Bengal Famine and British Genocides: How Colonial Policies Killed Millions

Part VII: Study of East India Company and Foreign rule in Bharat

Bengal Famine and British Role: Was it Genocides?

The story of Bengal Famine and British rule is not just about starvation—it is about a system that turned hunger into policy. Between 1765 and 1947, India suffered twelve major famines, claiming an estimated 30 to 60 million lives. These were not random natural calamities but deliberate outcomes of economic extraction, administrative rigidity, and moral indifference. The British empire built its wealth on India’s hunger, and the price was paid in human lives.

This blog continues the exploration of how British colonial policies transformed India’s economy, society, and moral fabric. The earlier parts of this series examined how the East India Company’s “Drain of Wealth” dismantled India’s economic foundations, how cultural plunder and manuscript looting erased intellectual traditions, and how divide-and-rule politics fractured a once-unified society. This chapter turns to the most devastating legacy of all — the famines that revealed the human cost of empire.

From the Great Bengal Famine of 1770, where ten million died just five years after the Treaty of Allahabad, to the Bengal Famine of 1943 under Winston Churchill that killed over three million, each tragedy followed a pattern — taxation in times of scarcity, export of food from starving provinces, and suppression of private charity. These were not errors of judgment; they were expressions of a worldview that valued imperial revenue above Indian life.

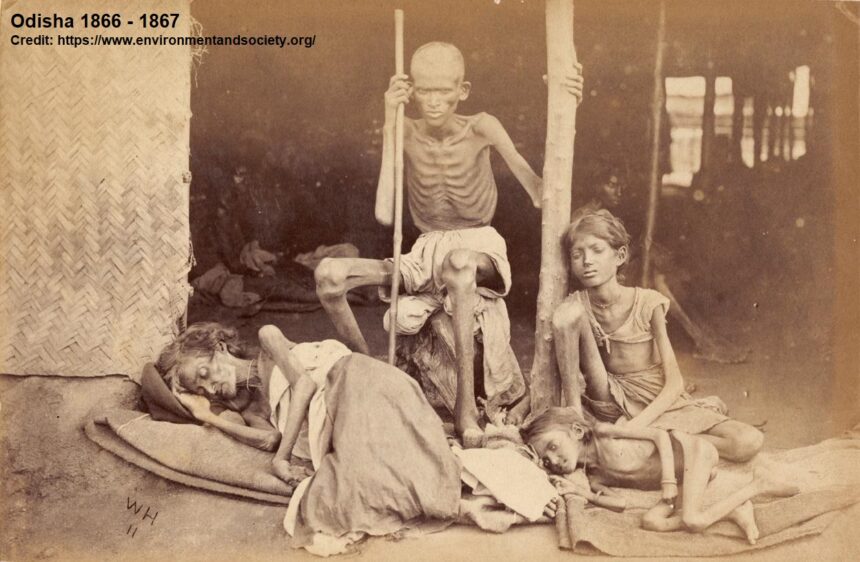

Through documented famines — Chalisa (1783–84), Doji Bara (1791–92), Orissa (1866–67), Deccan (1876–78), and Bengal (1943) — this blog traces how colonial policies institutionalized famine. It also contrasts British negligence with India’s earlier dharmic governance, where rulers opened granaries, remitted taxes, and treated famine relief as sacred duty.

Understanding the Bengal Famine and British policy is vital not merely to recount suffering, but to expose how economics was weaponized as governance. The pattern reveals a chilling truth — that for the empire, Indians were expendable resources, not citizens. Their deaths were not collateral damage; they were calculated costs of profit and power.

The Great Bengal Famine of 1770: First Consequence of Company Rule

The Great Bengal Famine of 1770 holds terrible historical significance—it was the first major consequence of the East India Company’s acquisition of Diwani rights through the Treaty of Allahabad just five years earlier. The famine killed approximately 10 million people—one-third of Bengal’s population—making it one of the deadliest famines in human history.

As one witness put it during that summer, “I could have purchased a thousand children … for three rupees”—a ghastly market born of hunger. (1770 testimony compiled in this contemporary account; see the classic synthesis in Hunter, 1868).

The Context: Five Years of Company Exploitation

When the Company gained Diwani rights in 1765, they immediately set about maximizing revenue extraction. The Dual System—where the Company controlled revenue collection while the Nawab nominally retained administrative responsibility—created a perfect recipe for disaster.

Company officials focused solely on extracting maximum revenues with no concern for agricultural sustainability or population welfare. The fixed revenue demands were set impossibly high—approximately 50% higher than under previous Mughal administration. These demands had to be paid in cash at fixed dates regardless of crop conditions or market prices.

The Drought and the British Response

In 1769, the monsoon failed in Bengal, leading to crop failures. This was not unprecedented—droughts had occurred before. What made 1770 catastrophic was the British response, or rather, the lack of any humane response.

Traditional Indian rulers had established systems for famine relief:

- Opening state granaries to distribute grain

- Remitting or postponing revenue demands

- Organizing public works to provide employment

- Preventing grain hoarding and speculation

- Restricting exports during shortages

The East India Company did none of these things. Instead:

What the Company knew (and still prioritised revenue): Contemporary officials and critics left stark records. In Annals of Rural Bengal, civil servant William Wilson Hunter describes how, “All through the stifling summer of 1770 the people went on dying… they devoured their seed-grain; they sold their sons and daughters, till at length no buyer of children could be found.” (Hunter, 1868, Annals of Rural Bengal, p.26) Even earlier, East India Company insider-turned-whistleblower William Bolts condemned Company revenue demands during scarcity in 1772 in Considerations on India Affairs, a detailed indictment of Bengal governance immediately after the famine. These sources show officials were informed of mass starvation yet did not relax revenue extraction or maintain public granaries, setting a pattern that recurred for decades.

Inflexible Revenue Demands: Despite the drought and crop failures, Company officials continued demanding full revenue payments. Peasants were forced to sell their seed grain, farming implements, and even household goods to meet tax obligations.

No Relief Measures: The Company maintained no granaries for famine relief. When people began starving, no systematic relief was provided. The Dual System meant the Company claimed they were only responsible for revenue collection, not administration—a convenient excuse to avoid responsibility for the catastrophe their policies created.

Continued Exports: Even as millions starved, grain exports from Bengal continued. The Company prioritized export profits over feeding starving Indians. Ships loaded with Bengali grain sailed to foreign markets while Bengalis died of starvation in the streets.

Hoarding and Speculation: Company officials and their associates hoarded grain, driving up prices to maximize profits. The free market in grain, which might have brought supplies from other regions, was disrupted by Company monopolies and speculation.

The Death Toll

The famine lasted from 1769 to 1773, with 1770 being the worst year. Estimates suggest 10 million people died—approximately one-third of Bengal’s population. Entire villages were depopulated. The streets of Calcutta (now Kolkata) were filled with corpses. Contemporary accounts describe horrific scenes of starvation, with people reduced to eating grass, tree bark, and even their own children.

The British historian William Wilson Hunter, writing in the 1870s, described the famine: “All through the stifling summer of 1770 the people went on dying. The husbandmen sold their cattle; they sold their implements of agriculture; they devoured their seed-grain; they sold their sons and daughters, till at length no buyer of children could be found; they ate the leaves of trees and the grass of the field.”

The Company’s “Solution”

The Company’s response to the famine was not to reduce revenue demands or provide relief. Instead, they increased revenue demands on the surviving population to make up for the “revenue losses” caused by the deaths of taxpayers. The callousness is breathtaking—millions died, and the Company’s concern was maintaining revenue levels, not preventing future catastrophes.

The famine did lead to some administrative changes. Warren Hastings ended the Dual System in 1772, bringing Bengal under direct Company administration. But this reform was about improving revenue collection efficiency, not about protecting the population from future famines. The fundamental priority—extracting maximum wealth from India for British benefit—remained unchanged.

The Long-Term Impact

The Great Bengal Famine of 1770 had lasting consequences:

Demographic Catastrophe: Bengal lost one-third of its population. This demographic shock took generations to recover from.

Agricultural Collapse: With millions dead, vast tracts of previously cultivated land went fallow. Agricultural productivity collapsed.

Economic Devastation: Bengal’s famous textile industry, already under pressure from Company policies, suffered further as weavers and artisans died or fled.

Social Breakdown: The famine destroyed traditional village communities, displaced populations, and created lasting trauma.

Most significantly, the famine established a pattern that would repeat throughout British rule: when economic extraction conflicted with Indian lives, British officials always chose extraction. The 1770 famine was the first of many policy-induced catastrophes that would kill tens of millions over the next 177 years.

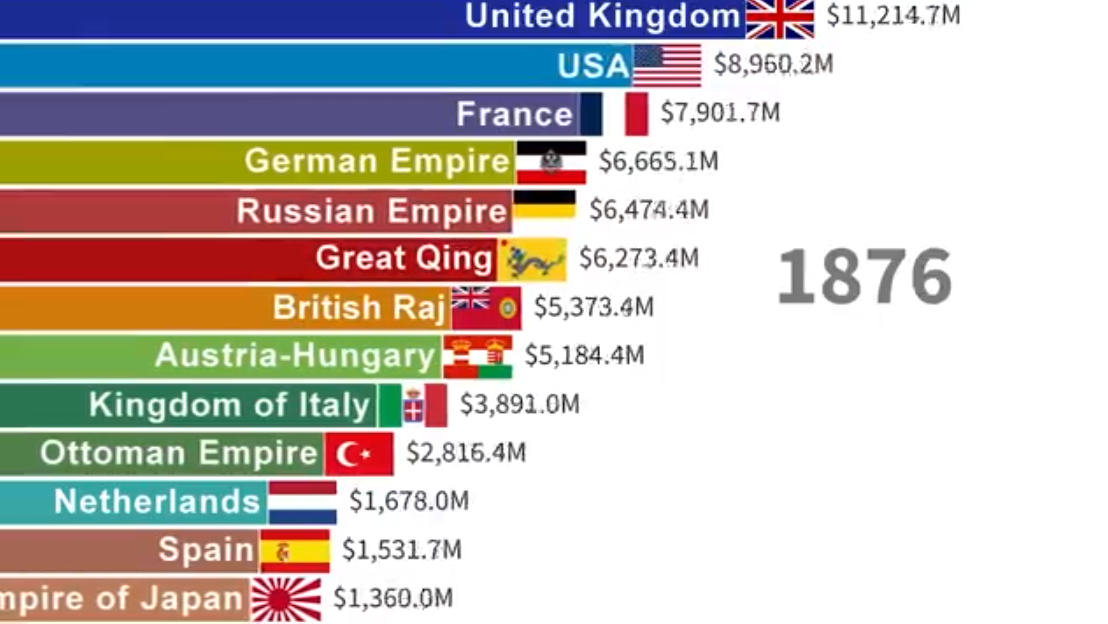

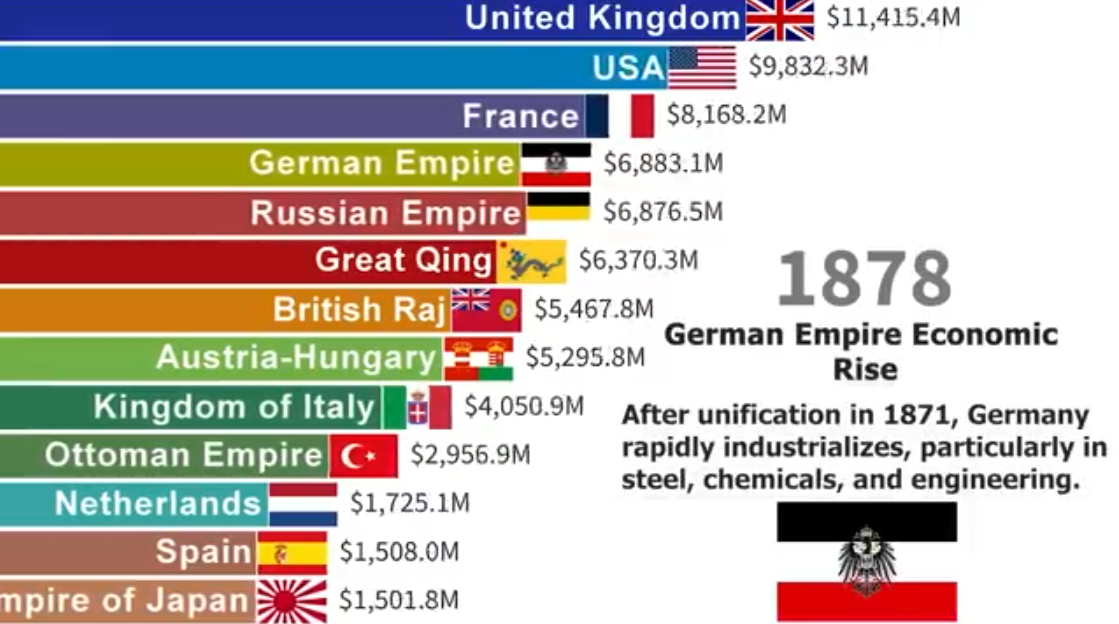

The Late Victorian Holocausts: 1876-1902

In the second half of the 19th century, large-scale excess mortality was caused by: the Great Famine of 1876–1878 (5.5 million deaths), the Indian famine of 1896–1897 (5 million deaths), and the Indian famine of 1899–1900 (1 million deaths). These famines, occurring during Queen Victoria’s reign, killed more Indians than all British wars combined.

The Great Famine of 1876-1878: “Extermination Camps”

The Great Famine of 1876-1878 affected millions, with fatalities estimated in a range from 5.6 million to 9.6 million, with a careful modern demographic estimate of 8.2 million deaths. This famine occurred primarily in southern India, affecting Madras Presidency, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Bombay Presidency.

The famine occurred during a severe drought caused by El Niño. But the drought didn’t cause the famine—British policies did.

Lytton’s Criminal Policies

Lord Lytton served as Viceroy during the 1876-1878 famine. His policies revealed the utter contempt British officials had for Indian lives:

Laissez-faire and the “Temple wage”: Famine Commissioner Sir Richard Temple narrowed relief eligibility and cut rations in January 1877 to a so-called “Temple wage”: ~1 lb of grain and one anna for a full day’s heavy labour, explicitly warning that relief must not become “excessive.” Dr. W. R. Cornish, Sanitary Commissioner, protested that at least 1.5 lb with protein was physiologically necessary, but Viceroy Lytton backed Temple, who argued “everything must be subordinated to the financial consideration of disbursing the smallest sum of money.” (Government response summary; Great Famine overview) The outcome was predictable: meagre relief, strict work tests, and high mortality across relief works. Modern demographic work places excess deaths for 1876–78 at ~5.6–9.6 million (best estimate ~8.2 million). (Great Famine).

Continued Exports: While millions starved in southern India, grain exports to Britain actually increased. Records show that between 1875-1878, India exported 6.4 million hundredweight of wheat to Britain. The British prioritized feeding their own population over feeding starving Indians.

The Delhi Durbar: While millions starved in southern India, Lord Lytton organized the Delhi Durbar in January 1877—an elaborate celebration proclaiming Queen Victoria as Empress of India. The week-long festivities cost £100,000 and included lavish feasts for 68,000 guests while simultaneously, just a few hundred miles away, millions of Indians were dying of starvation.

The Ideological Justification

British officials justified their policies with racist ideology:

Malthusian Theory: They claimed famines were natural population control, necessary to prevent overpopulation. Indians dying was portrayed as inevitable, even beneficial.

Racial Superiority: British officials openly expressed beliefs that Indians were naturally improvident and lazy, responsible for their own starvation.

Free Market Fundamentalism: Interference with grain markets was portrayed as economically unsound, even as millions died.

The Pattern Repeats: 1896-1897 and 1899-1900

The Indian famine of 1896–1897 killed 5 million people, while the Indian famine of 1899–1900 killed 1 million. These famines followed the same pattern:

Drought Triggers, Policy Causes: Natural drought created crop failures, but British policies—inflexible revenue demands, grain exports, inadequate relief—turned drought into famine.

Inadequate Relief: Relief efforts were deliberately inadequate. The British feared that adequate relief would make Indians “dependent” on government assistance.

Export Priority: Even during famine conditions, India remained a net exporter of grain. The British prioritized export earnings over feeding Indians.

Racial Contempt: British officials consistently blamed Indian “laziness” and “overpopulation” for famines caused by British policies.

The Bengal Famine of 1943: Churchill’s Genocide

The Bengal Famine of 1943 killed an estimated 3 million people, making it one of the deadliest famines of the 20th century. Unlike the 19th-century famines, the 1943 famine occurred during World War II, revealing that even in the 20th century, British priorities placed Indian lives at the bottom.

The Causes: British Wartime Policies

The 1943 famine was not caused by drought or natural disaster. It was entirely man-made, resulting from deliberate British policies:

Denial Policy: Fearing Japanese invasion of Bengal, the British implemented a “denial policy”—destroying boats used for fishing and transportation, and removing rice stocks from coastal areas. This destroyed Bengal’s economy and created artificial scarcity.

Military Priority: The British diverted Bengal’s food resources to feed Allied troops. Indian food security was sacrificed for military needs.

Hoarding and Speculation: British policies encouraged hoarding and speculation, driving up food prices beyond what ordinary Bengalis could afford.

Trade Restrictions: The British prevented grain from moving into Bengal from other Indian regions, even as famine conditions developed.

Export Continuation: Even during the famine, India continued exporting food to other parts of the British Empire, including Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

Churchill’s Criminal Negligence and Racism

Winston Churchill, revered in Britain as a wartime hero, was directly responsible for the Bengal Famine through his policies and his racist contempt for Indians:

Refusal to Provide Relief: When told of the famine, Churchill initially refused to provide relief grain, claiming shipping was needed for the war effort. Yet British records show sufficient shipping was available—it was simply not prioritized for Indian relief.

War cabinet priorities and private remarks: Contemporary records and ministerial diaries show London knew Bengal was collapsing but prioritised war logistics. Leo Amery (Secretary of State for India) recorded Winston Churchill’s remarks about Indians as “a beastly people with a beastly religion” and complaints that relief would only encourage those who “breed like rabbits.” (see BBC overview of the famine and ministerial exchanges: BBC: “Why Churchill’s legacy is being questioned in India”). Whether or not every quoted quip shaped Cabinet orders, the documentary trail is clear on delayed shipping of grain, “denial” measures that disrupted local rice/fishing economies, and price spikes that pushed food out of reach for the poor. (Bengal famine 1943—detail & sources)

Indian voices on the ground: Bengali artist-reporter Chittaprosad documented the catastrophe in Hungry Bengal (1943)—a tour through Midnapore with sketches, names, and testimonies the authorities tried to suppress. A later facsimile of this field report is available here (PDF). These indigenous records—alongside newspaper photo-spreads in The Statesman—made the bodies on Calcutta’s streets impossible to deny.

“Beastly People with Beastly Religion”: According to Leo Amery’s diary, Churchill called Indians “a beastly people with a beastly religion” and claimed “the famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits”.

Amery’s Assessment: Leo Amery, Secretary of State for India, privately decided that “on the subject of India, Winston is not quite sane,” and recorded in August 1944 Churchill’s remark that relief would do no good because Indians “breed like rabbits” and will outstrip any available food supply.

The Death Toll and Its Impact

The Bengal Famine of 1943 killed approximately 3 million people. The deaths occurred through starvation, disease (as weakened bodies succumbed to cholera, malaria, and smallpox), and complete breakdown of social order.

Contemporary accounts describe horrific scenes:

- Families abandoning elderly members and children they couldn’t feed

- People dying in the streets of Calcutta while British soldiers and officials lived in comfort

- Desperate mothers trying to sell their children for food

- Bodies piling up faster than they could be cremated or buried

The psychological trauma of the famine scarred Bengal for generations. Survivors lived with memories of watching family members slowly starve to death while British authorities refused to provide adequate relief.

The Famine Commission: Whitewash and Deflection

After the famine, the British appointed a Famine Commission to investigate. The Commission’s report, while acknowledging the massive death toll, largely absolved the British administration of responsibility. It blamed:

- Natural causes (despite no drought or major crop failure)

- “Hoarding” by Indian merchants (ignoring British policies that encouraged speculation)

- Population pressure (the Malthusian excuse)

- “Panic buying” (ignoring artificial scarcity created by British policies)

The Commission’s report was a whitewash, designed to protect British officials from accountability for mass death caused by their policies.

What official inquiries conceded: The Famine Commission (1880) acknowledged that earlier relief practice was inadequate and codified Famine Codes precisely because mortality had been catastrophic. The Commission debated minimum subsistence rations (Temple vs. Cornish) and the conditions for public works, leaving a paper trail on the political economy of parsimony. (See Report of the Indian Famine Commission, 1880; short overview UNU-WIDER working paper.)

The Pattern Across Famines: British Policy as Genocide

Examining the major famines reveals consistent patterns that demonstrate British culpability:

1. Inflexible Revenue Demands

In every famine, British authorities continued demanding revenue payments regardless of crop failures or economic conditions. Peasants were forced to sell seed grain, implements, and possessions to pay taxes even as they starved.

Traditional Indian rulers had always remitted or reduced taxes during famines. The British never did. Revenue extraction took absolute priority over human life.

2. Export Priority Over Food Security

During every major famine, India continued exporting food. The British prioritized export earnings and feeding their own population over feeding starving Indians. This reveals the fundamental nature of colonial rule—India existed to enrich Britain, and Indian deaths were acceptable costs.

3. Inadequate or Absent Relief

The British either provided no relief (as in 1770) or deliberately made relief so inadequate and harsh that many chose starvation over accepting it (as in 1876-1878). Relief camps became death traps with mortality rates exceeding 90%.

Traditional Indian rulers had maintained granaries, organized public works during famines, and seen famine relief as a sovereign’s duty. The British saw it as economically unsound interference with markets.

4. Racist Ideological Justification

British officials consistently blamed Indians for their own starvation:

- Indians were “lazy” and “improvident”

- Indians were “breeding like rabbits,” causing overpopulation

- Famines were natural population control (Malthusian ideology)

- Indian culture made them naturally vulnerable to famine

This racist ideology served to absolve British officials of responsibility for deaths caused by their policies.

5. Continuation of Exploitation During Crisis

The British never suspended their economic exploitation during famines. They continued extracting revenue, maintaining exports, and prioritizing British economic interests over Indian survival. The famines reveal the fundamental principle of colonial rule: Indians were resources to be extracted, not subjects to be protected.

Contrasting Pre-Colonial and Colonial Famine Management

The devastating famines under British rule stand in stark contrast to how pre-colonial Indian rulers managed food crises:

Pre-Colonial Famine Management

Traditional Indian rulers, whether Hindu or Muslim, had established systems for managing droughts and crop failures:

State Granaries: Rulers maintained granaries that stored grain during good years for distribution during bad years.

Tax Remission: During famines, rulers remitted or postponed tax collection, allowing peasants to keep food and seed grain.

Public Works: Rulers organized public works projects during famines, providing employment and income so people could buy food.

Market Regulation: Rulers prevented hoarding and speculation, ensuring grain reached those who needed it.

Direct Relief: In severe cases, rulers distributed food directly to the affected population.

These measures didn’t prevent all famine deaths—severe droughts would always cause hardship. But they prevented droughts from becoming catastrophic famines killing millions.

British Colonial Famine Management

The British systematically destroyed traditional famine management systems:

No Granaries: The Company and later the Crown maintained no grain reserves for famine relief.

Inflexible Revenue: Tax demands continued regardless of crop conditions or economic hardship.

No Public Works: Public works were provided grudgingly, if at all, and deliberately made harsh to discourage participation.

Free Market Ideology: The British refused to regulate grain markets, allowing hoarding and speculation to drive up prices during shortages.

Minimal Relief: Relief, when provided, was deliberately inadequate—based on the ideological principle that Indians shouldn’t become “dependent” on government assistance.

The contrast reveals a fundamental difference: traditional Indian rulers saw protecting subjects from famine as a sovereign duty. The British saw famine relief as economically unsound interference with markets and potentially making Indians “lazy.”

The Total Death Toll: Quantifying the Genocide

During the era of British rule in India (1765–1947), 12 major famines occurred which led to the deaths of millions of people. The major famines and their death tolls include:

- 1769-1770: Great Bengal Famine – 10 million deaths

- 1783-1784: Chalisa famine – 10-11 million deaths

- 1791-1792: Doji bara famine (Skull famine) – 11 million deaths

- 1837-1838: Agra famine – 800,000 deaths

- 1860-1861: Upper Doab famine – 2 million deaths

- 1865-1867: Orissa famine – 1 million deaths

- 1868-1870: Rajputana famine – 1.5 million deaths

- 1873-1874: Bihar famine – unknown deaths

- 1876-1878: Great Famine – 5.5-8.2 million deaths

- 1896-1897: Indian famine – 5 million deaths

- 1899-1900: Indian famine – 3–4.4million deaths

- 1943-1944: Bengal Famine – 3 million deaths

Conservative estimates suggest these famines killed 30-40 million Indians. Some historians have established that tens of millions of Indians died of starvation during several considerable policy-induced famines in the late 19th century, as their resources were siphoned off to Britain and its settler colonies. Some estimates suggest the total could be as high as 60 million deaths over the entire colonial period.

To put this in perspective:

- The Holocaust killed approximately 6 million Jews

- The Irish Potato Famine killed approximately 1 million Irish

- The Soviet famines under Stalin killed approximately 6-8 million

- The Chinese Great Famine killed approximately 15-55 million

British-made famines in India killed 30-60 million people over 182 years of colonial rule. This represents one of the greatest death tolls from any policy-induced disaster in human history.

Visit the Links to See Evidence

| Famine / Year | Estimated Deaths | Supporting Source / Link |

|---|---|---|

| 1769–1770 Great Bengal Famine |

~10 million | Wikipedia – Great Bengal Famine of 1770 |

| 1783–1784 Chalisa Famine |

~11 million | Wikipedia – Chalisa Famine |

| 1791–1792 Doji Bara (“Skull”) Famine |

~11 million | Wikipedia – Doji Bara Famine |

| 1837–1838 Agra Famine |

~800,000 | Wikipedia – Agra Famine |

| 1860–1861 Upper Doab Famine |

~2 million | Wikipedia – Upper Doab Famine |

| 1865–1867 Orissa Famine |

~1 million | Wikipedia – Orissa Famine |

| 1868–1870 Rajputana Famine |

~1.5 million | Wikipedia – Rajputana Famine |

| 1873–1874 Bihar Famine |

Unknown (millions at risk) | Wikipedia – Bihar Famine |

| 1876–1878 Great Famine (Madras / Deccan) |

5.6–9.6 million | Wikipedia – Great Famine of 1876–78 Smithsonian – British Policies & Indian Famine |

| 1896–1897 Indian Famine |

~5 million | Wikipedia – Indian Famine 1896–1897 |

| 1899–1900 Indian Famine |

~1–4.5 million | Academia.edu The demography of Indian |

| 1943–1944 Bengal Famine |

1.5–3.8 million | Wikipedia – Bengal Famine of 1943 BBC – Churchill’s Role in Bengal Famine |

Why Britain Never Apologized

Despite this staggering death toll—tens of millions killed by deliberate policy over nearly two centuries—Britain has never apologized for colonial famines. The reasons reveal continuing colonial mentalities:

Denial of Responsibility

British historians and apologists consistently deny that British policies caused the famines. They claim:

- Famines were caused by natural disasters (droughts)

- Indian overpopulation made famines inevitable

- British relief efforts saved lives rather than causing deaths

- Free market policies were economically sound

- Indians were responsible for their own starvation

This denial ignores massive historical evidence that British policies—inflexible revenue demands, continued exports, inadequate relief, destruction of traditional famine management systems—directly caused famine deaths.

Colonial Nostalgia

In Britain, colonial rule is still widely viewed with nostalgia rather than shame. British education minimizes colonial atrocities while emphasizing supposed British contributions (railways, telegraph, rule of law). The famines, when mentioned at all, are portrayed as unfortunate natural disasters rather than policy-induced genocides.

Economic Interests

Acknowledging British responsibility for colonial famines would create pressure for reparations. If Britain admitted that its policies killed 30-60 million Indians, demands for compensation would be unavoidable. Britain has consistently refused even to consider reparations for colonial exploitation.

Legal Protection

Britain has crafted laws that make colonial-era crimes effectively unchallengeable. Statutes of limitations, sovereign immunity, and legal definitions of genocide all serve to protect Britain from accountability for historical atrocities.

Continuing Racism

Underlying British denial is continuing racism—the belief that Indian lives matter less than British lives, that British economic interests justified Indian deaths, and that Indians were somehow responsible for their own starvation despite overwhelming evidence of British culpability.

The Post-Independence Record: No Famines

One of the most telling pieces of evidence that British policies caused famines is the post-independence record: since 1947, independent India has experienced severe droughts but no major famines. This demonstrates that famines under British rule were not inevitable results of climate or overpopulation—they were results of colonial policies.

Why Independent India Avoided Famines

Democratic Accountability: Elected governments face political consequences for allowing famines, creating incentives to prevent them that colonial administrators never faced.

Food Security Policies: India built grain reserves, established public distribution systems, and prioritized food security in ways the British never did.

Market Regulation: India regulates grain markets during shortages, preventing the hoarding and speculation that the British allowed.

Relief Systems: India has established disaster relief systems that provide assistance during droughts, preventing them from becoming famines.

Economic Priorities: Independent India prioritizes feeding its population over export earnings—the opposite of British priorities.

The contrast is stark: British rule (1765-1947) saw 12 major famines killing 30-60 million people. Independent India (1947-present) has seen zero major famines despite experiencing severe droughts. This proves that famines under British rule were policy-induced, not inevitable.

Why Believe the Contents — and What Scholars Debate

This article draws upon extensive colonial-era documentation, famine commission reports, and modern demographic reconstructions that show how British administrators fully understood the human cost of their revenue and export priorities. Contemporary writings—from William Bolts’ Considerations on India Affairs (1772) to W. W. Hunter’s Annals of Rural Bengal (1868)—confirm that officials were informed of mass starvation yet prioritized fiscal returns.

At the same time, academic historians continue to debate the relative weights of various causes.

Tirthankar Roy in Famines in India: Enduring Lessons and Cormac Ó Gráda in Re-examining the Bengal Famine of 1943 emphasize that climate variation, monsoon failure, crop disease, and market breakdowns also contributed to famine conditions.

Demographers Dyson & Ó Gráda (Famine Demography Overview) quantify how mortality correlated with administrative delay and relief parsimony rather than pure natural scarcity.

Yet across this scholarship, one conclusion endures: colonial fiscal rigidity, laissez-faire ideology, and export obsession transformed environmental stress into systemic mass death.

Even historians who foreground climate or disease acknowledge that the British refusal to suspend taxation, regulate grain markets, or release stocks amplified natural dearth into genocide-scale catastrophe.

The Greatest Crime Britain Won’t Acknowledge

British-made famines in India killed 30-60 million people over 182 years—more than the Holocaust, more than Stalin’s purges, rivaling even Mao’s Great Famine. These deaths were not accidental. They were the direct, foreseeable result of British policies that prioritized revenue extraction and export profits over Indian lives.

Colonial administrators were fully aware of the consequences of their policies. They received reports of mass starvation. They saw bodies piling up in streets. They heard pleas for relief. And they chose to continue extracting revenue, maintaining exports, and providing inadequate relief because British economic interests always took priority over Indian lives.

The Great Bengal Famine of 1770—killing 10 million just five years after the Company gained revenue rights—set the pattern. The 1876-1878 famine—where relief centers approached 94% mortality rates and the Viceroy outlawed private charity—revealed the systematic cruelty of British policies. The Bengal Famine of 1943—where Churchill made racist comments about Indians “breeding like rabbits” while 3 million died—showed that colonial contempt for Indian lives persisted to the very end.

These were not natural disasters. They were not inevitable results of overpopulation or climate. They were genocides—systematic, policy-induced mass deaths that British authorities could have prevented but chose not to because doing so would have reduced British profits.

Britain has never apologized for these deaths. British education minimizes them. British historians deny British responsibility. British law protects Britain from accountability. But the evidence is overwhelming: British policies killed tens of millions of Indians through deliberate, systematic policies that prioritized British economic interests over Indian survival.

The famines reveal the fundamental nature of colonialism: Indians were not subjects to be governed but resources to be extracted. When extraction conflicted with survival, the British always chose extraction. Tens of millions of deaths were the price Indians paid for enriching Britain.

Yet even systematic economic drain, physical looting of treasures, and genocidal famines don’t complete the picture of colonial devastation. The British also used India’s resources—material and human—to fund their own Industrial Revolution while systematically deindustrializing India. This final dimension of exploitation—how British prosperity was built on Indian impoverishment—is the subject of our final blog.

🔹Call to Action

The British-made famines in India killed 30-60 million people—one of the greatest death tolls from policy-induced disaster in human history. Yet Britain has never apologized, never acknowledged responsibility, and never paid reparations. Understanding this genocide is crucial to demanding historical justice.

Support our effort to document colonial crimes by sharing this series and contributing to this project.

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Watch the Videos

Glossary of Terms

- Chalisa Famine: A famine in Vikram Samvat 1840 in North India is named “Chalisa Famine” owing to the Hindu Calendar year.

-

Diwani Rights: Revenue-collection rights granted to the East India Company in 1765 by the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II after the Treaty of Allahabad.

-

Dual System: A governance arrangement (1765–1772) in Bengal where the Nawab retained nominal authority while the East India Company controlled revenues—causing administrative chaos and famine.

-

Temple Wage: A ration scale fixed by British officials during the 1876–78 famine, allowing barely one pound of grain per day for laborers, often leading to death by starvation.

-

Malthusian Theory: A 19th-century British demographic idea asserting that population growth naturally outpaces food supply, used to justify famines as “natural checks.”

-

Denial Policy: A 1942–43 British military policy in Bengal destroying boats, rice stocks, and transport to prevent Japanese use—triggering famine conditions.

-

Famine Codes: Official colonial guidelines (post-1880) defining relief criteria, rations, and labor tests; designed more for fiscal control than humanitarian relief.

-

Dadabhai Naoroji’s Drain Theory: The 19th-century Indian nationalist’s economic theory demonstrating systematic wealth transfer from India to Britain.

-

Home Charges: Annual payments extracted from Indian revenues to fund Britain’s administrative, military, and debt costs—one of the key mechanisms of economic drain.

-

Laissez-faire: The British economic doctrine of minimal government interference in markets, invoked to block relief and justify non-intervention during famines.

-

Leo Amery Diaries: Wartime notes by Britain’s Secretary of State for India revealing Churchill’s racist remarks and policy indifference during the Bengal Famine.

-

Warren Hastings: First Governor-General of India (1773–1785), who abolished the Dual System but maintained exploitative revenue collection policies.

-

Richard Temple: British administrator and Famine Commissioner who codified “Temple wages” during the Great Famine of 1876–78.

-

William Wilson Hunter: British civil servant and historian whose Annals of Rural Bengal (1868) documented the horrors of the 1770 famine.

-

William Bolts: Former East India Company official turned whistleblower; author of Considerations on India Affairs (1772), a major exposé of Company exploitation.

-

Chittaprosad’s Hungry Bengal: A 1943 illustrated eyewitness report documenting the Bengal Famine’s human suffering, censored by the British Raj.

#BengalFamine #BritishGenocide #ColonialIndia #FamineHistory #HinduinfoPedia

Follow us:

- English YouTube: Hinduostation – YouTube

- Hindi YouTube: Hinduinfopedia – YouTube

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

Previous Blogs of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-from-traders-to-rulers/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-treaty-of-allahabad-1765/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-vs-maratha-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/divide-and-rule-by-east-india-company/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/economy-in-british-raj-the-systematic-drain-of-indian-wealth/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-stole-indian-treasures-colonial-plunder-and-cultural-genocide/

Other related blogs and posts

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-rule-in-india-a-blessing-or-a-curse/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-education-system-and-its-legacy/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/islamic-influence-and-jazia-tax-in-india/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/battle-of-plassey-a-pivotal-turning-point-in-indian-history/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-arjan-dev-ji-architect-of-faith-and-martyrdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/maratha-empire-decline-consequences-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-har-rai-a-legacy-of-compassion-and-strength/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-independence-and-mutiny-in-india-1857/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indias-freedom-struggle-efforts-and-quit-india-movement-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-tyrannical-monuments-a-legacy-of-despotism/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-ascent-governance-and-policy-dynamics/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-early-life-prelude-to-power-of-criminal-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/ahmad-shah-abdali-and-the-vadda-ghalughara-massacre/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/guru-tegh-bahadur-legacy-of-faith-and-freedom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-legacy-unraveling-controversies-of-mysore-tiger/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-a-true-muslim/

- https://hinduinfopedia.com/gurukul-truths-of-hindu-wisdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/gurukul-education-system-a-journey-through-time/

Leave a Reply