East India Company: From Traders to Rulers – The Complete Transformation

Part I: Study of East India Company and Foreign rule in Bharat

East India Company and The Mughal Court

This year marks 240 years since the East India Company Treaty of Allahabad with the Mughal court — a treaty that changed the fate of Bharat. On this occasion, we begin a series not to rewrite history, but to re-examine it. For too long, mainstream history books in Bharat have been manipulated texts, masking how 600 years of Muslim rule and 200 years of British rule together broke the nation’s sheen and growth.

The East India Company’s rise is one of history’s strangest transformations — a private trading firm that became the ruler of one of the world’s greatest civilizations, and in doing so accelerated the destruction of Sanatana culture. What began in 1600 with a royal charter from Queen Elizabeth I to buy spices and silk soon turned into a corporate empire that commanded armies, collected taxes, and dictated the destiny of millions. In just a century and a half, a handful of merchants evolved into masters of Bengal and beyond — not through sheer numbers, but through manipulation, alliances, and the cracks in India’s own political order.

Humble Beginnings of East India Company (1600-1700)

The East India Company was established with a simple mandate: to break the Dutch monopoly on the lucrative spice trade with the East Indies. Armed with royal charter and initial capital of £70,000, the Company’s first ships set sail for the Indian Ocean, seeking profitable trading opportunities in an already complex commercial landscape.

Unlike their European competitors, the early East India Company operations were remarkably modest. The Portuguese had already established coastal strongholds, while the Dutch East India Company dominated the Indonesian archipelago. The British, arriving later to this commercial competition, had to content themselves with securing trading rights from local rulers rather than establishing territorial control.

The Company’s initial strategy focused on establishing trading posts or “factories” along the Indian coast. Surat, established in 1612, became their first major foothold, followed by Madras in 1640, Bombay in 1668 (acquired through Catherine of Braganza’s dowry), and Calcutta in 1690. These settlements were primarily commercial centers, dependent on the goodwill of local rulers and focused entirely on trade rather than governance.

During this first century, the East India Company operated as a purely commercial entity. They purchased Indian textiles, spices, and precious goods using silver imported from the Americas, creating a profitable triangular trade system. The Company’s influence remained confined to their trading posts, with no ambitions of territorial expansion or political control.

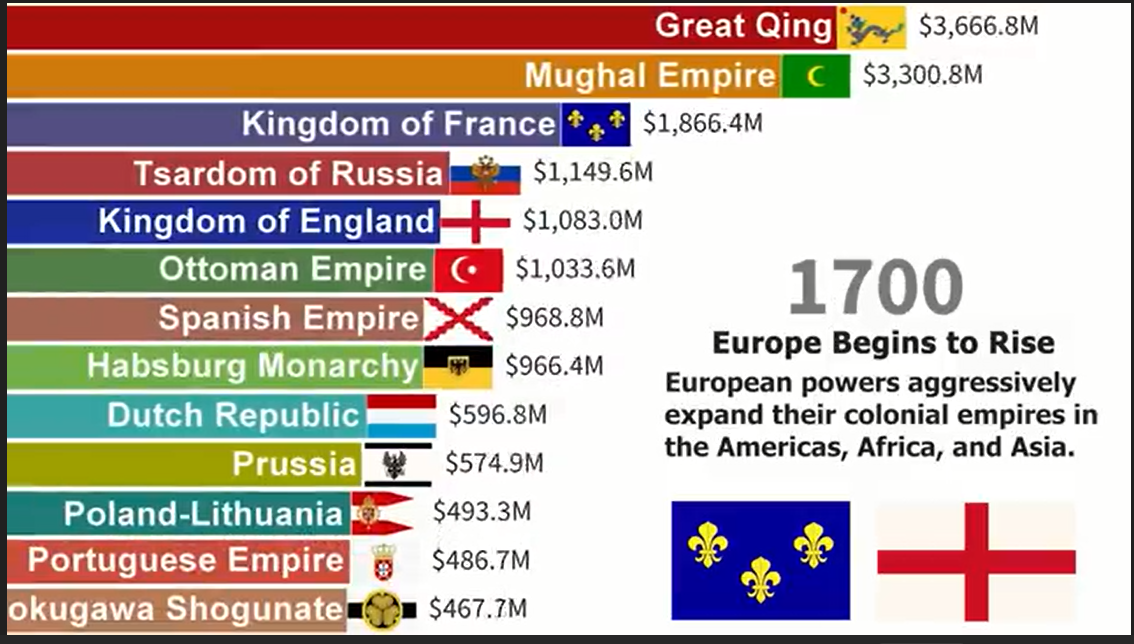

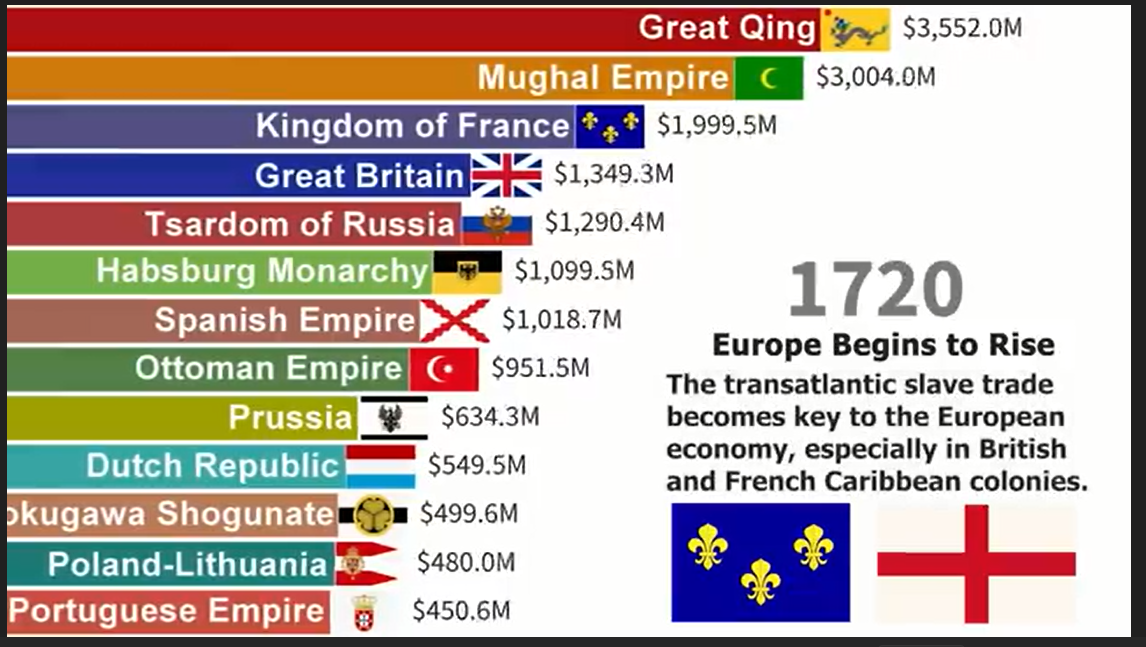

The Shifting Paradigm: From Commerce to Conquest (1700-1757)

The 18th century brought dramatic changes to the Indian political landscape that would fundamentally alter the East India Company’s role. The death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 marked the beginning of the Mughal Empire’s rapid decline—a decline directly caused by Veer Shivaji’s relentless resistance that had broken the seemingly invincible Islamic empire. Aurangzeb’s death wasn’t natural imperial aging; it was the result of decades of costly, failed campaigns against Hindu resistance that had drained the empire’s resources and morale.

This created a power vacuum that should have been naturally filled by the ascending Maratha Empire, which had already demonstrated its superiority over Islamic rule. However, European trading companies, particularly the East India Company, would cleverly exploit this transitional moment to insert themselves into India’s political landscape, fundamentally altering the natural trajectory toward Hindu political resurgence.

As central Mughal authority weakened following Aurangzeb’s tyrannical reign, the East India Company found itself increasingly drawn into local political disputes. What began as efforts to protect their commercial interests gradually evolved into military interventions and political alliances. The Company began recruiting and training Indian soldiers (sepoys) under European officers, creating a formidable military force that would prove decisive in future conflicts.

The transformation accelerated during the 1740s and 1750s, as European powers extended their continental conflicts to Indian soil. The Carnatic Wars between the British and French East India Companies demonstrated that European military techniques and discipline could defeat much larger Indian armies. These conflicts taught the British valuable lessons about Indian political fragmentation and the effectiveness of European military methods in the subcontinent.

Contemporary sources like the Siyar-ul-Mutakhkhirīn describe Siraj’s treatment of Hindu financiers as threatening, coercive, and laced with religious insult.

The Battle of Plassey (1757): The Watershed Moment

The Battle of Plassey on June 23, 1757, marked the definitive moment when the East India Company transformed from traders to territorial rulers. This pivotal encounter between Robert Clive’s forces and Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, would fundamentally alter the balance of power in India and interrupt the natural Hindu political renaissance that was already underway.

The battle itself was less a military contest than a political conspiracy. Clive’s army of approximately 3,000 men faced Siraj-ud-Daulah’s force of nearly 50,000 soldiers. However, the outcome was predetermined by the treachery of Mir Jafar, the Nawab’s military commander, who had secretly allied with the British in exchange for promises of being installed as the new Nawab.

The ease of this victory revealed crucial weaknesses in Islamic political and military structures that had been systematically exposed by decades of Hindu resistance. The Nawab’s army, though numerically superior, suffered from divided loyalties, corrupt leadership, and obsolete tactics—the same weaknesses that Shivaji had exploited to devastate Aurangzeb’s forces.

Modern historians such as William Dalrymple note how the Company turned these fractures into opportunities for conquest.

More importantly, the Battle of Plassey revealed how deeply fractured Bengal’s society had become by the mid-18th century. Sections of the Hindu population, particularly influential merchants, zamindars, and the powerful Jagat Seth banking family, shifted their allegiance away from Siraj-ud-Daulah. Their support for the Company was not born of admiration for foreign traders, but from resentment of the Nawab’s harsh fiscal demands, personal humiliations, and a climate of insecurity that echoed centuries of Islamic domination in Bengal. Contemporary sources such as the Siyar-ul-Mutakhkhirīn describe how Siraj’s treatment of Hindu financiers—threatening, coercive, and sometimes couched in religious insult—alienated those whose wealth could sustain or topple a ruler. Modern historians, including William Dalrymple, note how these fractures were exploited by the Company, which positioned itself as an alternative to a regime seen as both oppressive and unstable. In this way, Plassey was not just a clash of arms; it was the culmination of longstanding religious and political fissures in Bengal, crystallized in a moment when key Hindu elites calculated that their interests and their culture’s survival were safer under a profit-driven company than under yet another Nawab.

Plassey’s aftermath was equally significant. The East India Company did not simply defeat an enemy; it installed a puppet ruler and secured Bengal’s vast revenues. This moment marked the beginning of what historians describe as “Company rule” — a system where a commercial corporation exercised sovereign powers over Indian territories. In doing so, the Company rechanneled Bengal’s wealth for its own expansion and cut short the natural resurgence of Hindu political and cultural strength. The Mughal order, already weakened, collapsed like a pack of cards — not because the British were exceptionally powerful, but because centuries of extremist Islamic practices had eroded trust, created resentment, and left the empire brittle from within.

Plassey was not only a clash of arms but also a culmination of longstanding religious and political fissures in Bengal.

East India Company And The Battle of Buxar (1764)

Seven years after Plassey, the Battle of Buxar confirmed and expanded British dominance. This engagement saw the East India Company defeat a coalition of traditional powers: the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, the Nawab of Awadh, and the deposed Nawab of Bengal, Mir Qasim.

Buxar battle was more decisive than Plassey battle because it involved the formal Mughal authority rather than just regional rulers. The Company’s victory over this alliance effectively ended any meaningful resistance from traditional Indian powers in eastern India, clearing the path for what would become the Treaty of Allahabad. The battle demonstrated that the East India Company had evolved into a military power capable of defeating not just individual rulers but coordinated resistance from established Indian authorities.

The victory at Buxar battle also highlighted the Company’s superior military organization, training, and equipment as also its ability to exploitation of the weaknesses of its enemies. European drilling techniques, disciplined formations, and advanced artillery proved consistently effective against traditional Indian military methods that had been weakened by centuries of internal conflict and the systematic destruction of indigenous military traditions under Islamic rule. This shift at Buxar set the stage for a longer arc of resistance, which much later culminated in organized struggles such as the Quit India Movement, showing how the seeds of subjugation sown in the 18th century bore fruit in the 20th.

Plassey’s aftermath was equally significant. The East India Company did not simply defeat an enemy; it installed a puppet ruler and secured Bengal’s vast revenues. This moment marked the beginning of what historians describe as “Company rule” — a system where a commercial corporation exercised sovereign powers over Indian territories.

East India Company: From Financial Transaction to Empire Building

The East India Company’s transformation was fundamentally enabled by its growing financial resources extracted from territories that should have naturally fallen under Hindu rule. Control over Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa after 1765 provided the Company with enormous revenues that funded further expansion. Bengal alone generated approximately £3 million annually, making the Company financially independent of Britain and capable of funding its own military campaigns.

This financial transformation was crucial to understanding how a trading company became an imperial power by systematically preventing Hindu political consolidation. Unlike traditional conquests that drained royal treasuries, the East India Company’s expansion became self-financing. Each new territory conquered provided revenues to fund the next campaign, creating a cycle of profitable expansion that continued for decades while ensuring that no Hindu power could achieve the unity necessary to challenge British dominance.

The Company’s revenue system also demonstrated their sophisticated understanding of Indian administrative methods. Rather than imposing entirely foreign systems, they adapted existing Mughal revenue collection structures—unlike the Mughals, who often imposed heavy-handed and extractive policies—and frequently employed the same officials and procedures while redirecting the profits to Company coffers. These profits, however, should have naturally flowed to the emerging Hindu powers who had already proven their superiority over Islamic rule.

Comparison with European Competitors

The East India Company’s success stands in stark contrast to their European competitors. The Dutch East India Company, despite earlier success, remained focused on the Indonesian spice trade and never developed the territorial ambitions or military capabilities that characterized British expansion in India.

The French, through their Compagnie des Indes, posed the most serious challenge to British dominance. However, French efforts suffered from inconsistent support from Paris, divided leadership, and ultimately inferior financial resources. The decisive company victories in the Carnatic Wars eliminated France as a serious competitor for Indian dominance.

Portuguese influence, once dominant along the western coast, had long since declined to a few coastal enclaves. Their model of coastal fortresses and limited territorial control represented an earlier phase of European involvement in Asia that the British ultimately surpassed.

The Corporate Nature of East India Company Rule

One of the most remarkable aspects of this transformation was its corporate nature. The East India Company remained a joint-stock company even as it exercised sovereign powers. Shareholders in London received dividends from Indian revenues, while Company directors made decisions affecting millions of Indian subjects.

This corporate structure created unique dynamics in Indian governance. Company officials were motivated by profit rather than traditional imperial glory, leading to intensive revenue extraction and cost-cutting measures that often ignored local welfare. The Company’s accountability to shareholders rather than subjects created governance priorities that differed significantly from traditional monarchical rule.

East India Company: A Commercial Tool of Societal Destruction

By 1770, the East India Company had moved far beyond its original charter. From a few coastal factories, it now controlled territories larger than many European kingdoms, commanded disciplined armies, and extracted revenues that exceeded those of established monarchies. Its victories at Plassey and Buxar revealed not only the weakness of Indian rulers but also the deeper resentment Bengal’s Hindu majority held toward their Muslim overlords — resentment the Company skillfully exploited.

What made this transformation remarkable was not brute conquest but strategy: commercial wealth funding military expansion, Indian divisions turned into British opportunities, and corporate ambition reshaping an empire. Yet this was only the beginning. The real foundation of British dominion came in 1765, when the East India Company secured the Diwani of Bengal through the Treaty of Allahabad. That treaty turned merchants into tax-collectors and cemented Company rule — a turning point we will explore in the next blog of this series.

🔹Call to Action

Be a part of our exploration of the true history of Bharat and Sanatana culture by participating and contributing to the efforts by cash and kind.

As on the date of this post, Bharat is facing a new kind of imperialism — not through armies, but through economic, cultural, and ideological pressure from some of the world’s most powerful nations, who expect Bharat to conform to their narrative and interests. Unlike the past, where support was given to Mughals, and later to the Company and the British, this time let us not be divided. Let us unite and resist this new form of domination by embracing Swadeshi — choosing Made in India products and services this festival season. This is a battle not of swords, but of choices. Every rupee you spend is a vote for sovereignty.

Some of the items are listed in these posts. One can find more exhausted list of such products on line.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=741958019587362&set=a.741958082920689

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=112975937148466&id=105055061273887&set=a.105097474602979

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=112975937148466&id=105055061273887&set=a.105097474602979

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=134830901560630&id=115552010155186&set=a.121858612857859

🔗 Stay Connected

📺 YouTube Channels

English: Hinduostation – YouTube

Hindi: Hinduinfopedia – YouTube

📱 Follow us on Social Media

📚 Backup Blog Sites

👉 Read Blog 2: “East India Company Treaty of Allahabad 1765: The Legal Foundation of British Empire.”

Feature Image: Click here to view the image.

Leave a Reply