British Loot and Industrialize: How India Funded Britain’s Rise

Part VIII: Study of East India Company and Foreign rule in Bharat

British Loot and Industrialize: How India Funded Britain’s Rise

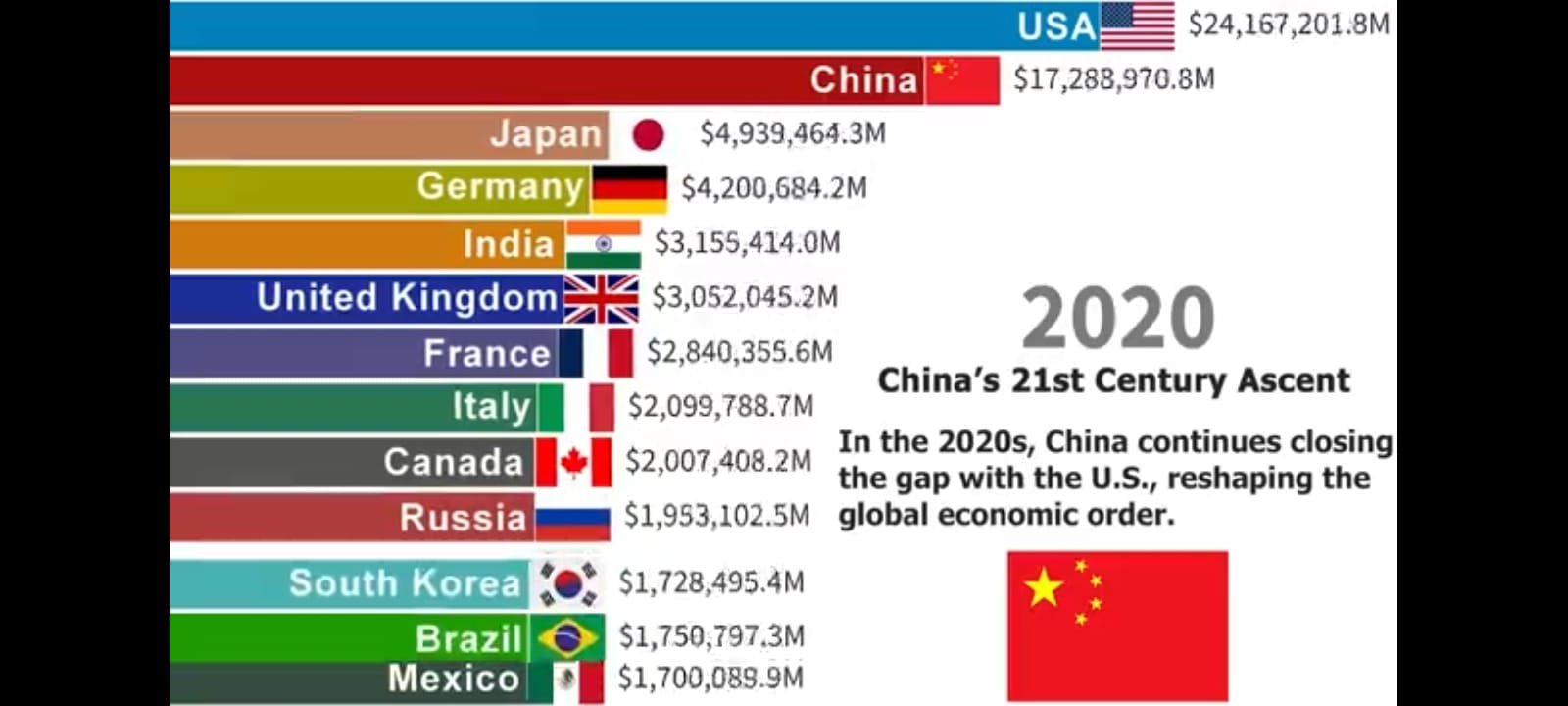

The rise of Britain as the first industrial power is often celebrated as the triumph of innovation and enterprise. Yet behind the glowing narratives of steam engines, textile mills, and global trade lay a darker truth — the empire’s industrial ascent was financed by British loot from India. What Europe called “progress” was, in large part, the systematic economic drain of a prosperous civilization that once accounted for nearly a quarter of the world’s GDP.

This blog continues the Study of East India Company and Foreign Rule in Bharat series, following the earlier chapters that exposed the Doctrine of Lapse, the Drain of Wealth, and the policy-induced famines that wiped out millions. Having seen how the Company’s conquests and famine policies devastated India’s social fabric, we now turn to the next stage — how that extracted wealth was reinvested to industrialize Britain and transform it from a minor maritime kingdom into the world’s manufacturing hub.

Between 1765 and 1938, the British Empire extracted an estimated $45 trillion (in 2018 value) from India through trade underpayments, taxation, and “Home Charges.” This transfer — the largest in human history — provided the capital, raw materials, and captive markets that powered Britain’s Industrial Revolution. India’s decline mirrored Britain’s rise: the looms of Dhaka fell silent while those of Manchester roared; Bengal’s surplus financed London’s banks; and India’s artisans were taxed into extinction to subsidize English industry.

This blog examines how the East India Company’s economic model evolved into the imperial machinery that drained India’s wealth, how British policies turned India into both supplier and consumer of British goods, and how the destruction of India’s self-sufficient economy fueled the Industrial Revolution.

Understanding British loot and industrialization is crucial not merely to revisit past injustice, but to recognize that the so-called “modernity” of the West was built upon the impoverishment of the East. Britain’s industrial glory did not emerge from invention alone — it was financed by India’s exploitation.

The Timing: British Industrialization and Indian Extraction

The chronological correlation between British acquisition of Bengal revenues and British industrialization is striking and revealing:

- 1765: Treaty of Allahabad grants Company Diwani rights over Bengal, providing £3 million annually in revenues

- 1769: James Watt patents the steam engine—the technology that would power the Industrial Revolution

- 1770: Great Bengal Famine kills 10 million Indians; Company revenues temporarily disrupted but quickly restored at higher levels

- 1780s-1790s: British textile industry begins mechanization; Manchester emerges as textile manufacturing center

- 1800s: British Industrial Revolution accelerates; India’s share of global manufacturing begins catastrophic decline

- 1850s: Railways built in India—not for Indian development but to extract raw materials and distribute British manufactures

This timeline reveals a pattern: as wealth extraction from India intensified, British industrialization accelerated. The two processes were directly linked—Indian wealth provided the capital that financed British industrial transformation.

Bengal Revenues: The Foundation of British Capital

When the East India Company gained Diwani rights in 1765, Bengal became the richest prize in the British Empire. Bengal alone generated approximately £3 million annually—equivalent to perhaps £3 billion in today’s money. This represented an enormous influx of wealth that fundamentally transformed British economic possibilities.

How Bengal Revenues Funded British Expansion

- Military Campaigns: Bengal revenues funded the Company’s military expansion throughout India. Each new conquest was financed by revenues from previous conquests, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of expansion funded by Indian wealth.

- Company Dividends: Massive dividends paid to Company shareholders—wealthy British citizens—provided them with capital to invest in British industries. The fortunes made by Company officials and shareholders became seed capital for industrial ventures.

- Infrastructure Investment: While the Company invested minimal amounts in Indian development, they invested heavily in British infrastructure, shipping, and commerce—all funded by Indian revenues.

- Trade Capital: Bengal revenues provided the capital to finance British trade globally. British merchants could now compete with Dutch, French, and Portuguese competitors because they had access to Indian wealth.

The “Nabobs”: Fortunes Made in India, Invested in Britain

Company officials made enormous personal fortunes in India through corruption, private trade, and exploitation. These “nabobs” (from “nawab”) returned to Britain with wealth that they invested in:

Industrial Ventures: Factories, mills, and manufacturing enterprises Real Estate: Country estates, urban properties, agricultural land Parliamentary Seats: Buying influence in British politics Banking and Finance: Establishing financial institutions

Robert Clive, architect of British conquest in Bengal, returned to Britain with a fortune estimated at £500,000 (equivalent to hundreds of millions today). He used this wealth to buy parliamentary seats and estates. Multiplied across hundreds of Company officials, the wealth extracted from India and invested in Britain represented a massive capital transfer that funded British economic development.

Deindustrializing India, Industrializing Britain

Perhaps the most devastating aspect of British colonialism was the systematic deindustrialization of India combined with industrialization of Britain using Indian resources. The period from 1780 to 1860 saw a dynamic shift in India’s economy from a world leading processed goods exporter to the extraction and export of raw materials to Britain and buyer of manufactured goods from Britain.

India’s Pre-Colonial Industrial Strength

Before British rule, India was one of the world’s leading manufacturing economies:

- Textiles: India produced 25% of global textile output. Indian cotton cloth, silk, and muslin were prized worldwide for their quality and craftsmanship.

- Shipbuilding: Indian-built ships were superior to European vessels. British ships were often built in Indian shipyards.

- Steel: Indian steel, particularly wootz steel from South India, was famous for its quality. Damascus swords were made from Indian steel.

- Crafts: Indian artisans produced jewelry, weapons, decorative items, and luxury goods that dominated global markets.

This industrial strength made India wealthy and created employment for millions of artisans, weavers, metalworkers, and craftspeople.

The Systematic Destruction

The British systematically destroyed Indian industries through deliberate policies:

Phase 1: Control Production (1760s-1810s)

After gaining control of Bengal, the Company forced Indian producers to sell exclusively to them at artificially low prices. Weavers who refused had their thumbs cut off—literally destroying their ability to practice their craft. Traditional merchant networks were dismantled. Indian producers were reduced to virtual slaves producing for Company profit.

Phase 2: Tariff Manipulation (1810s-1850s)

The British imposed massive tariffs on Indian textiles entering Britain (70-80%) while British textiles entered India duty-free or with minimal tariffs. This made competition impossible. Indian textiles that had dominated British markets were priced out. Meanwhile, British manufactured textiles flooded Indian markets, undercutting local producers.

The impact was catastrophic. In 1813, India still exported textiles competitively. By 1850, India’s textile industry was decimated. The weavers of Dacca, who had produced the world’s finest muslin, were reduced to poverty or forced into agricultural labor.

Phase 3: Railway-Enabled Market Destruction (1850s-1900s)

Railways—often cited as British “development” of India—primarily served to:

- Transport raw cotton from Indian farms to ports for export to British mills

- Distribute British-manufactured textiles throughout India’s interior

- Destroy local industries that had been protected by transportation costs

The Statistics of Industrial Destruction

The numbers tell the story of systematic industrial destruction:

- 1750: India produced 25% of world’s textiles, Britain less than 2%

- 1900: Britain produced 25% of world’s textiles, India less than 2%

- 1750: India’s manufacturing output was 25% of global total

- 1900: India’s manufacturing output was less than 2% of global total

- Employment: Millions of Indian weavers, artisans, and craftspeople lost their livelihoods

This reversal—from India as manufacturing powerhouse to Britain as “workshop of the world”—was not natural economic evolution. It was deliberate policy implemented to benefit British industry at Indian expense.

The Cotton Triangle: Extracting Raw Materials, Destroying Processors

The transformation of India’s cotton industry perfectly illustrates British economic exploitation:

Agriculture: The Silent Engine of Extraction

Beyond cotton, British colonial policy reshaped India’s entire agricultural landscape into a system of forced specialization. Regions once cultivating diverse food crops were pushed toward export-oriented cash crops such as indigo, jute, tea, and opium. This deliberate shift served imperial factories, not Indian plates.

Peasants were compelled to grow indigo and opium under coercive contracts, often at the cost of subsistence farming. The Permanent Settlement in Bengal and ryotwari systems elsewhere turned cultivators into revenue-bound tenants with no relief during droughts. Land that once sustained villages became a raw-material pipeline for British mills.

The result was a structural famine trap — declining soil fertility, rising debt, and vulnerability to price shocks. Agriculture under colonialism ceased to be a source of local prosperity and became an instrument of industrial feedstock for Britain.

Before British Rule

India grew cotton, processed it into yarn and cloth, and exported finished textiles worldwide. The entire value chain—from agriculture to manufacturing to export—was located in India, providing employment and wealth to Indian farmers, spinners, weavers, and merchants.

Under British Rule

The British transformed this integrated industry into extractive colonialism:

Step 1: Indian farmers forced to grow cotton for export to Britain rather than for domestic processing. Prices paid to farmers were artificially low, set by British commercial monopolies.

Step 2: Raw cotton exported to British mills in Manchester and Lancashire. Indian processing destroyed through tariffs and forced de-skilling (cutting weavers’ thumbs).

Step 3: British mills processed Indian cotton into cloth using mechanized production. British workers employed; British capitalists enriched.

Step 4: British-manufactured cloth exported back to India and sold at prices that undercut remaining Indian handloom weavers.

The result: India lost manufacturing employment and wealth. Britain gained manufacturing employment and wealth. The same raw material—Indian cotton—now enriched Britain instead of India.

The Employment Catastrophe

Deindustrialization meant millions of Indians lost their traditional livelihoods:

- Weavers: From millions employed in textile production to nearly complete unemployment by 1900

- Spinners: Mechanized British mills eliminated the need for hand spinning that had employed millions of Indian women

- Artisans: Craftspeople producing traditional goods lost markets as British mass production undercut their products

- Merchants: Traditional merchant networks collapsed as British trading companies monopolized commerce

These millions of unemployed industrial workers were forced into agriculture, fragmenting landholdings into uneconomic units and increasing rural poverty. India transformed from a balanced economy with substantial manufacturing employment into an overwhelmingly agricultural economy unable to support its population.

The Railway Myth: Infrastructure for Extraction

British apologists often cite railways as evidence that colonial rule benefited India. The reality was that Indian railways were infrastructure for exploitation, not development.

Who Paid, Who Benefited?

Indians Paid Everything:

- British railway companies were guaranteed 5% return on investment—paid from Indian revenues even when railways lost money

- All construction costs came from Indian taxation—approximately £350 million by 1914

- Land acquisition costs paid by Indian revenues

- Operating losses covered by Indian taxpayers

British Benefited:

- Guaranteed returns for British investors—risk-free profit funded by Indian taxes

- British companies supplied rails, engines, and equipment

- British engineers received inflated salaries

- British commercial interests gained transportation for raw materials and finished goods

The Real Purpose of Indian Railways

Railways were not built to develop India but to serve British economic and military interests:

Economic Purpose:

- Transport raw materials (cotton, jute, tea, grain) from interior to ports for export

- Distribute British manufactured goods throughout India

- Destroy local industries by breaking their transportation-cost protection

- Generate guaranteed profits for British investors

Military Purpose:

- Rapidly move British troops to suppress resistance

- Control India’s interior from coastal bases

- Facilitate military campaigns in Afghanistan and Burma

Contrasting Colonial and Post-Colonial Railways

The colonial railway system’s extractive purpose becomes clear when compared to post-independence development:

Colonial Railways (1853-1947):

- Connected raw material sources to ports, not Indian cities to each other

- Used wide gauge incompatible with neighboring regions to prevent Indian industrial integration

- Minimal investment in passenger service; priority was freight extraction

- Profits guaranteed to British companies; losses covered by Indian taxes

Post-Independence Railways:

- Integrated national network connecting Indian cities and regions

- Focus on passenger service and national connectivity

- Owned and operated by Indian government

- Revenues support Indian development

The contrast reveals that railways could serve development—but under British rule, they served extraction.

The Opium Trade: Forced Cultivation for Imperial Profit

Mining, Tea, and Oil: The Broader Web of Extraction

The opium fields of Bengal were only one strand in the web of British extraction. India’s mineral and plantation sectors were reorganized to supply Britain’s industrial expansion.

Tea Plantations: The hills of Assam and Darjeeling were converted into vast tea estates owned by British companies and worked by indentured Indian laborers under near-slave conditions. Profits flowed to London tea firms, while Indian workers lived and died in debt bondage.

Coal and Iron Ore: India’s mines in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa were opened for British companies, powering British locomotives and steamships. Wages were meagre, safety nonexistent, and export priority absolute.

Petroleum: The discovery of oil in Assam in the late 19th century quickly became another resource under British corporate control. Indian refineries were suppressed so that crude could be shipped and processed abroad.

These industries reveal how deeply India’s natural wealth was integrated into Britain’s industrial machine — every field, mine, and plantation aligned to the needs of imperial production.

One of the most morally bankrupt aspects of British economic policy was the opium trade, which revealed the complete subordination of Indian welfare to British profit.

The Triangular Trade System

The Chinese needed payment in silver for their tea, which drained British silver reserves. To address this imbalance, the British East India Company started growing and processing opium in Bengal, India, to smuggle it into China illegally.

The British established a triangular trade system:

India to China: British forced Indian peasants to grow opium, which was smuggled into China despite Chinese laws against opium imports. The British used the profits from the sale of opium to purchase such Chinese luxury goods as porcelain, silk, and tea, which were in great demand in the West, while addiction to opium became widespread in China, leading to social and economic problems there.

China to Britain: Opium proceeds purchased Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain for British consumption

Britain to India: British manufactured goods exported to India, completing the triangle

The Impact on Indian Agriculture

Forced Cultivation: Indian peasants in Bengal and other regions were forced to grow opium instead of food crops. They received minimal payment—prices were set by the Company monopoly.

Food Insecurity: Diversion of agricultural land to opium cultivation reduced food production, contributing to famines and food insecurity.

No Benefits to India: All profits from opium went to the Company and British treasury. Indian cultivators received subsistence wages while their labor enriched Britain.

The Opium Wars: Fighting for Drug Trafficking

When China attempted to ban opium imports to protect its population from addiction, Britain fought two Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1860) to force China to accept British drug trafficking. Between 1839 and 1842, British-Indian forces fought a war with Imperial China that served the interests of opium smugglers. Their resulting victory opened up the lucrative Chinese trade to British merchants.

Remarkably, Britain used Indian soldiers and Indian-raised revenues to fight these wars—wars fought to protect British drug trafficking profits. India paid the cost of wars fought to force opium (grown in India) onto Chinese markets for British profit.

The $45 Trillion Drain: Quantifying the Theft

Drawing on nearly two centuries of detailed data on tax and trade, Patnaik calculated that Britain drained a total of nearly $45 trillion from India during the period 1765 to 1938. It’s a staggering sum. For perspective, $45 trillion is 17 times more than the total annual gross domestic product of the UK today.

How the $45 Trillion Was Extracted

This enormous sum represents multiple forms of extraction:

Revenue Collection: Land revenues, taxes, and tribute extracted from Indian taxpayers

Trade Exploitation: Forcing India to export raw materials at artificially low prices and import British manufactures at inflated prices

Home Charges: India paying for the entire cost of British administration, military, and debt service

Guaranteed Returns: India paying guaranteed profits to British investors even when their ventures lost money

Currency Manipulation: Exchange rate manipulation that increased the real value of wealth extracted

Capital Flight: Fortunes made by British officials and merchants in India, remitted to Britain

The Compound Interest Calculation

Patnaik’s calculation includes compound interest at a modest rate. This recognizes that wealth extracted in 1770 had 177 years to compound by 1947. If that wealth had remained in India and been invested in development, it would have generated returns for decades.

The compound interest calculation is not arbitrary—it represents the opportunity cost of extraction. Wealth drained from India couldn’t be invested in Indian agriculture, infrastructure, education, or industry. That lost investment opportunity compounds over time, explaining how £3 million annually extracted in 1765 becomes trillions by 1947.

Industrial Extraction Under the Crown (1900–1947)

Even after the Industrial Revolution matured, colonial extraction continued under new forms. The Crown administration institutionalized what the Company had pioneered — indirect economic control through fiscal policy, export quotas, and monetary manipulation.

The Home Charges system — payments India made to cover British administrative, military, and pension costs — drained roughly a third of India’s annual revenue right until independence. Indian industries remained stunted by deliberate neglect of heavy manufacturing, restrictive licensing, and currency policies that tied the rupee to the pound sterling, keeping Indian exports cheap and imports costly.

During both World Wars, India financed Britain’s defense: supplying troops, raw materials, and loans worth billions — only to face inflation, shortages, and yet another famine in 1943.

By 1947, the extraction model had evolved from direct plunder to structural dependency — India was industrially weakened, financially drained, and left to rebuild from ruins while Britain emerged with modern infrastructure, global influence, and accumulated capital born of Indian sweat.

Britain’s Industrial Revolution: Built on Indian Loot

The chronological and causal connection between Indian wealth extraction and British industrialization is undeniable:

Capital for Industrialization

The Industrial Revolution required enormous capital investment:

- Building factories and mills

- Purchasing machinery

- Developing infrastructure (canals, later railways)

- Financing research and development

- Providing working capital for enterprises

Where did this capital come from? Partially from domestic British savings, but significantly from wealth extracted from India:

- Bengal revenues providing Company profits

- Dividends to shareholders who invested in British industry

- Fortunes made by Company officials invested in British ventures

- Guaranteed returns on Indian investments funding British development

Raw Materials for British Industry

British industry required raw materials that India provided at artificially low prices:

- Cotton for textile mills

- Jute for burlap and rope manufacturing

- Indigo for dyes

- Tea, spices, and other agricultural products

- Iron and steel inputs

By controlling Indian production and prices, Britain ensured cheap raw materials for its industries—another form of subsidy extracting value from India to Britain.

Captive Markets for British Manufactures

As British industry developed, it needed markets. India provided a captive market:

- Population of 300+ million forced to buy British goods

- Tariffs preventing Indian competition

- Railways distributing British manufactures throughout India

- Destruction of Indian industries eliminating alternatives

India was forced to become both supplier of cheap raw materials and purchaser of expensive manufactures—the classic colonial exploitation pattern.

The Myth of British “Development” of India

British apologists claim that colonial rule “developed” India—building railways, establishing legal systems, providing modern administration. This myth collapses under examination:

Indians Paid for Everything

Every railway, telegraph line, and administrative building was paid for by Indian taxes. Britain invested nothing—it extracted revenues from India and spent a portion of those revenues on infrastructure serving British interests.

Infrastructure Served Extraction, Not Development

Railways transported raw materials to ports and British goods to interior—not connecting Indian cities for Indian benefit. Irrigation focused on cash crops for export rather than food security. Ports facilitated export of Indian resources rather than Indian trade.

Opportunity Costs Were Enormous

The revenues extracted by Britain could have funded:

- Universal primary education (instead of 12% literacy in 1947)

- Modern healthcare (instead of 32-year life expectancy)

- Industrial development (instead of deindustrialization)

- Agricultural improvement (instead of repeated famines)

- Infrastructure serving Indians (instead of infrastructure serving extraction)

Post-Independence Performance Proves the Point

Independent India, despite starting with massive poverty and underdevelopment, achieved in 75 years what Britain never attempted in 182 years:

- Universal education and 75%+ literacy

- Life expectancy increased to 70+ years

- Industrial development and export growth

- Food security and elimination of famines

- Infrastructure serving development, not extraction

If British rule had been “developmental,” India wouldn’t have been impoverished and underdeveloped in 1947.

The Legacy: Why This History Matters Today

Understanding how British prosperity was built on Indian impoverishment matters for several crucial reasons:

Challenging Western Exceptionalism

The myth of Western exceptionalism—that the West became prosperous through superior culture, harder work, or greater innovation—collapses when we understand that Western prosperity was substantially built on colonial extraction. Britain didn’t prosper because British culture was superior. Britain prospered because it systematically looted India for 182 years.

Understanding Global Inequality

Contemporary global inequality has deep historical roots. The wealth gap between the Global North and Global South was created and perpetuated through colonialism. Understanding this history is essential to understanding current inequality.

Reparations and Justice

If British prosperity was built on stolen Indian wealth, the question of reparations becomes unavoidable. The $45 trillion extracted from India represents wealth that rightfully belongs to India and Indians. Demands for reparations are not asking for charity—they’re asking for return of stolen property.

Educational Correction

British and Western education largely ignores or minimizes colonial extraction. Children learn about the Industrial Revolution as a story of innovation without learning it was funded by colonial loot. Correcting this historical amnesia is crucial for honest education.

Contemporary Colonial Attitudes

Britain’s refusal to acknowledge colonial crimes, return stolen artifacts, or consider reparations reveals continuing colonial attitudes. Understanding historical extraction helps identify persistent colonialism in contemporary British attitudes and policies.

Conclusion: The Greatest Economic Heist in History

Over 182 years (1765-1947), Britain extracted approximately $45 trillion from India—the greatest wealth transfer in human history. This wasn’t merely taxation or trade—it was systematic looting that destroyed Indian industries, impoverished Indian populations, killed tens of millions through famine, and transferred India’s wealth to fund Britain’s Industrial Revolution and global dominance.

The chronology is clear:

- 1765: Treaty of Allahabad begins systematic extraction

- 1770: First major famine kills 10 million—a direct result of Company policies

- 1780-1860: British industrialization accelerates using Indian wealth while India is systematically deindustrialized

- 1850s-1900s: Railways built with Indian money serve British extraction

- 1876-1943: Repeated famines kill 30-60 million through British policies

- 1947: India achieves independence impoverished and underdeveloped after nearly two centuries of systematic extraction

The causal relationship is undeniable: India’s impoverishment directly financed Britain’s enrichment. The poverty of India and the prosperity of Britain were two sides of the same coin—colonial extraction.

Britain likes to remember its empire with nostalgia—celebrating railways, rule of law, and the “civilizing mission.” This selective memory ignores:

- $45 trillion stolen through systematic extraction

- 30-60 million killed through policy-induced famines

- Systematic deindustrialization destroying millions of livelihoods

- Cultural treasures stolen and displayed as trophies

- Complete subordination of Indian welfare to British profit

The eight blogs in this series have documented:

- How merchants became rulers through exploitation of Indian divisions

- How the Treaty of Allahabad provided legal foundation for systematic extraction

- How British strategy exploited the divisions created by Islamic rule and prevented Hindu political consolidation

- How divide and rule made conquest possible despite overwhelming numerical inferiority

- How systematic economic drain transferred enormous wealth from India to Britain

- How physical looting of treasures accompanied economic extraction

- How policy-induced famines killed tens of millions

- How Indian wealth funded Britain’s Industrial Revolution while India was systematically impoverished

Together, these blogs provide comprehensive documentation of colonial exploitation—not for the purpose of nursing historical grievances, but for understanding historical truth. Only by acknowledging this history can we:

- Challenge myths of Western exceptionalism

- Understand the roots of contemporary global inequality

- Demand justice through reparations and return of stolen property

- Educate future generations honestly about colonialism

- Identify and resist contemporary forms of exploitation

The British looted and industrialized. They built their prosperity on India’s impoverishment. They created the modern world order through systematic exploitation. Understanding this history is not about dwelling on the past—it’s about honestly confronting it so we can build a more just future.

The series concludes, but the work of demanding historical justice, educating about colonial crimes, and challenging continuing colonial attitudes continues. That work belongs to all who care about truth, justice, and human dignity.

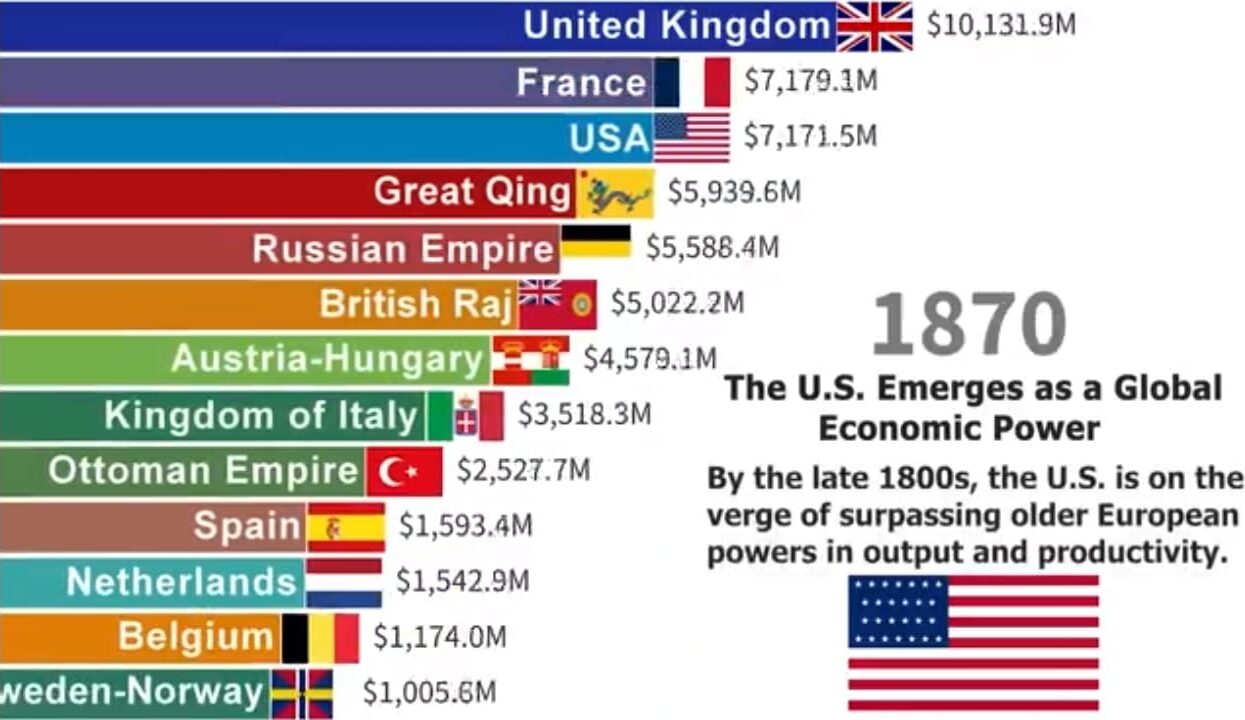

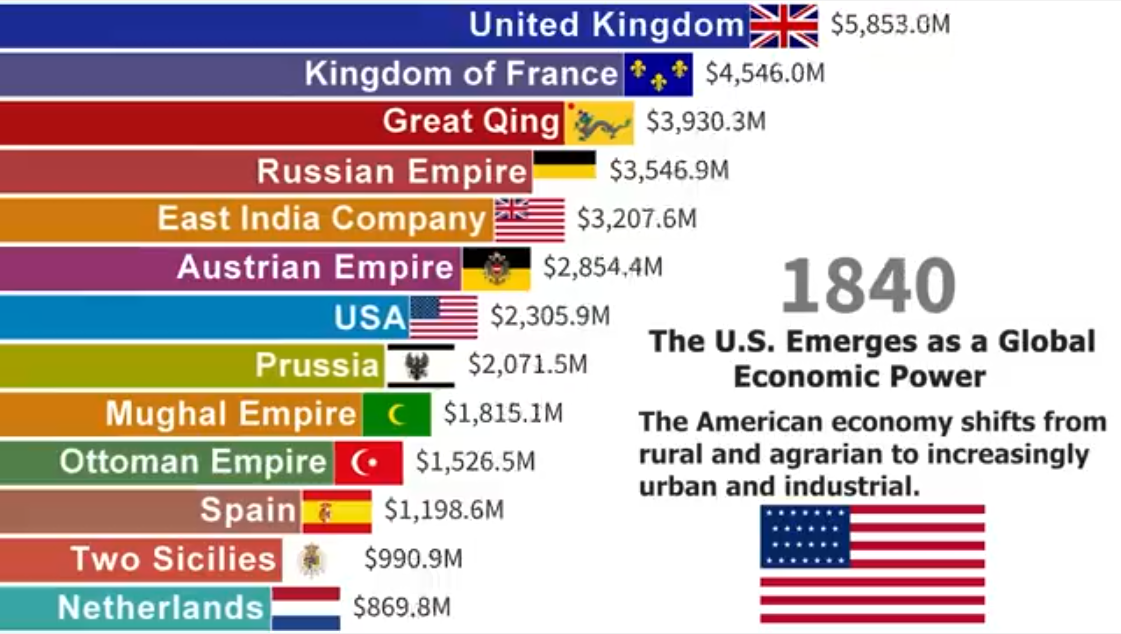

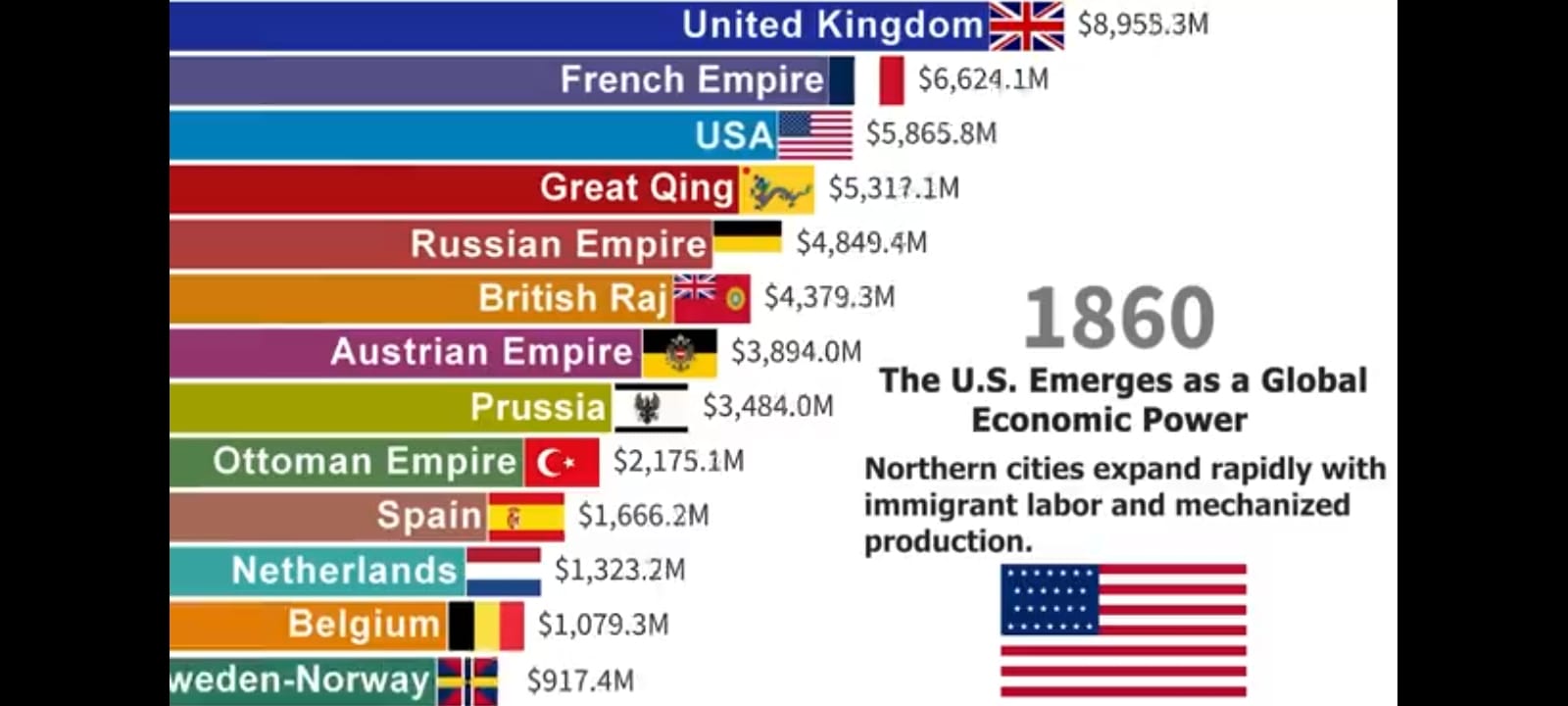

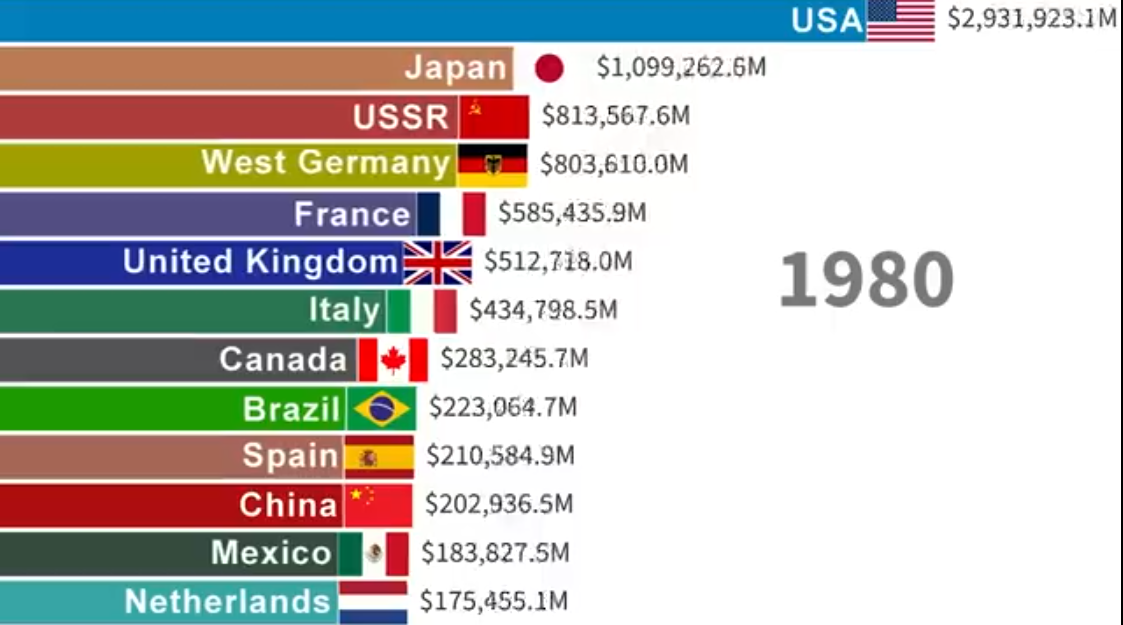

Each screenshot documents the economic transformation from Indian prosperity to British dominance, showing the direct causal relationship between India’s impoverishment and Britain’s enrichment.

Acknowledgment:

Data and historical context in this analysis draw from works by Utsa Patnaik, Angus Maddison, and official records of the Indian Famine Commission and India Office Papers.

🔹Call to Action

This concludes our eight-part series documenting how the East India Company and British Crown systematically exploited India for 182 years, extracting $45 trillion in wealth while killing tens of millions through famine and destroying India’s industries. Understanding this history is crucial for demanding justice and challenging continuing colonial attitudes.

Support our effort to document true history by:

- Sharing this series widely

- Contributing to this project

- Educating others about colonial crimes

- Demanding reparations and return of stolen artifacts

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Glossary of Terms

-

Treaty of Allahabad (1765): Agreement that granted the East India Company revenue rights (Diwani) over Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa—marking the start of formal British economic control.

-

Diwani Rights: The right to collect revenue and administer civil justice; granted to the East India Company by Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II after the Battle of Buxar.

-

East India Company: British trading corporation that evolved into a colonial authority ruling large parts of India until 1858, when the British Crown assumed control.

-

Utsa Patnaik: Indian economist known for calculating the estimated $45 trillion wealth drain from India to Britain between 1765 and 1938.

-

Angus Maddison: British economic historian who reconstructed historical GDP data, showing India’s economic decline and Britain’s rise during colonial rule.

-

Home Charges: Annual payments India was forced to make to Britain covering administrative costs, pensions, military expenses, and debt interest—key to the wealth drain.

-

Nabobs: British officials and merchants who amassed vast fortunes in India through exploitation and corruption, returning to Britain to invest in industry and politics.

-

Deindustrialization: The collapse of India’s traditional manufacturing and artisan sectors due to British trade policies, tariffs, and monopolies favoring British industries.

-

Opium Wars (1839–1860): Two wars fought by Britain against China to force the continuation of opium trade—funded and supplied through Indian cultivation under British monopoly.

-

Home Investment Guarantee: A system under which British investors received fixed returns from Indian revenues, ensuring profits regardless of Indian losses.

-

Wootz Steel: High-quality Indian steel used historically in Damascus swords; its production declined under British rule due to trade restrictions.

-

Famine Commission (1880, 1898): British-appointed bodies to study famine causes in India; often deflected blame from colonial policies despite overwhelming evidence of state-induced starvation.

-

Railway Guarantee System: Colonial financial policy ensuring British investors a 5% return from Indian taxes—turning Indian railways into instruments of extraction.

-

Jute and Indigo: Cash crops cultivated in India under British control for export; their forced production displaced food crops, worsening famines.

-

India Office Papers: Archival records in London documenting administrative and financial correspondence between British officials and the Indian government.

-

Colonial Drain Theory: Economic theory first articulated by Dadabhai Naoroji, explaining how wealth systematically flowed from India to Britain through trade, taxation, and remittance.

#BritishLoot #IndustrialRevolution #ColonialExploitation #IndiaWealthDrain #HinduinfoPedia

Follow us:

- English YouTube: Hinduostation – YouTube

- Hindi YouTube: Hinduinfopedia – YouTube

- X: https://x.com/HinduInfopedia

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hinduinfopedia/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Hinduinfopediaofficial

- Threads: https://www.threads.com/@hinduinfopedia

Previous Blogs of the Series

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-from-traders-to-rulers/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-treaty-of-allahabad-1765/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/east-india-company-vs-maratha-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/divide-and-rule-by-east-india-company/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/economy-in-british-raj-the-systematic-drain-of-indian-wealth/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-stole-indian-treasures-colonial-plunder-and-cultural-genocide/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/bengal-famine-and-british-genocides-how-colonial-policies-killed-millions/

Other related blogs and posts

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/british-rule-in-india-a-blessing-or-a-curse/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-education-system-and-its-legacy/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/islamic-influence-and-jazia-tax-in-india/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/battle-of-plassey-a-pivotal-turning-point-in-indian-history/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-arjan-dev-ji-architect-of-faith-and-martyrdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/maratha-empire-decline-consequences-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/guru-har-rai-a-legacy-of-compassion-and-strength/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indian-independence-and-mutiny-in-india-1857/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/indias-freedom-struggle-efforts-and-quit-india-movement-iii/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-tyrannical-monuments-a-legacy-of-despotism/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-ascent-governance-and-policy-dynamics/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/aurangzebs-early-life-prelude-to-power-of-criminal-empire/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/ahmad-shah-abdali-and-the-vadda-ghalughara-massacre/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/guru-tegh-bahadur-legacy-of-faith-and-freedom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-legacy-unraveling-controversies-of-mysore-tiger/

- https://hinduinfopedia.in/tipu-sultan-a-true-muslim/

- https://hinduinfopedia.com/gurukul-truths-of-hindu-wisdom/

- https://hinduinfopedia.org/gurukul-education-system-a-journey-through-time/

Leave a Reply