educational Value” Argument: They claim displaying stolen artifacts “educates” British visitors. This ignores that these objects have greater educational and cultural value in their original contexts.

Legal Shields: The British Museum Act 1963 prohibits removing objects from the collection except in very limited circumstances. Britain literally passed laws to prevent returning stolen property.

“Better Care” Argument: They claim Indian artifacts are better preserved in climate-controlled British museums. This ignores that these artifacts survived for centuries or millennia in India before British theft.

Other British Institutions

Beyond the British Museum, numerous British institutions hold looted Indian treasures:

Victoria and Albert Museum: Holds extensive collections of Indian textiles, jewelry, weapons, and decorative arts. The Tipoo’s Tiger, the Sultan’s sword, and countless other artifacts remain on display.

National Trust Properties: British aristocrats who made fortunes in India filled their country estates with looted treasures. These remain displayed as family heirlooms rather than acknowledged as stolen property.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford: Contains significant Indian collections looted by British officials and donated to the university.

Royal Collections: The British royal family’s personal collection contains numerous Indian treasures, including items from Tipu Sultan, Mughal emperors, and various Maharajas.

The Looting Patterns: How Treasures Were Stolen

British looting followed consistent patterns across different periods and regions:

Post-Battle Plunder

After every military victory, British forces systematically looted the defeated territories:

1757 – Plassey: After defeating Siraj-ud-Daulah, British forces looted Murshidabad, the capital of Bengal. The Nawab’s treasury, palace treasures, and personal jewelry were seized.

1799 – Srirangapatna: As documented above, Tipu Sultan’s entire kingdom was systematically plundered.

1857 – Delhi and Lucknow: After crushing the 1857 rebellion, British forces engaged in systematic looting as “punishment.” The Red Fort in Delhi, the palaces of Lucknow—both were stripped of treasures accumulated over centuries.

1849 – Lahore: The annexation of Punjab involved systematic looting of the Sikh treasury, including the Kohinoor and numerous other treasures.

“Archaeological” Excavations

British “archaeologists” systematically removed artifacts from archaeological sites:

Buddhist Sites: Amaravati, Sanchi, and other Buddhist sites were excavated, with the best sculptures and artifacts shipped to British museums.

Temple Architecture: Architectural elements, sculptures, and decorative pieces were removed from standing temples, justified as “preservation.”

Historical Sites: Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and other Indus Valley sites were excavated, with artifacts removed to British institutions.

This wasn’t archaeology—it was legal plunder, using scientific justification to legitimize theft.

“Gifts” from Subordinate Rulers

British officials extracted “gifts” from Indian rulers under their control:

Subsidiary Alliance Princes: Rulers who accepted subsidiary alliances were pressured to present valuable gifts to British officials and the Crown.

Coerced Donations: Indian princes, knowing their positions depended on British goodwill, competed to offer lavish gifts—essentially bribes for protection.

Inheritance Manipulation: When Indian rulers died without British-approved heirs, the British seized their treasuries under the Doctrine of Lapse, claiming the state and its treasures for the Company.

Individual British Officials’ Collections

British officials made personal fortunes looting India:

Warren Hastings: Returned to Britain with enormous wealth and art collections extracted from Bengal.

Robert Clive: Made a massive fortune in Bengal, some of which was used to acquire Indian treasures.

Lord Elgin: Served as Viceroy and amassed significant collections of Indian art.

Countless Others: Every British official, from governors to district collectors, acquired Indian artifacts—purchased at artificially low prices from impoverished Indians or simply taken.

The Manuscripts: Stealing India’s Intellectual Heritage

Beyond physical treasures, the British systematically looted India’s intellectual heritage—ancient manuscripts containing invaluable knowledge.

Sanskrit Manuscripts

Ancient Sanskrit texts on philosophy, science, mathematics, medicine, and literature were removed from temples, monasteries, and libraries across India. Many ended up in British libraries, catalogued but inaccessible to Indian scholars.

The Bodleian Library at Oxford, the British Library, and Cambridge University libraries hold thousands of Sanskrit manuscripts—some unique copies of texts no longer available in India.

Persian and Arabic Manuscripts

Mughal-era manuscripts in Persian and Arabic, including historical chronicles, scientific treatises, and literary works, were systematically collected and removed to Britain.

Regional Language Manuscripts

Palm leaf manuscripts in Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, and other regional languages were taken from South Indian temples and institutions.

The Impact

This intellectual theft had lasting consequences:

Loss of Knowledge: Some manuscripts have never been properly studied or translated, representing permanent loss of ancient knowledge.

Broken Traditions: Removal of texts broke continuity of traditional learning systems that had depended on these manuscripts.

Colonial Knowledge Control: British control over Indian manuscripts allowed them to control narratives about Indian history, science, and culture.

Contemporary Scholarship Obstacles: Even today, Indian scholars must travel to British institutions to access manuscripts about their own heritage.

Temple Desecration and Theft

Perhaps the most offensive aspect of British looting was the desecration of sacred sites and theft of religious objects.

Hindu Temples

British soldiers and officials systematically looted Hindu temples:

Sculptural Theft: Statues of deities, decorative elements, and architectural pieces were removed from temples and shipped to museums or sold to collectors.

Gold and Jewelry: Temple treasuries containing gold, silver, and precious stones were seized. Religious jewelry adorning deity statues was stolen.

Sacred Objects: Items used in religious ceremonies—bells, lamps, ritual objects—were taken as curiosities or souvenirs.

Buddhist Sites

Buddhist stupas and monasteries faced systematic looting:

Amaravati: The great Buddhist stupa at Amaravati in Andhra Pradesh was systematically dismantled. The British Museum’s “Amaravati Marbles” represent one of the most significant acts of cultural vandalism in history.

Sanchi: Though the main stupa survived, numerous artifacts and sculptures were removed.

Taxila and Gandhara: Buddhist sites in present-day Pakistan were excavated and their treasures shipped to British museums.

The Religious Offense

For Hindus and Buddhists, these weren’t merely artifacts—they were sacred objects, some worshipped for centuries. Their removal was religious desecration, comparable to destroying churches and stealing religious icons. Yet the British displayed them as “art” with no acknowledgment of their sacred significance.

The Textiles: Stealing India’s Craftsmanship

India was world-famous for its textiles—fine muslins, intricate brocades, vibrant prints. The British didn’t just destroy the textile industry economically (as detailed in Blog 5)—they also physically stole examples of India’s finest textile craftsmanship.

Royal Textiles

Elaborate garments worn by Mughal emperors, royal carpets, ceremonial cloths—all were looted and now fill British museums and private collections.

The Victoria and Albert Museum holds one of the world’s largest collections of Indian textiles, most acquired during colonial rule through purchase at exploitative prices or outright theft.

Craft Samples

British merchants and officials collected samples of Indian textile techniques—weaving patterns, dyeing methods, embroidery styles. These were studied to replicate in British mills, stealing not just products but production knowledge.

The Legal Theft: Doctrine of Lapse

While direct military looting was common, the British also developed legal mechanisms for theft:

Lord Dalhousie’s Doctrine of Lapse

Under this policy, if an Indian ruler died without a natural heir, the British refused to recognize adopted heirs (standard practice in Hindu tradition) and annexed the state. This meant:

State Treasuries: The entire treasury became British property.

Royal Collections: Artwork, jewelry, historical artifacts—everything became British.

Religious Endowments: Even religious properties and temple treasures were seized.

States annexed under this doctrine included Satara, Jaipur, Sambhalpur, Nagpur, and Jhansi. In each case, the British seized not just political control but all movable wealth and treasures.

The Repatriation Debate: Britain’s Continued Refusal

In recent decades, there have been increasing calls for Britain to return stolen artifacts. Britain’s responses reveal the continuing colonial mentality:

Legal Obstacles

Britain has crafted laws specifically to prevent returning stolen property:

British Museum Act 1963: Prohibits the British Museum from disposing of objects except in very limited circumstances.

Export Controls: When stolen items appear in private collections, Britain imposes export bans to prevent their return to countries of origin.

Statute of Limitations: Britain claims that theft occurring over 50 years ago cannot be legally challenged—conveniently protecting all colonial-era looting.

Spurious Arguments

When legal obstacles aren’t sufficient, Britain makes spurious arguments:

“Universal Heritage”: Claiming Indian artifacts are better displayed in British museums where “everyone” can see them. This assumes British convenience is more important than Indian cultural rights.

“Better Preservation”: Claiming British museums can better preserve artifacts than Indian institutions. This patronizing racism ignores India’s sophisticated museum systems and thousands of years of successfully preserving its heritage.

“Educational Value”: Claiming British schoolchildren benefit from seeing stolen Indian artifacts. This ignores that Indian children have greater right to access their own heritage.

“Complicated Provenance”: Claiming it’s “unclear” how artifacts were acquired. This deliberate ignorance ignores extensive documentation of colonial looting.

Rare Returns

In rare cases, Britain has returned looted items:

Netherlands Example: The Netherlands has begun returning colonial-era looted artifacts, demonstrating it’s legally and practically possible.

Recent British Museum Returns: The British Museum has returned some items illegally taken from Iraq during the 2003 invasion, proving it can return stolen property when politically convenient.

The selective returns reveal that Britain’s refusal to return Indian artifacts isn’t about legal impossibility—it’s about political unwillingness.

Calculating the Value: Trillions in Stolen Wealth

Quantifying the value of stolen treasures is difficult but important:

Material Value

The Kohinoor alone is priceless—estimates suggest it could be worth $10-12 billion in today’s market. The gold, silver, and precious stones stolen from royal treasuries and temples over two centuries would be worth hundreds of billions of dollars today.

Artistic and Historical Value

Priceless artifacts like Tipu Sultan’s sword, Mughal-era paintings, ancient sculptures, and rare manuscripts have cultural value far exceeding their material worth. These are irreplaceable pieces of human heritage.

Compound Interest

If we calculate compound interest on the material value of stolen treasures from when they were stolen, the amounts become astronomical—easily reaching into trillions of dollars.

Cultural Loss

Beyond financial calculations, there’s incalculable cultural loss:

Broken Heritage Links: Artifacts removed from their cultural contexts lose much of their meaning and significance.

Stolen Memory: Each stolen artifact represents stolen collective memory, severing contemporary Indians from their heritage.

Tourist Revenue: Treasures that should attract tourists to India instead draw them to British museums, representing ongoing economic loss.

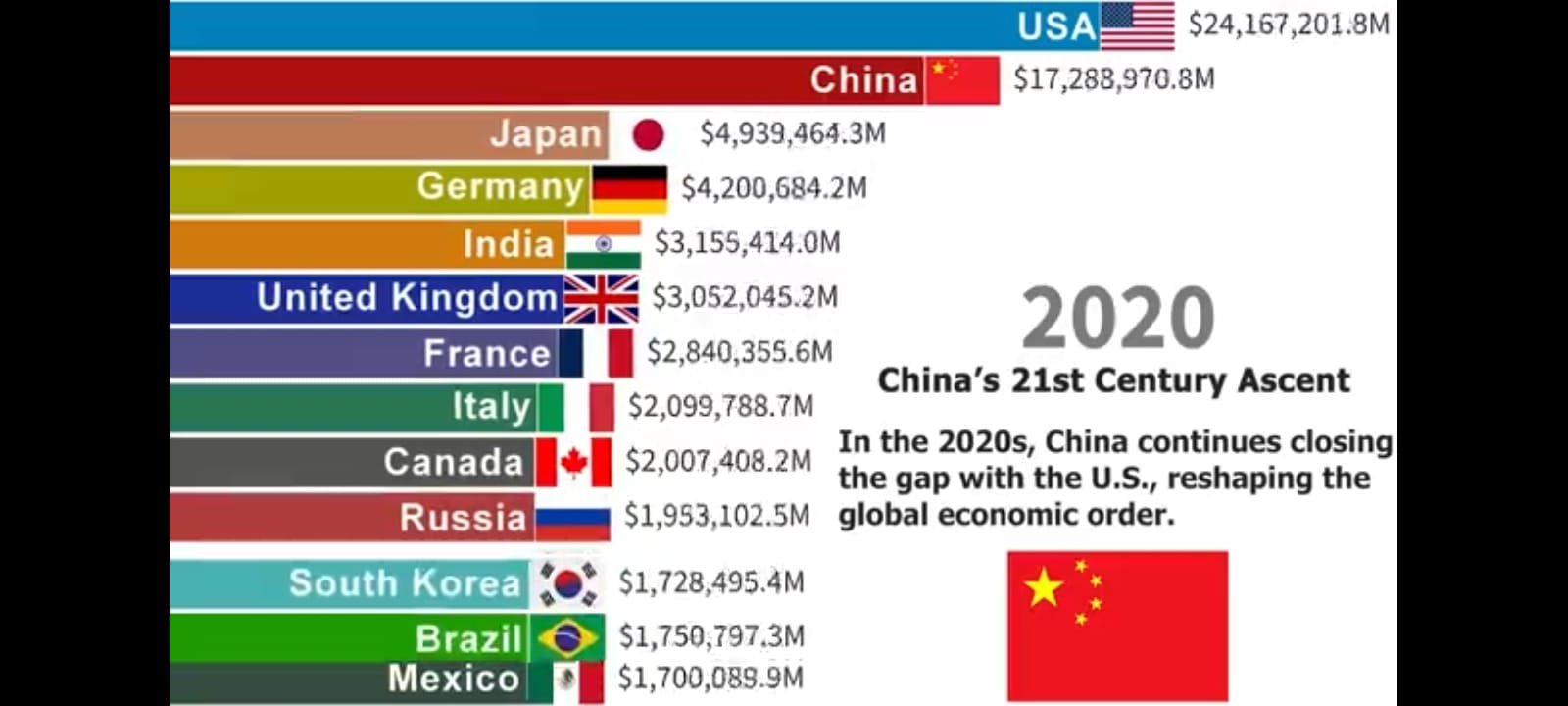

2000.jpg – World Economy Share in 2000: More than half a century after independence, India is recovering economically but its cultural treasures remain hostage in British institutions. The physical theft of heritage continues to symbolize colonial injustice and Britain’s refusal to acknowledge historical wrongs.

The Ongoing Crime: Why This Matters Today

Some argue that colonial-era theft is “history” and shouldn’t affect contemporary relations. This argument fails for several reasons:

Continuing Possession is Continuing Crime

Theft isn’t just the moment of taking—it’s the continuing possession of stolen property. Every day Britain refuses to return looted artifacts, it commits theft anew.

Symbol of Unresolved Colonial Injustice

Stolen treasures in British museums symbolize Britain’s refusal to acknowledge colonial crimes. They represent continuing colonialism—physical possession of property taken through violence.

Cultural Rights

India and Indians have inherent rights to their cultural heritage. Just as individuals have rights to family heirlooms, nations have rights to national treasures. British museums are holding hostage items that rightfully belong to India.

Precedent for Global Justice

If Britain can keep colonial loot with impunity, what message does this send? That might makes right? That theft is legitimate if you can hold onto stolen goods long enough? Returning looted artifacts would establish precedent for global justice.

Economic Justice

The treasures sitting in British museums represent wealth stolen from India—wealth that could today fund museums, schools, hospitals in India. Their return would be partial compensation for colonial economic devastation.

India’s Response: Inadequate Pursuit of Stolen Heritage

While other nations have aggressively pursued the return of looted artifacts, India’s efforts have been inconsistent:

Limited Official Efforts

The National Trust has never received a request from India for return of treasures held in British collections. This suggests India hasn’t systematically pursued repatriation.

Occasional Diplomatic Mentions

Indian governments occasionally mention artifact returns in diplomatic contexts but rarely make it a priority.

Legal Challenges

India has rarely pursued legal challenges to recover stolen property, perhaps recognizing the legal obstacles Britain has erected.

Why the Weak Response?

Several factors explain India’s inadequate pursuit:

Post-Colonial Elite Mentality: English-educated Indian elites often share British attitudes toward “universal heritage” and museum preservation.

Diplomatic Priorities: India prioritizes trade, investment, and strategic relations with Britain over historical justice.

Legal Pessimism: Recognition that British laws make legal recovery nearly impossible.

Resource Constraints: Limited resources for costly international legal battles.

However, this weak response doesn’t diminish the injustice of theft or legitimize Britain’s continued possession.

Theft That Defines Empire

The British didn’t just rule India — they extracted its soul. They stole the Kohinoor from a child ruler, looted Tipu Sultan’s treasures from his fallen body, desecrated temples, and seized sacred manuscripts. Every conquest was followed by a ledger entry, every shrine by a shipment. The so-called “civilizing mission” was in truth a campaign of organized plunder.

Today, the same stolen artifacts adorn British museums and royal collections — not as confessions of crime, but as trophies of conquest. The Kohinoor glittering in the Crown Jewels and Tipu’s Tiger caged in the Victoria and Albert Museum stand as silent witnesses to empire built on theft.

This theft that defined empire was more than material — it was civilizational. It sought to erase Bharat’s memory, fracture her continuity, and rebrand her wisdom as Western discovery. It was, in every sense, cultural genocide — the destruction of knowledge, pride, and identity that once made India the world’s teacher.

Yet the plunder of temples and treasures was only one chapter in the saga of exploitation. The same empire that emptied India’s vaults also emptied her granaries. Its economic policies forced farmers to grow cotton and indigo instead of food, creating famines that killed tens of millions. This systematic, policy-driven annihilation of life — the famine genocide — forms the subject of our next blog.

🔹Call to Action

The theft of India’s cultural heritage is an ongoing crime. Britain continues to possess stolen property and refuses to acknowledge historical injustice. Understanding this theft is crucial to demanding justice.

Support our effort to document colonial crimes by sharing this series and contributing to this project.

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Watch the Videos

Glossary of Terms

-

Doctrine of Lapse: A policy introduced by Lord Dalhousie allowing the British East India Company to annex Indian states whose rulers died without a male heir.

-

East India Company: A British trading corporation that gradually conquered large parts of India between 1600 and 1858.

-

Kohinoor Diamond: India’s legendary 186-carat diamond taken from 10-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh under the 1849 Treaty of Lahore.

-

Treaty of Lahore: 1849 agreement that annexed Punjab to British India and formally transferred the Kohinoor to Queen Victoria.

-

Srirangapatna: Capital of Mysore ruled by Tipu Sultan; sacked and looted by British forces in 1799.

-

Tipu Sultan’s Tiger: A mechanical automaton depicting a tiger mauling a British soldier—taken from Tipu’s palace and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

-

Amaravati Marbles: 2nd-century BCE Buddhist sculptures from Andhra Pradesh removed to the British Museum in the 19th century.

-

Bodleian Library: Oxford University’s ancient repository holding thousands of Sanskrit and regional manuscripts taken from India.

-

Cultural Genocide: The deliberate destruction of a people’s cultural, intellectual, and spiritual foundations without physical extermination.

-

British Museum Act 1963: UK law preventing the British Museum from returning objects in its collection—effectively legalizing retention of colonial loot.

-

Maddison Project: Global economic history research estimating long-term GDP shares of nations; data show India’s collapse under colonialism.

-

Utsa Patnaik: Indian economist whose research estimated Britain drained ≈ US $45 trillion from India between 1765–1938.

-

Dadabhai Naoroji: Early Indian nationalist who formulated the “Drain Theory,” exposing Britain’s economic exploitation of India.

-

World Economy Share: India’s approximate percentage of global GDP at different historical points, illustrating decline under British rule.

-

British Crown Jewels: The ceremonial regalia of the UK monarchy that includes the stolen Kohinoor Diamond.

-

Victoria and Albert Museum: London museum holding vast collections of Indian art and textiles taken during colonial rule.

-

Benin Bronzes: Nigerian artworks looted by Britain in 1897; modern restitution cases set precedent for returning colonial artifacts.

-

Asante Gold Regalia: Royal treasures of Ghana’s Asante Kingdom, partially returned by UK museums in 2024.

-

Indigo and Opium Monoculture: Cash-crop systems imposed by the British that displaced food farming and deepened colonial famines.

-

Mike Davis: Historian and author of Late Victorian Holocausts analyzing British imperial policies behind 19th-century Indian famines.

#ColonialLoot #Kohinoor #CulturalGenocide #BritishEmpire #HinduinfoPedia

Follow us:

- English YouTube: Hinduostation – YouTube

- Hindi YouTube: Hinduinfopedia – YouTube

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

Previous Blogs of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-from-traders-to-rulers/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-treaty-of-allahabad-1765/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-vs-maratha-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/divide-and-rule-by-east-india-company/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/economy-in-british-raj-the-systematic-drain-of-indian-wealth/

Other related blogs and posts

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-rule-in-india-a-blessing-or-a-curse/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-education-system-and-its-legacy/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/islamic-influence-and-jazia-tax-in-india/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/battle-of-plassey-a-pivotal-turning-point-in-indian-history/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-arjan-dev-ji-architect-of-faith-and-martyrdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/maratha-empire-decline-consequences-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-har-rai-a-legacy-of-compassion-and-strength/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-independence-and-mutiny-in-india-1857/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indias-freedom-struggle-efforts-and-quit-india-movement-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-tyrannical-monuments-a-legacy-of-despotism/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-ascent-governance-and-policy-dynamics/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-early-life-prelude-to-power-of-criminal-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/ahmad-shah-abdali-and-the-vadda-ghalughara-massacre/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/guru-tegh-bahadur-legacy-of-faith-and-freedom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-legacy-unraveling-controversies-of-mysore-tiger/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-a-true-muslim/

- https://hinduinfopedia.com/gurukul-truths-of-hindu-wisdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/gurukul-education-system-a-journey-through-time/

Leave a Reply